Deck 17: Governance and Regulation: Securities Law

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

فتح الحزمة

قم بالتسجيل لفتح البطاقات في هذه المجموعة!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/18

العب

ملء الشاشة (f)

Deck 17: Governance and Regulation: Securities Law

1

Steve Hindi is an animal rights activist who owns $5,000 in Pepsi stock. He discovered that Pepsi advertises in bull rings in Spain and Mexico, and he has attended annual shareholder meetings and put forward shareholder proposals to have the company halt the practice. His proposal did not pass, but he did not give up easily and started a website to increase pressure on the company. (See http://www.sharkonline.org for an article containing more details regarding this issue.)

Pepsi has withdrawn bullfighting ads in Mexico but continues with them in Spain. Mr. Hindi continues his quest. Should the proposal have been approved? Does Mr. Hindi run any risk with his website activism?

Pepsi has withdrawn bullfighting ads in Mexico but continues with them in Spain. Mr. Hindi continues his quest. Should the proposal have been approved? Does Mr. Hindi run any risk with his website activism?

Steve Hindi was an animal right activist and owns $5000 in Pepsi stock. He saw that Pepsi was involved in financing bullfighting for its advertising campaign. In the annual meeting of shareholders he forwarded the proposal to stop the practice or stop participating in such events. The Company stopped it in Mexico but continued it in Spain. Mr. Hindi did not stop opposing the company for halting the practice. He ran a website to show animal concern. Here Mr. Hindi was already an animal activist therefore he can have his website for the purpose. But if his website is meant to harm others or any organization then he may face regulations.

2

Which of the following rules does not have a limit on the size of the offering?

A) Rule 504

B) Rule 505

C) Rule 506

D) Regulation A

A) Rule 504

B) Rule 505

C) Rule 506

D) Regulation A

Rule 504: This rule is limited up to $1 Million USD. In case any company crosses that limit, it has to go for registration.

Rule 505: The rule offers an exemption up to $5, 00, 000 USD. A company crossing this mark has to go for registration.

Rule 506: This regulation offers an expanded qualifying amount for corporations to go for registration. It has no limits.

Regulation A: the rule offers an exemption up to $ 50, 00, 000 USD in case the companies meet the audit requirements.

In this question, the correct answer is option "C"; Regulation 506. It is because regulation offers an expanded qualifying amount for corporations to go for registration. It has no limits.

Therefore, the correct option is

Rule 505: The rule offers an exemption up to $5, 00, 000 USD. A company crossing this mark has to go for registration.

Rule 506: This regulation offers an expanded qualifying amount for corporations to go for registration. It has no limits.

Regulation A: the rule offers an exemption up to $ 50, 00, 000 USD in case the companies meet the audit requirements.

In this question, the correct answer is option "C"; Regulation 506. It is because regulation offers an expanded qualifying amount for corporations to go for registration. It has no limits.

Therefore, the correct option is

3

David Sokol, then-second in command at Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway company, bought $10 million in shares of Lubrizol, a company whose acquisition he would later recommend to Mr. Buffett. He then shepherded through the acquisition. When the SEC investigation of Mr. Sokol's advance stock purchase became public, Mr. Buffett said, "Neither Dave nor I feel his Lubrizol purchases were unlawful."

The audit committee for Berkshire Hathaway investigated and issued a report that condemned Mr. Sokol's conduct. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Buffett spoke at the annual shareholder meeting, "I don't think there's any question about the inexcusable part. He violated the code of ethics. He violated our insider trading rules. He violated the principles I lay out every two years." Did Mr. Sokol violate 10(b)?

The audit committee for Berkshire Hathaway investigated and issued a report that condemned Mr. Sokol's conduct. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Buffett spoke at the annual shareholder meeting, "I don't think there's any question about the inexcusable part. He violated the code of ethics. He violated our insider trading rules. He violated the principles I lay out every two years." Did Mr. Sokol violate 10(b)?

Section 10 (b) Violation:

A section 10 (b) violations occurs when a person buys a stock using information which is not commonly accessible to other people i.e. the general public. It is a punishable offence as it creates disparity.

As per the facts it is a clear violation of Section 10 (b) which condemns insider trading. The case is a violation because person D knows that the company L is for sale and he can recommend the acquisition of the company to person B.

He bought the shares of the company at a lower price and then suggested that the company should be acquired. Thus he was able to become a major shareholder in company B's new acquisition. This a violation of the insider trading laws because he was able to obtain inside information about a company which ordinary people cannot obtain and he used his power to buy the company itself, thus he utilized the insider information for personal interest.

Hence it can be concluded that person S has violate the law.

A section 10 (b) violations occurs when a person buys a stock using information which is not commonly accessible to other people i.e. the general public. It is a punishable offence as it creates disparity.

As per the facts it is a clear violation of Section 10 (b) which condemns insider trading. The case is a violation because person D knows that the company L is for sale and he can recommend the acquisition of the company to person B.

He bought the shares of the company at a lower price and then suggested that the company should be acquired. Thus he was able to become a major shareholder in company B's new acquisition. This a violation of the insider trading laws because he was able to obtain inside information about a company which ordinary people cannot obtain and he used his power to buy the company itself, thus he utilized the insider information for personal interest.

Hence it can be concluded that person S has violate the law.

4

Which of the following is permitted prior to the effective date of a registration statement?

A) Tombstone ad

B) Offering letter

C) Advance purchases

D) All of the above

A) Tombstone ad

B) Offering letter

C) Advance purchases

D) All of the above

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

5

Vincent Chiarella was employed as a printer in a financial printing firm that handled the printing for takeover bids. Although the firm names were left out of the financial materials and inserted at the last moment, Mr. Chiarella was able to deduce who was being taken over and by whom from other information in the reports being printed. Using this information, Mr. Chiarella was able to dabble in the stock market over a 14-month period for a net gain of $30,000. After an SEC investigation, he signed a consent decree that required him to return all of his profits to the sellers he purchased from during that 14-month period. He was then indicted for violation of 10(b) of the 1934 act and the SEC's Rule 10b-5. Did Mr. Chiarella violate 10b-5? [ Chiarella v United States , 445 U.S. 222 (1980)]

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

6

Who is liable for misrepresentations in the offering prospectus under the 1933 Securities Act?

A) Officers

B) Directors

C) Auditors

D) All of the above

A) Officers

B) Directors

C) Auditors

D) All of the above

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

7

How can a corporation violate Section 10(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act?

A) By not filing a prospectus

B) By issuing misleading press statements

C) By not filing a registration statement

D) Both a and b

A) By not filing a prospectus

B) By issuing misleading press statements

C) By not filing a registration statement

D) Both a and b

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

8

Section 16(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act applies to who?

A) Officer, directors, and 10 percent shareholders of 1934 Act companies

B) All employees of 1934 Act companies

C) Officers and directors of 1934 Act companies

D) All shareholders of 1934 Act companies

A) Officer, directors, and 10 percent shareholders of 1934 Act companies

B) All employees of 1934 Act companies

C) Officers and directors of 1934 Act companies

D) All shareholders of 1934 Act companies

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

9

Where can shareholder proposals for company action be found?

A) Prospectus

B) Registration statement

C) Offering

D) Proxy

A) Prospectus

B) Registration statement

C) Offering

D) Proxy

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

10

Escott v. BarChris Constr. Corp. 283 F. Supp. 643 (S.D.N.Y. 1968)

Bowling for Fraud: Right Up Our Alley

Facts

BarChris was a bowling alley company established in 1946. The bowling industry grew rapidly when automatic pin resetters went on the market in the mid-1950s. BarChris began a program of rapid expansion. BarChris used two methods of financing the construction of these alleys, both of which substantially drained the company's cash flow.

In 1960, BarChris's cash flow picture was troublesome, and it sold debentures. The debenture issue was registered with the SEC, approved, and sold. In spite of the cash boost from the sale, BarChris was still experiencing financial difficulties and declared bankruptcy in October 1962. The debenture holders were not paid their interest; BarChris defaulted.

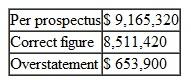

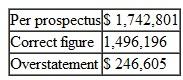

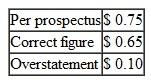

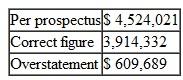

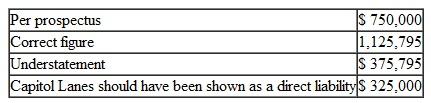

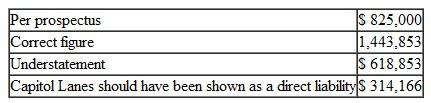

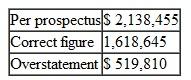

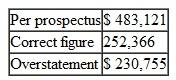

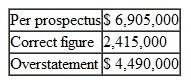

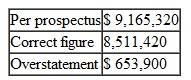

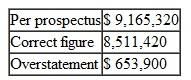

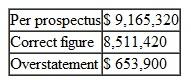

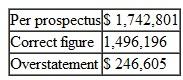

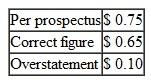

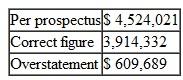

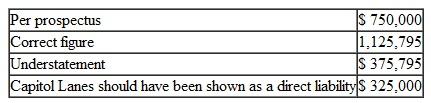

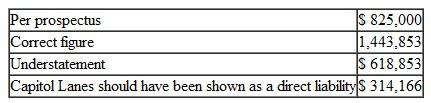

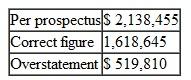

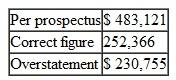

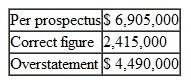

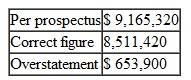

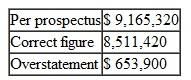

The purchasers of the BarChris debentures brought suit under Section 11 of the 1933 act. They claimed that the registration statement filed by BarChris contained false information and failed to disclose certain material information. The suit claimed that the audited financial statements prepared by a CPA firm were inaccurate and full of omissions. The following chart summarizes the problems with the financial statements submitted with the registration statements.

1. 1960 Earnings

(a) Sales

(b) Net Operating Income

(c) Earnings per Share

2. 1960 Balance Sheet

Current Assets

3. Contingent Liabilities as of December 31, 1960, on Alternative Method of Financing

4. Contingent Liabilities as of April 30, 1961

5. Earnings Figures for Quarter Ending March 31, 1961

(a) Sales

(b) Gross Profit

6. Backlog as of March 31, 1961

7. Failure to Disclose Officers' Loans Outstanding and

0

0

8. Failure to Disclose Use of Proceeds in Manner Not

1

1

9. Failure to Disclose Customers' Delinquencies in May 1961 and BarChris's Potential Liability with Respect

2

2

The federal district court reviewed each of the defendants' conduct, including officers, directors, attorneys, and the auditors (Peat, Marwick, Mitchell Co.3).

Judicial Opinion

McLEAN, District Judge

Vitolo and Pugliese. They were the founders of the business who stuck with it to the end. Vitolo and Pugliese are each men of limited education. It is not hard to believe that for them the prospectus was difficult reading, if indeed they read it at all.

But whether it was or not is irrelevant. The liability of a director who signs a registration statement does not depend upon whether or not he read it or, if he did, whether or not he understood what he was reading. All in all, the position of Vitolo and Pugliese is not significantly different, for present purposes, from Russo's. They could not have believed that the registration statement was wholly true and that no material facts had been omitted. And in any case, there is nothing to show that they made any investigation of anything which they may not have known about or understood. They have not proved their due diligence defenses.

Kircher. Kircher was treasurer of BarChris and its chief financial officer. He is a certified public accountant and an intelligent man. He was thoroughly familiar with BarChris's financial affairs. He knew of the customers' delinquency problems. He knew how the financing proceeds were to be applied and he saw to it that they were so applied. He arranged the officers' loans and he knew all the facts concerning them.

Kircher has not proved his due diligence defenses.

Birnbaum. Birnbaum was a young lawyer, admitted to the bar in 1957, who, after brief periods of employment by two different law firms and an equally brief period of practicing in his own firm, was employed by BarChris as house counsel and assistant secretary in October 1960. Unfortunately for him, he became secretary and director of BarChris on April 17, 1961, after the first version of the registration statement had been filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. He signed the later amendments, thereby becoming responsible for the accuracy of the prospectus in its final form.

It seems probable that Birnbaum did not know of many of the inaccuracies in the prospectus. He must, however, have appreciated some of them. In any case, he made no investigation and relied on the others to get it right. Having failed to make such an investigation, he did not have reasonable ground to believe that all these statements were true. Birnbaum has not established his due diligence defenses except as to the audited 1960 exhibits.

Auslander. Auslander was an "outside" director, i.e., one who was not an officer of BarChris. Auslander was elected a director on April 17, 1961. The registration statement in its original form had already been filed, of course without his signature. On May 10, 1961, he signed a signature page for the first amendment to the registration statement which was filed on May 11, 1961. This was a separate sheet without any document attached. Auslander did not know that it was a signature page for a registration statement. He vaguely understood that it was something "for the SEC."

Auslander never saw a copy of the registration statement in its final form. It is true that Auslander became a director on the eve of the financing. He had little opportunity to familiarize himself with the company's affairs.

Section 11 imposes liability in the first instance upon a director, no matter how new he is.

Peat, Marwick. Peat, Marwick's work was in general charge of a member of the firm, Cummings, and more immediately in charge of Peat, Marwick's manager, Logan. Most of the actual work was performed by a senior accountant, Berardi, who had junior assistants, one of whom was Kennedy.

Berardi was then about thirty years old. He was not yet a CPA. He had had no previous experience with the bowling industry. This was his first job as a senior accountant. He could hardly have been given a more difficult assignment.

After obtaining a little background information on BarChris by talking to Logan and reviewing Peat, Marwick's work papers on its 1959 audit, Berardi examined the results of test checks of BarChris's accounting procedures which one of the junior accountants had made, and he prepared an "internal control questionnaire" and an "audit program." Thereafter, for a few days subsequent to December 30, 1960, he inspected BarChris's inventories and examined certain alley construction. Finally, on January 13, 1961, he began his auditing work which he carried on substantially continuously until it was completed on February 24, 1961. Toward the close of the work, Logan reviewed it and made various comments and suggestions to Berardi.

Accountants should not be held to a standard higher than that recognized in their profession. I do not do so here. Berardi's review did not come up to that standard. He did not take some of the steps which Peat, Marwick's written program prescribed. He did not spend an adequate amount of time on a task of this magnitude. Most important of all, he was too easily satisfied with glib answers to his inquiries.

This is not to say that he should have made a complete audit. But there were enough danger signals in the materials which he did examine to require some further investigation on his part. Generally accepted accounting standards required such further investigation under these circumstances. It is not always sufficient merely to ask questions.

Case Questions

1. How much time transpired between the sale of the debentures and BarChris's bankruptcy?

2. Were all of the errors and omissions material?

3. Make a list of the shortcomings of the defendants in their due diligence.

Bowling for Fraud: Right Up Our Alley

Facts

BarChris was a bowling alley company established in 1946. The bowling industry grew rapidly when automatic pin resetters went on the market in the mid-1950s. BarChris began a program of rapid expansion. BarChris used two methods of financing the construction of these alleys, both of which substantially drained the company's cash flow.

In 1960, BarChris's cash flow picture was troublesome, and it sold debentures. The debenture issue was registered with the SEC, approved, and sold. In spite of the cash boost from the sale, BarChris was still experiencing financial difficulties and declared bankruptcy in October 1962. The debenture holders were not paid their interest; BarChris defaulted.

The purchasers of the BarChris debentures brought suit under Section 11 of the 1933 act. They claimed that the registration statement filed by BarChris contained false information and failed to disclose certain material information. The suit claimed that the audited financial statements prepared by a CPA firm were inaccurate and full of omissions. The following chart summarizes the problems with the financial statements submitted with the registration statements.

1. 1960 Earnings

(a) Sales

(b) Net Operating Income

(c) Earnings per Share

2. 1960 Balance Sheet

Current Assets

3. Contingent Liabilities as of December 31, 1960, on Alternative Method of Financing

4. Contingent Liabilities as of April 30, 1961

5. Earnings Figures for Quarter Ending March 31, 1961

(a) Sales

(b) Gross Profit

6. Backlog as of March 31, 1961

7. Failure to Disclose Officers' Loans Outstanding and

0

08. Failure to Disclose Use of Proceeds in Manner Not

1

19. Failure to Disclose Customers' Delinquencies in May 1961 and BarChris's Potential Liability with Respect

2

2The federal district court reviewed each of the defendants' conduct, including officers, directors, attorneys, and the auditors (Peat, Marwick, Mitchell Co.3).

Judicial Opinion

McLEAN, District Judge

Vitolo and Pugliese. They were the founders of the business who stuck with it to the end. Vitolo and Pugliese are each men of limited education. It is not hard to believe that for them the prospectus was difficult reading, if indeed they read it at all.

But whether it was or not is irrelevant. The liability of a director who signs a registration statement does not depend upon whether or not he read it or, if he did, whether or not he understood what he was reading. All in all, the position of Vitolo and Pugliese is not significantly different, for present purposes, from Russo's. They could not have believed that the registration statement was wholly true and that no material facts had been omitted. And in any case, there is nothing to show that they made any investigation of anything which they may not have known about or understood. They have not proved their due diligence defenses.

Kircher. Kircher was treasurer of BarChris and its chief financial officer. He is a certified public accountant and an intelligent man. He was thoroughly familiar with BarChris's financial affairs. He knew of the customers' delinquency problems. He knew how the financing proceeds were to be applied and he saw to it that they were so applied. He arranged the officers' loans and he knew all the facts concerning them.

Kircher has not proved his due diligence defenses.

Birnbaum. Birnbaum was a young lawyer, admitted to the bar in 1957, who, after brief periods of employment by two different law firms and an equally brief period of practicing in his own firm, was employed by BarChris as house counsel and assistant secretary in October 1960. Unfortunately for him, he became secretary and director of BarChris on April 17, 1961, after the first version of the registration statement had been filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. He signed the later amendments, thereby becoming responsible for the accuracy of the prospectus in its final form.

It seems probable that Birnbaum did not know of many of the inaccuracies in the prospectus. He must, however, have appreciated some of them. In any case, he made no investigation and relied on the others to get it right. Having failed to make such an investigation, he did not have reasonable ground to believe that all these statements were true. Birnbaum has not established his due diligence defenses except as to the audited 1960 exhibits.

Auslander. Auslander was an "outside" director, i.e., one who was not an officer of BarChris. Auslander was elected a director on April 17, 1961. The registration statement in its original form had already been filed, of course without his signature. On May 10, 1961, he signed a signature page for the first amendment to the registration statement which was filed on May 11, 1961. This was a separate sheet without any document attached. Auslander did not know that it was a signature page for a registration statement. He vaguely understood that it was something "for the SEC."

Auslander never saw a copy of the registration statement in its final form. It is true that Auslander became a director on the eve of the financing. He had little opportunity to familiarize himself with the company's affairs.

Section 11 imposes liability in the first instance upon a director, no matter how new he is.

Peat, Marwick. Peat, Marwick's work was in general charge of a member of the firm, Cummings, and more immediately in charge of Peat, Marwick's manager, Logan. Most of the actual work was performed by a senior accountant, Berardi, who had junior assistants, one of whom was Kennedy.

Berardi was then about thirty years old. He was not yet a CPA. He had had no previous experience with the bowling industry. This was his first job as a senior accountant. He could hardly have been given a more difficult assignment.

After obtaining a little background information on BarChris by talking to Logan and reviewing Peat, Marwick's work papers on its 1959 audit, Berardi examined the results of test checks of BarChris's accounting procedures which one of the junior accountants had made, and he prepared an "internal control questionnaire" and an "audit program." Thereafter, for a few days subsequent to December 30, 1960, he inspected BarChris's inventories and examined certain alley construction. Finally, on January 13, 1961, he began his auditing work which he carried on substantially continuously until it was completed on February 24, 1961. Toward the close of the work, Logan reviewed it and made various comments and suggestions to Berardi.

Accountants should not be held to a standard higher than that recognized in their profession. I do not do so here. Berardi's review did not come up to that standard. He did not take some of the steps which Peat, Marwick's written program prescribed. He did not spend an adequate amount of time on a task of this magnitude. Most important of all, he was too easily satisfied with glib answers to his inquiries.

This is not to say that he should have made a complete audit. But there were enough danger signals in the materials which he did examine to require some further investigation on his part. Generally accepted accounting standards required such further investigation under these circumstances. It is not always sufficient merely to ask questions.

Case Questions

1. How much time transpired between the sale of the debentures and BarChris's bankruptcy?

2. Were all of the errors and omissions material?

3. Make a list of the shortcomings of the defendants in their due diligence.

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

11

Which of the following is a requirement under SOX?

A) Rotation of the audit firm every five years

B) Shareholder vote on CEO pay

C) Rotation of the audit partner every five years

D) Internal control certification by management

A) Rotation of the audit firm every five years

B) Shareholder vote on CEO pay

C) Rotation of the audit partner every five years

D) Internal control certification by management

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

12

Charles Edwards was the chairman, chief executive officer, and sole shareholder of ETS Payphones, Inc. ETS sold payphones packaged with a site lease, a five-year leaseback and management agreement, and a buyback agreement. The purchase price for the payphone packages was approximately $7,000. Under the leaseback and management agreement, purchasers received $82 per month, a 14 percent annual return.

Purchasers were not involved in the day-to-day operation of the payphones they owned. ETS selected the site for the phones, installed the equipment, arranged for connection and long-distance service, collected coin revenues, and maintained and repaired the phones. The payphones did not generate enough revenue for ETS to make the payments required by the leaseback agreements, so the company depended on funds from new investors to meet its obligations.

In September 2000, ETS filed for bankruptcy. The SEC brought suit against Edwards and ETS for failure to register securities prior to sale. The district court concluded the arrangement was an "investment contract" subject to the securities laws. The Court of Appeals reversed the lower court. Which court is correct? Did the sale of securities take place? [ SEC v. Edwards , 540 U.S. 389 (2004).]

Purchasers were not involved in the day-to-day operation of the payphones they owned. ETS selected the site for the phones, installed the equipment, arranged for connection and long-distance service, collected coin revenues, and maintained and repaired the phones. The payphones did not generate enough revenue for ETS to make the payments required by the leaseback agreements, so the company depended on funds from new investors to meet its obligations.

In September 2000, ETS filed for bankruptcy. The SEC brought suit against Edwards and ETS for failure to register securities prior to sale. The district court concluded the arrangement was an "investment contract" subject to the securities laws. The Court of Appeals reversed the lower court. Which court is correct? Did the sale of securities take place? [ SEC v. Edwards , 540 U.S. 389 (2004).]

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

13

To which of the following is due diligence a defense?

A) Section 11 of the 1933 Securities Act

B) 10(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act

C) 16(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act

D) Regulation D

A) Section 11 of the 1933 Securities Act

B) 10(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act

C) 16(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act

D) Regulation D

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

14

Which of the following would be exempt from 1933 Securities Act registration?

A) Limited partnership interests

B) Sale of securities in a C corporation

C) General partnership interests

D) All of the above

A) Limited partnership interests

B) Sale of securities in a C corporation

C) General partnership interests

D) All of the above

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

15

Siracusano v. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. 131 S.Ct. 1309 (2011)

Missing Disclosures by a Nose

Facts

Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. ("Matrixx") is a pharmaceutical company that sells Zicam through its wholly-owned subsidiary, Zicam, LLC. One of its products, responsible for 70% of its sales, is Zicam Cold Remedy, a homeopathic product marketed as stopping or minimizing cold symptoms.

In December 1999, Matrixx began to get questions from physicians whose patients were developing anosmia (loss of the sense of smell). Researchers at medical facilities contacted Matrixx in 2002 to offer access to studies showing that zinc sulfate (Zicam also had zinc in it) was linked to anosmia.

Matrixx's SEC filings did not discuss these inquiries and studies. In fact, on October 22, 2003, Matrixx issued an optimistic press release that the third quarter of 2003 had increased revenues by 163% over the third quarter of 2002. On an October 23, 2003, earnings conference call, executives for Matrixx expressed their "optimis[m] about the future." At one point during the call, Zicam executives were asked to "make any comment on the litigation MTXX or its officers are involved in, or whether or not there is any SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission] investigation." They replied that there was no litigation and that they were not aware of any SEC investigation. In truth, a lawsuit alleging that Zicam caused anosmia had already been filed at this time.

By January 30, 2004, the FDA was investigating whether Zicam may be causing some users to lose their sense of smell. Matrixx's stock then declined, "falling from $13.55 per share on January 30, 2004 to $11.97 per share on February 2, 2004."

NECA-IBEW Pension Fund and James Siracusano (plaintiffs/appellants) brought a class action suit against Matrixx and three Matrixx executives (Appellees) alleging a violation of 10(b) by their failure to disclose material information regarding problems with Zicam. The district court granted Matrixx's motion to dismiss the complaint. The court of appeals reversed. The shareholders appealed.

Judicial Opinion

SOTOMAYOR, Justice

To prevail on a § 10(b) claim, a plaintiff must show that the defendant made a statement that was "misleading as to a material fact."

Matrixx urges us to adopt a bright-line rule that reports of adverse events associated with a pharmaceutical company's products cannot be material absent a sufficient number of such reports to establish a statistically significant risk that the product is in fact causing the events. Absent statistical significance, Matrixx argues, adverse event reports provide only "anecdotal" evidence that "the user of a drug experienced an adverse event at some point during or following the use of that drug." Accordingly, it contends, reasonable investors would not consider such reports relevant unless they are statistically significant because only then do they "reflect a scientifically reliable basis for inferring a potential causal link between product use and the adverse event."

A lack of statistically significant data does not mean that medical experts have no reliable basis for inferring a causal link between a drug and adverse events. As Matrixx itself concedes, medical experts rely on other evidence to establish an inference of causation.

The FDA similarly does not limit the evidence it considers for purposes of assessing causation and taking regulatory action to statistically significant data. For example, the FDA requires manufacturers of overthe- counter drugs to revise their labeling "to include a warning as soon as there is reasonable evidence of an association of a serious hazard with a drug; a causal relationship need not have been proved."

This case proves the point. In 2009, the FDA issued a warning letter to Matrixx stating that "[a] significant and growing body of evidence substantiates that the Zicam Cold Remedy intranasal products may pose a serious risk to consumers who use them." The letter cited as evidence 130 reports of anosmia the FDA had received, the fact that the FDA had received few reports of anosmia associated with other intranasal cold remedies, and "evidence in the published scientific literature that various salts of zinc can damage olfactory function in animals and humans." It did not cite statistically significant data. Given that medical professionals and regulators act on the basis of evidence of causation that is not statistically significant, it stands to reason that in certain cases reasonable investors would as well.

Medical experts revealed a plausible causal relationship between Zicam Cold Remedy and anosmia. Consumers likely would have viewed the risk associated with Zicam (possible loss of smell) as substantially outweighing the benefit of using the product (alleviating cold symptoms), particularly in light of the existence of many alternative products on the market. [T]he complaint alleges facts suggesting a significant risk to the commercial viability of Matrixx's leading product. It is substantially likely that a reasonable investor would have viewed this information "'as having significantly altered the "total mix" of information made available.'"

Matrixx elected not to disclose the reports of adverse events not because it believed they were meaningless but because it understood their likely effect on the market. [A] reasonable person would deem the inference that Matrixx acted with deliberate recklessness (or even intent). We conclude, in agreement with the Court of Appeals, that respondents have adequately pleaded [materiality and] scienter.

Affirmed.

Case Questions

1. Based on this decision, if you had been the executives at Matrixx, what would you have disclosed and when would you have disclosed it?

2. Why is it relevant that consumers would be affected by the studies, whether significant or not?

3. By 2009, the FDA required that Zicam be removed from stores and warned consumers about the risk of losing their sense of smell. What happens to the company as a result? What will be the impact on Matrixx investors? What will their damages be?

Missing Disclosures by a Nose

Facts

Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. ("Matrixx") is a pharmaceutical company that sells Zicam through its wholly-owned subsidiary, Zicam, LLC. One of its products, responsible for 70% of its sales, is Zicam Cold Remedy, a homeopathic product marketed as stopping or minimizing cold symptoms.

In December 1999, Matrixx began to get questions from physicians whose patients were developing anosmia (loss of the sense of smell). Researchers at medical facilities contacted Matrixx in 2002 to offer access to studies showing that zinc sulfate (Zicam also had zinc in it) was linked to anosmia.

Matrixx's SEC filings did not discuss these inquiries and studies. In fact, on October 22, 2003, Matrixx issued an optimistic press release that the third quarter of 2003 had increased revenues by 163% over the third quarter of 2002. On an October 23, 2003, earnings conference call, executives for Matrixx expressed their "optimis[m] about the future." At one point during the call, Zicam executives were asked to "make any comment on the litigation MTXX or its officers are involved in, or whether or not there is any SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission] investigation." They replied that there was no litigation and that they were not aware of any SEC investigation. In truth, a lawsuit alleging that Zicam caused anosmia had already been filed at this time.

By January 30, 2004, the FDA was investigating whether Zicam may be causing some users to lose their sense of smell. Matrixx's stock then declined, "falling from $13.55 per share on January 30, 2004 to $11.97 per share on February 2, 2004."

NECA-IBEW Pension Fund and James Siracusano (plaintiffs/appellants) brought a class action suit against Matrixx and three Matrixx executives (Appellees) alleging a violation of 10(b) by their failure to disclose material information regarding problems with Zicam. The district court granted Matrixx's motion to dismiss the complaint. The court of appeals reversed. The shareholders appealed.

Judicial Opinion

SOTOMAYOR, Justice

To prevail on a § 10(b) claim, a plaintiff must show that the defendant made a statement that was "misleading as to a material fact."

Matrixx urges us to adopt a bright-line rule that reports of adverse events associated with a pharmaceutical company's products cannot be material absent a sufficient number of such reports to establish a statistically significant risk that the product is in fact causing the events. Absent statistical significance, Matrixx argues, adverse event reports provide only "anecdotal" evidence that "the user of a drug experienced an adverse event at some point during or following the use of that drug." Accordingly, it contends, reasonable investors would not consider such reports relevant unless they are statistically significant because only then do they "reflect a scientifically reliable basis for inferring a potential causal link between product use and the adverse event."

A lack of statistically significant data does not mean that medical experts have no reliable basis for inferring a causal link between a drug and adverse events. As Matrixx itself concedes, medical experts rely on other evidence to establish an inference of causation.

The FDA similarly does not limit the evidence it considers for purposes of assessing causation and taking regulatory action to statistically significant data. For example, the FDA requires manufacturers of overthe- counter drugs to revise their labeling "to include a warning as soon as there is reasonable evidence of an association of a serious hazard with a drug; a causal relationship need not have been proved."

This case proves the point. In 2009, the FDA issued a warning letter to Matrixx stating that "[a] significant and growing body of evidence substantiates that the Zicam Cold Remedy intranasal products may pose a serious risk to consumers who use them." The letter cited as evidence 130 reports of anosmia the FDA had received, the fact that the FDA had received few reports of anosmia associated with other intranasal cold remedies, and "evidence in the published scientific literature that various salts of zinc can damage olfactory function in animals and humans." It did not cite statistically significant data. Given that medical professionals and regulators act on the basis of evidence of causation that is not statistically significant, it stands to reason that in certain cases reasonable investors would as well.

Medical experts revealed a plausible causal relationship between Zicam Cold Remedy and anosmia. Consumers likely would have viewed the risk associated with Zicam (possible loss of smell) as substantially outweighing the benefit of using the product (alleviating cold symptoms), particularly in light of the existence of many alternative products on the market. [T]he complaint alleges facts suggesting a significant risk to the commercial viability of Matrixx's leading product. It is substantially likely that a reasonable investor would have viewed this information "'as having significantly altered the "total mix" of information made available.'"

Matrixx elected not to disclose the reports of adverse events not because it believed they were meaningless but because it understood their likely effect on the market. [A] reasonable person would deem the inference that Matrixx acted with deliberate recklessness (or even intent). We conclude, in agreement with the Court of Appeals, that respondents have adequately pleaded [materiality and] scienter.

Affirmed.

Case Questions

1. Based on this decision, if you had been the executives at Matrixx, what would you have disclosed and when would you have disclosed it?

2. Why is it relevant that consumers would be affected by the studies, whether significant or not?

3. By 2009, the FDA required that Zicam be removed from stores and warned consumers about the risk of losing their sense of smell. What happens to the company as a result? What will be the impact on Matrixx investors? What will their damages be?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

16

In August 1994, Mervyn Cooper, a psychotherapist, was providing marriage counseling to a Lockheed executive. The executive had been assigned to conduct the due diligence (review of the accuracy of the books and records) of Martin Marietta, a company with which Lockheed was going to merge.

At his August 22, 1994, session with Mr. Cooper, the executive revealed to him the pending, but nonpublic, merger. Following his session with the executive, Mr. Cooper contacted a friend, Kenneth Rottenberg, and told him about the pending merger. They agreed that Mr. Rottenberg would open a brokerage account so they could buy Lockheed call options and common stocks and then share in the profits.

When Mr. Rottenberg went to some brokerage offices to set up an account, he was warned by a broker about the risks of call options. Mr. Rottenberg told the broker that Lockheed would announce a major business combination shortly and that he would not lose his money.

Did Mr. Rottenberg and Mr. Cooper violate Section 10(b)? What about the broker? [ SEC v Mervyn Cooper and Kenneth E. Rottenberg, No. 95-8535 (C.D. Cal. 1995)]

At his August 22, 1994, session with Mr. Cooper, the executive revealed to him the pending, but nonpublic, merger. Following his session with the executive, Mr. Cooper contacted a friend, Kenneth Rottenberg, and told him about the pending merger. They agreed that Mr. Rottenberg would open a brokerage account so they could buy Lockheed call options and common stocks and then share in the profits.

When Mr. Rottenberg went to some brokerage offices to set up an account, he was warned by a broker about the risks of call options. Mr. Rottenberg told the broker that Lockheed would announce a major business combination shortly and that he would not lose his money.

Did Mr. Rottenberg and Mr. Cooper violate Section 10(b)? What about the broker? [ SEC v Mervyn Cooper and Kenneth E. Rottenberg, No. 95-8535 (C.D. Cal. 1995)]

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

17

The purpose of Regulation D is what?

A) To eliminate registration for intrastate offerings

B) To require registration for all offerings over $5,000,000

C) To eliminate registration for securities transferred as part of a Chapter 11 bankruptcy

D) None of the above

A) To eliminate registration for intrastate offerings

B) To require registration for all offerings over $5,000,000

C) To eliminate registration for securities transferred as part of a Chapter 11 bankruptcy

D) None of the above

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

18

United States v. O'Hagan 521 U.S. 657 (1997)

Pillsbury Dough Boy: The Lawyer/Insider Who Cashed In

Facts

James Herman O'Hagan (respondent) was a partner in the law firm of Dorsey Whitney in Minneapolis, Minnesota. In July 1988, Grand Metropolitan PLC (Grand Met), a company based in London, retained Dorsey Whitney as local counsel to represent it in a potential tender offer for common stock of Pillsbury Company (based in Minneapolis).

Mr. O'Hagan did not work on the Grand Met matter, so on August 18, 1988, he began purchasing call options for Pillsbury stock. Each option gave him the right to purchase 100 shares of Pillsbury stock. By the end of September, Mr. O'Hagan owned more than 2,500 Pillsbury options. Also in September, Mr. O'Hagan purchased 5,000 shares of Pillsbury stock at $39 per share.

Grand Met announced its tender offer in October, and Pillsbury stock rose to $60 per share. Mr. O'Hagan sold his call options and made a profit of $4.3 million. The SEC indicted Mr. O'Hagan on 57 counts of illegal trading on inside information and other charges. Mr. O'Hagan was convicted by a jury on all 57 counts and sentenced to 41 months in prison. A divided Court of Appeals reversed the conviction, and the SEC appealed.

Judicial Opinion

GINSBURG, Justice

The "misappropriation theory" holds that a person commits fraud "in connection with" a securities transaction, and thereby violates § 10(b) and Rule 10b-5, when he misappropriates confidential information for securities trading purposes, in breach of a duty owed to the source of the information. Under this theory, a fiduciary's undisclosed, [S]elf-serving use of a principal's information to purchase or sell securities, in breach of a duty of loyalty and confidentiality, defrauds the principal of the exclusive use of that information.

We observe, first, that misappropriators, as the Government describes them, deal in deception. A fiduciary who "[pretends] loyalty to the principal while secretly converting the principal's information for personal gain" "dupes" or defrauds the principal.

An investor's informational disadvantage visà- vis a misappropriator with material, nonpublic information stems from contrivance, not luck; it is a disadvantage that cannot be overcome with research or skill.

In sum, considering the inhibiting impact on market participation of trading on misappropriated information, and the congressional purposes underlying § 10(b), it makes scant sense to hold a lawyer like O'Hagan a § 10(b) violator if he works for a law firm representing the target of a tender offer, but not if he works for a law firm representing the bidder.

[W]e emphasize … two sturdy safeguards Congress has provided regarding scienter. To establish a criminal violation of Rule 10b-5, the Government must prove that a person "willfully" violated the provision. In addition, the statute's "requirement of the presence of culpable intent as a necessary element of the offense does much to destroy any force in the argument that application of the [statute]" in circumstances such as O'Hagan's is unjust.

Reversed.

Case Questions

1. What does the court say the misappropriation theory is?

2. Did Mr. O'Hagan make money from non-public information?

3. Could others have done research and obtained the same information Mr. O'Hagan had?

Pillsbury Dough Boy: The Lawyer/Insider Who Cashed In

Facts

James Herman O'Hagan (respondent) was a partner in the law firm of Dorsey Whitney in Minneapolis, Minnesota. In July 1988, Grand Metropolitan PLC (Grand Met), a company based in London, retained Dorsey Whitney as local counsel to represent it in a potential tender offer for common stock of Pillsbury Company (based in Minneapolis).

Mr. O'Hagan did not work on the Grand Met matter, so on August 18, 1988, he began purchasing call options for Pillsbury stock. Each option gave him the right to purchase 100 shares of Pillsbury stock. By the end of September, Mr. O'Hagan owned more than 2,500 Pillsbury options. Also in September, Mr. O'Hagan purchased 5,000 shares of Pillsbury stock at $39 per share.

Grand Met announced its tender offer in October, and Pillsbury stock rose to $60 per share. Mr. O'Hagan sold his call options and made a profit of $4.3 million. The SEC indicted Mr. O'Hagan on 57 counts of illegal trading on inside information and other charges. Mr. O'Hagan was convicted by a jury on all 57 counts and sentenced to 41 months in prison. A divided Court of Appeals reversed the conviction, and the SEC appealed.

Judicial Opinion

GINSBURG, Justice

The "misappropriation theory" holds that a person commits fraud "in connection with" a securities transaction, and thereby violates § 10(b) and Rule 10b-5, when he misappropriates confidential information for securities trading purposes, in breach of a duty owed to the source of the information. Under this theory, a fiduciary's undisclosed, [S]elf-serving use of a principal's information to purchase or sell securities, in breach of a duty of loyalty and confidentiality, defrauds the principal of the exclusive use of that information.

We observe, first, that misappropriators, as the Government describes them, deal in deception. A fiduciary who "[pretends] loyalty to the principal while secretly converting the principal's information for personal gain" "dupes" or defrauds the principal.

An investor's informational disadvantage visà- vis a misappropriator with material, nonpublic information stems from contrivance, not luck; it is a disadvantage that cannot be overcome with research or skill.

In sum, considering the inhibiting impact on market participation of trading on misappropriated information, and the congressional purposes underlying § 10(b), it makes scant sense to hold a lawyer like O'Hagan a § 10(b) violator if he works for a law firm representing the target of a tender offer, but not if he works for a law firm representing the bidder.

[W]e emphasize … two sturdy safeguards Congress has provided regarding scienter. To establish a criminal violation of Rule 10b-5, the Government must prove that a person "willfully" violated the provision. In addition, the statute's "requirement of the presence of culpable intent as a necessary element of the offense does much to destroy any force in the argument that application of the [statute]" in circumstances such as O'Hagan's is unjust.

Reversed.

Case Questions

1. What does the court say the misappropriation theory is?

2. Did Mr. O'Hagan make money from non-public information?

3. Could others have done research and obtained the same information Mr. O'Hagan had?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 18 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck