Deck 5: Fraud in Financial Statements and Auditor Responsibilities

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

فتح الحزمة

قم بالتسجيل لفتح البطاقات في هذه المجموعة!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/30

العب

ملء الشاشة (f)

Deck 5: Fraud in Financial Statements and Auditor Responsibilities

1

Computer Associates

Computer Associates (CA) is a business consulting and software development company that designs, markets, and licenses computer software products that allow businesses to run and manage critical aspects of their information technology efficiently. CA's stock trades on the NYSE and is registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Exchange Act, 15 U.S.C. §78l(b).

Between about the fourth quarter of fiscal year (FY) 1998 through the second quarter of FY2001, CA engaged in a widespread practice that allowed for the premature recognition of revenue from software licensing agreements. CA personnel recorded, into the just-elapsed fiscal quarter, revenue from software contracts that were not finalized and signed by both CA and its customers until days or weeks after that quarter ended. The reported revenue was improper because it violated GAAP, which required that license agreements be fully executed by both CA and its customers by quarter end before recognizing revenue. CA's reported revenue and earnings per share (EPS) appeared to meet or exceed Wall Street analysts' expectations, when-in truth and fact-those results were based in part on revenue that CA recognized prematurely and in violation of GAAP. 1

Audit Committee Investigation

In 2003, CA announced that the Audit Committee of its Board of Directors was conducting an investigation into the timing of revenue recognition at the company. On April 26, 2004, CA filed with the SEC a Form 8-K ("Form 8-K") stating, among other things, that:

"The Audit Committee's investigation found accounting irregularities that led to material misstatements of the Company's financial reports for fiscal years 2000 and 2001, and prior periods. The effect of prior period errors which have an impact on fiscal year 2000 have been considered as part of this restatement. The Audit Committee believes that several factors contributed to the improper recognition of revenue in these periods, including a practice of holding the financial period open after the end of the fiscal quarters, providing customers with contracts with preprinted signature dates, late countersignatures by Company personnel, backdating of contracts, and not having sufficient controls to ensure the proper accounting. In addition, the Audit Committee found that certain former executives and other personnel were engaged in the practice of "cleaning up" contracts by, among other things, removing fax time stamps before providing agreements to the outside auditors. These same executives and personnel also misled the Company's outside counsel, the Audit Committee and its counsel and accounting advisers regarding these accounting practices."

Also in the Form 8-K, CA announced that it was restating over $2.2 billion in revenue that CA had recognized improperly in FY2000 and FY2001.

Improper Revenue Recognition at CA

From at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001, CA derived its income primarily from licensing software and providing maintenance for that software. CA's software operated and maintained powerful "mainframe" computers, those generally used by businesses and other organizations. Prior to October 2000, CA's contract and licensing model involved entering into long-term licensing contracts, some as long as seven years in duration. Under that business model, customers paid an initial licensing fee for the software, plus subsequent licensing fees for the right to use the software in subsequent years. In addition, customers paid CA for ongoing maintenance, such as technical support. Customers often entered into long-term contracts and spread out the licensing and maintenance fees over the term of the contract.

For contracts under its pre-October 2000 business model, GAAP allowed CA to recognize all the license revenue called for during the duration of the contract up front, during the fiscal quarter in which the software was shipped and the contract was executed and final.

SOP 97-2 , 2 which the AICPA adopted in October 1997, requires the following before revenue can be recognized from a software sale:

• Evidence of an arrangement

• Delivery

• Fixed and determinable fees

• Ability to collect

When a software company uses contracts requiring signatures by the software company and its customer, then SOP 97-2 provides that both signatures-the software company and the customer-are required as "evidence of an arrangement" before the software company may recognize revenue. During the period in question, all CA's license agreements required signatures by both CA and the customer.

Materially False Statements and Omissions in Filings with the SEC

During at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001, CA violated GAAP, including SOP 97-2 , by backdating software contracts into prior fiscal quarters expired software contracts that were not executed-and for which "evidence of an arrangement" did not exist-until a subsequent quarter. This extended quarters practice resulted in CA's premature recognition of revenue. As a consequence, CA made material misrepresentations and omissions of fact concerning CA's revenues and earnings for the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001 in various public documents and in connection with the offer, purchase, and sale of securities. CA's reported results for at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the fourth quarter of FY2000 appeared to meet or exceed the revenue and earnings estimates of outside analysts when, in fact, those reported results did not comply with GAAP and were false and misleading.

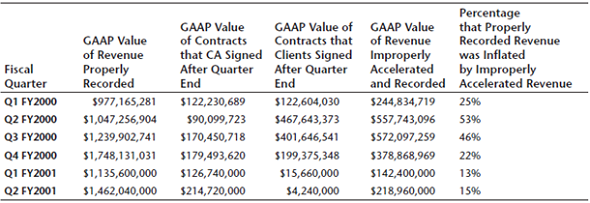

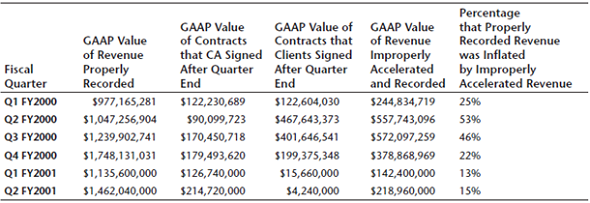

In its Form 8-K, which was not an audited restatement, CA admits that the extended quarters practice resulted in CA prematurely recognizing substantial percentages of revenue for all quarters of FY2000 and the first two quarters of FY2001. The following chart illustrates the impact of the premature revenue recognition in each fiscal quarter:

The greatest amount of prematurely recognized revenue as a result of the extended quarters practice occurred in FY2000, particularly in the third quarter, followed by the second, fourth and first quarters of that fiscal year. If CA had not improperly recognized revenue in each of those fiscal quarters, CA would not have met analysts' revenue and earnings estimates.

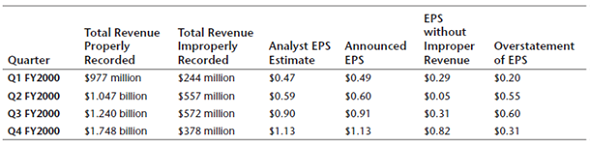

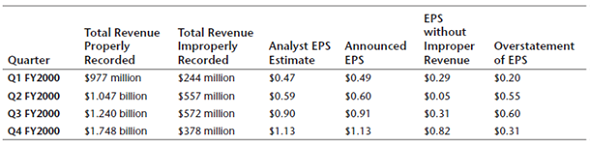

The following is a chart which shows the impact of the extended quarters practice on CA's earnings per share in the four quarters of FY2000 and the extent of the material misstatements and misrepresentations in the Forms 10-Q and Form 10-K that CA filed with the SEC which reported each quarterly result, and related public statements made by CA:

A Systemic and Intentional Practice

The premature recognition of revenue at CA during at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001 was the result of a systemic, intentional practice by certain CA personnel. To implement and conceal this extended quarters practice, CA personnel employed a variety of improper techniques, many of which rendered the company's books and records false and misleading, including:

• Some employees at CA called the extended quarters practice the "35-day month" practice, because generally most quarters were extended by at least 3 business days, although some quarterly extensions lasted longer.

• Sometimes CA had its customers execute contracts bearing preprinted dates from the just-expired quarter, even though the customer did not actually sign the contract until days or weeks into the new quarter.

CA substantially stopped prematurely recognizing revenue for software contracts signed after quarter end by CA's customers during the first quarter of FY2001 (quarter ended June 30, 2000). That quarter, CA missed its Wall Street earnings estimates. CA issued a press release on July 3, 2000, stating that it would miss the analysts' estimates, specifically citing the fact that the company did not complete several large contracts that they had hoped to conclude before the close of the quarter. This was only the second time in CA's then-recent history that CA missed Wall Street's estimates. The next trading day, July 5, 2000, CA's share price dropped over 43 percent, from $51.12 to $28.50, as the market reacted to the news. The share price has not recovered and closed at $26.26 on June 14, 2013.

CA continued to recognize revenue prematurely from contracts that CA signed after quarter end (although, with a few exceptions, the customer did sign the contract by quarter end) for the first two quarters of FY2001, after which that practice substantially stopped.

Legal Matters Resolved

In September 2004, CA agreed to pay $225 million in restitution to shareholders to settle the civil case brought by the SEC and to defer criminal charges by the U.S. Department of Justice. At the same time, a federal grand jury brought criminal charges against former CA chairman and CEO Sanjay Kumar. Kumar resigned in April 2004 following an investigation into securities fraud and obstruction of justice at CA. A federal grand jury in Brooklyn indicted him on fraud charges on September 22, 2004. Kumar pled guilty to obstruction of justice and securities fraud charges on April 24, 2006. On November 2, 2006, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison and fined $8 million for his role in the massive accounting fraud at CA. Kumar is currently housed at the Federal Correctional Institution in Miami, Florida, with a projected release date of January 25, 2018.

Questions

1. Analyze each revenue recognition technique identified in the audit committee investigation and explain whether each technique violates revenue recognition rules in accounting. Evaluate the practices followed by CA from an ethical perspective.

2. CA executives were not accused of reporting nonexistent deals or hiding major flaws in the business. The contracts that were backdated by a few days were real. Was this really a crime, or should it fall under the heading of "no harm, no foul"? Be sure to use ethical reasoning in responding to the question.

3. In her "Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse," which were discussed in Chapter 3, Marianne Jennings listed "pressure to maintain the numbers" as the number one sign. How can a company like CA resist such pressure?

1 The material in this case is taken from the SEC complaint against CA that can be found at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/comp18891-cai.pdf.

2 SOPs are pronouncements on specific accounting matters that had been issued by the AICPA's Accounting Standards Division from 1974 to 2009. The FASB GAAP Codification of authoritative accounting standards issued in 2009 supersedes existing sources of US GAAP including Statements of Position.

Computer Associates (CA) is a business consulting and software development company that designs, markets, and licenses computer software products that allow businesses to run and manage critical aspects of their information technology efficiently. CA's stock trades on the NYSE and is registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Exchange Act, 15 U.S.C. §78l(b).

Between about the fourth quarter of fiscal year (FY) 1998 through the second quarter of FY2001, CA engaged in a widespread practice that allowed for the premature recognition of revenue from software licensing agreements. CA personnel recorded, into the just-elapsed fiscal quarter, revenue from software contracts that were not finalized and signed by both CA and its customers until days or weeks after that quarter ended. The reported revenue was improper because it violated GAAP, which required that license agreements be fully executed by both CA and its customers by quarter end before recognizing revenue. CA's reported revenue and earnings per share (EPS) appeared to meet or exceed Wall Street analysts' expectations, when-in truth and fact-those results were based in part on revenue that CA recognized prematurely and in violation of GAAP. 1

Audit Committee Investigation

In 2003, CA announced that the Audit Committee of its Board of Directors was conducting an investigation into the timing of revenue recognition at the company. On April 26, 2004, CA filed with the SEC a Form 8-K ("Form 8-K") stating, among other things, that:

"The Audit Committee's investigation found accounting irregularities that led to material misstatements of the Company's financial reports for fiscal years 2000 and 2001, and prior periods. The effect of prior period errors which have an impact on fiscal year 2000 have been considered as part of this restatement. The Audit Committee believes that several factors contributed to the improper recognition of revenue in these periods, including a practice of holding the financial period open after the end of the fiscal quarters, providing customers with contracts with preprinted signature dates, late countersignatures by Company personnel, backdating of contracts, and not having sufficient controls to ensure the proper accounting. In addition, the Audit Committee found that certain former executives and other personnel were engaged in the practice of "cleaning up" contracts by, among other things, removing fax time stamps before providing agreements to the outside auditors. These same executives and personnel also misled the Company's outside counsel, the Audit Committee and its counsel and accounting advisers regarding these accounting practices."

Also in the Form 8-K, CA announced that it was restating over $2.2 billion in revenue that CA had recognized improperly in FY2000 and FY2001.

Improper Revenue Recognition at CA

From at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001, CA derived its income primarily from licensing software and providing maintenance for that software. CA's software operated and maintained powerful "mainframe" computers, those generally used by businesses and other organizations. Prior to October 2000, CA's contract and licensing model involved entering into long-term licensing contracts, some as long as seven years in duration. Under that business model, customers paid an initial licensing fee for the software, plus subsequent licensing fees for the right to use the software in subsequent years. In addition, customers paid CA for ongoing maintenance, such as technical support. Customers often entered into long-term contracts and spread out the licensing and maintenance fees over the term of the contract.

For contracts under its pre-October 2000 business model, GAAP allowed CA to recognize all the license revenue called for during the duration of the contract up front, during the fiscal quarter in which the software was shipped and the contract was executed and final.

SOP 97-2 , 2 which the AICPA adopted in October 1997, requires the following before revenue can be recognized from a software sale:

• Evidence of an arrangement

• Delivery

• Fixed and determinable fees

• Ability to collect

When a software company uses contracts requiring signatures by the software company and its customer, then SOP 97-2 provides that both signatures-the software company and the customer-are required as "evidence of an arrangement" before the software company may recognize revenue. During the period in question, all CA's license agreements required signatures by both CA and the customer.

Materially False Statements and Omissions in Filings with the SEC

During at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001, CA violated GAAP, including SOP 97-2 , by backdating software contracts into prior fiscal quarters expired software contracts that were not executed-and for which "evidence of an arrangement" did not exist-until a subsequent quarter. This extended quarters practice resulted in CA's premature recognition of revenue. As a consequence, CA made material misrepresentations and omissions of fact concerning CA's revenues and earnings for the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001 in various public documents and in connection with the offer, purchase, and sale of securities. CA's reported results for at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the fourth quarter of FY2000 appeared to meet or exceed the revenue and earnings estimates of outside analysts when, in fact, those reported results did not comply with GAAP and were false and misleading.

In its Form 8-K, which was not an audited restatement, CA admits that the extended quarters practice resulted in CA prematurely recognizing substantial percentages of revenue for all quarters of FY2000 and the first two quarters of FY2001. The following chart illustrates the impact of the premature revenue recognition in each fiscal quarter:

The greatest amount of prematurely recognized revenue as a result of the extended quarters practice occurred in FY2000, particularly in the third quarter, followed by the second, fourth and first quarters of that fiscal year. If CA had not improperly recognized revenue in each of those fiscal quarters, CA would not have met analysts' revenue and earnings estimates.

The following is a chart which shows the impact of the extended quarters practice on CA's earnings per share in the four quarters of FY2000 and the extent of the material misstatements and misrepresentations in the Forms 10-Q and Form 10-K that CA filed with the SEC which reported each quarterly result, and related public statements made by CA:

A Systemic and Intentional Practice

The premature recognition of revenue at CA during at least the fourth quarter of FY1998 through the second quarter of FY2001 was the result of a systemic, intentional practice by certain CA personnel. To implement and conceal this extended quarters practice, CA personnel employed a variety of improper techniques, many of which rendered the company's books and records false and misleading, including:

• Some employees at CA called the extended quarters practice the "35-day month" practice, because generally most quarters were extended by at least 3 business days, although some quarterly extensions lasted longer.

• Sometimes CA had its customers execute contracts bearing preprinted dates from the just-expired quarter, even though the customer did not actually sign the contract until days or weeks into the new quarter.

CA substantially stopped prematurely recognizing revenue for software contracts signed after quarter end by CA's customers during the first quarter of FY2001 (quarter ended June 30, 2000). That quarter, CA missed its Wall Street earnings estimates. CA issued a press release on July 3, 2000, stating that it would miss the analysts' estimates, specifically citing the fact that the company did not complete several large contracts that they had hoped to conclude before the close of the quarter. This was only the second time in CA's then-recent history that CA missed Wall Street's estimates. The next trading day, July 5, 2000, CA's share price dropped over 43 percent, from $51.12 to $28.50, as the market reacted to the news. The share price has not recovered and closed at $26.26 on June 14, 2013.

CA continued to recognize revenue prematurely from contracts that CA signed after quarter end (although, with a few exceptions, the customer did sign the contract by quarter end) for the first two quarters of FY2001, after which that practice substantially stopped.

Legal Matters Resolved

In September 2004, CA agreed to pay $225 million in restitution to shareholders to settle the civil case brought by the SEC and to defer criminal charges by the U.S. Department of Justice. At the same time, a federal grand jury brought criminal charges against former CA chairman and CEO Sanjay Kumar. Kumar resigned in April 2004 following an investigation into securities fraud and obstruction of justice at CA. A federal grand jury in Brooklyn indicted him on fraud charges on September 22, 2004. Kumar pled guilty to obstruction of justice and securities fraud charges on April 24, 2006. On November 2, 2006, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison and fined $8 million for his role in the massive accounting fraud at CA. Kumar is currently housed at the Federal Correctional Institution in Miami, Florida, with a projected release date of January 25, 2018.

Questions

1. Analyze each revenue recognition technique identified in the audit committee investigation and explain whether each technique violates revenue recognition rules in accounting. Evaluate the practices followed by CA from an ethical perspective.

2. CA executives were not accused of reporting nonexistent deals or hiding major flaws in the business. The contracts that were backdated by a few days were real. Was this really a crime, or should it fall under the heading of "no harm, no foul"? Be sure to use ethical reasoning in responding to the question.

3. In her "Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse," which were discussed in Chapter 3, Marianne Jennings listed "pressure to maintain the numbers" as the number one sign. How can a company like CA resist such pressure?

1 The material in this case is taken from the SEC complaint against CA that can be found at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/comp18891-cai.pdf.

2 SOPs are pronouncements on specific accounting matters that had been issued by the AICPA's Accounting Standards Division from 1974 to 2009. The FASB GAAP Codification of authoritative accounting standards issued in 2009 supersedes existing sources of US GAAP including Statements of Position.

1. Accrual earnings are income that has been earned but not yet received in cash. For example, a contractor who completed a construction project but not paid yet. These are considered "earned" when the customer finishes the purchases, e.g. contract signed or delivery made. The revenue on the company's financial statements were inflated due to recognizing income that has not been earned. The objectionable practices listed

• 35 month days, extends the revenue recognition period

• Dating contracts with earlier dates that were signed later

The company violated its responsibility to its stockholders to keep accurate records. They also misled stockholders of their earning strength. 2. Just because a crime doesn't hurt anyone doesn't mean that there are no repercussions. By backdating contracts the revenues were inflated, making the company look better financially than it actually was. Investors use this information for their portfolio. But since this information is not accurate this causes losses to investors later on when the revenues have to be corrected for. The company also gives a poor ethical image for its employees to follow by condoning such practices. 3. These companies need to realize that the numbers are only allocated, shifted. By reporting revenues earned say in December when it's actually earned in January, it only shifts the numbers down. The company will have to keep up this practice. Furthermore, shifting numbers doesn't help the company financially in the long run. In the long run, their revenue are determined by their products and services not by shifting numbers.

• 35 month days, extends the revenue recognition period

• Dating contracts with earlier dates that were signed later

The company violated its responsibility to its stockholders to keep accurate records. They also misled stockholders of their earning strength. 2. Just because a crime doesn't hurt anyone doesn't mean that there are no repercussions. By backdating contracts the revenues were inflated, making the company look better financially than it actually was. Investors use this information for their portfolio. But since this information is not accurate this causes losses to investors later on when the revenues have to be corrected for. The company also gives a poor ethical image for its employees to follow by condoning such practices. 3. These companies need to realize that the numbers are only allocated, shifted. By reporting revenues earned say in December when it's actually earned in January, it only shifts the numbers down. The company will have to keep up this practice. Furthermore, shifting numbers doesn't help the company financially in the long run. In the long run, their revenue are determined by their products and services not by shifting numbers.

2

What is the purpose of audit "risk assessment"? What are its objectives, and why is it important in assessing the likelihood that fraud may occur?

Risk assessment is the identification of risk factors that will negatively impact a business. For auditing the important risk are fraud. Fraud is a deliberate attempt to deceive, such as lying about business expenses or misreporting the actual revenue earned. By identifying fraud risk, auditors can advise management on safeguards to prevent it. Doing so improves internal control.

3

ZZZZ Best 1

The story of ZZZZ Best is one of greed and audaciousness. It is the story of a 15-year-old boy from Reseda, California, who was driven to be successful regardless of the costs. His name is Barry Minkow.

Minkow had high hopes to make it big-to be a millionaire very early in life. He started a carpet cleaning business in the garage of his home. But Minkow realized early on that he was not going to become a millionaire cleaning other people's carpets. He had grander plans than that. Minkow was going to make it big in the insurance restoration business. In other words, ZZZZ Best would contract to do carpet and drapery cleaning jobs after a fire or flood. Because the damage from the fire or flood probably would be covered by insurance, the customer would be eager to have the work done, and perhaps not be all that concerned with how much it would cost. The only problem with Minkow's insurance restoration idea was that it was all a fiction. There were no insurance restoration jobs-at least not for ZZZZ Best. Allegedly, over 80 percent of his revenue was from this work. In the process of creating the fraud, Minkow was able to dupe the auditors, Ernst Whinney (one of the predecessor firms of Ernst Young), into thinking the insurance restoration business was real. The auditors never caught on until it was too late.

How Barry Became a Fraudster

Minkow wrote a book, Clean Sweep: A Story of Compromise, Corruption, Collapse, and Comeback , 2 that provides some insights into the mind of a 15-year-old kid who was called a "wonder boy" on Wall Street until the bubble burst. He was trying to find a way to drum up customers for his fledgling carpet cleaning business. One day, while he was alone in his garage-office, Minkow called Channel 4 in Los Angeles. He disguised his voice so he wouldn't sound like a teenager and told a producer that he had just had his carpets cleaned by the 16-year-old owner of ZZZZ Best. He sold the producer on the idea that it would be good for society to hear the success story about a high school junior running his own business. The producer bought it lock, stock, and carpet cleaner. Minkow gave the producer the phone number of ZZZZ Best and waited. It took less than five minutes for the call to come in. Minkow answered the phone and when the producer asked to speak with Mr. Barry Minkow, Minkow said: "Who may I say is calling?" Within days, a film crew was in his garage shooting ZZZZ Best at work. The story aired that night, and it was followed by more calls from radio stations and other television shows wanting to do interviews. The calls flooded in with customers demanding that Barry Minkow personally clean their carpets.

As his income increased in the spring of 1983, Minkow found it increasingly difficult to run the company without a checking account. He managed to find a banker that was so moved by his story that the banker agreed to allow an underage customer to open a checking account. Minkow used the money to buy cleaning supplies and other necessities. Even though his business was growing, Minkow ran into trouble paying back loans and interest when due.

Minkow developed a plan of action. He was tired of worrying about not having enough money. He went to his garage-where all his great ideas first began-and looked at his bank account statement, which showed that he had more money than he thought he had based on his own records. Minkow soon realized it was because some checks he had written had not been cashed by customers, so they didn't yet show up on the bank statement. Voila! Minkow started to kite checks between two or more banks. He would write a check on one ZZZZ Best account and deposit it into another. Because it might take a few days for the check written on Bank #1 to clear that bank's records (back then, checks weren't always processed in real time the way they are today), Minkow could pay some bills out of the second account and Bank #1 would not know-at least for a few days-that Minkow had written a check on his account when, in reality, he had a negative balance. The bank didn't know it because some of the checks that Minkow had written before the visit to Bank #2 had not cleared his account in Bank #1.

It wasn't long thereafter that Minkow realized he could kite checks big time. Not only that, he could make the transfer of funds at the end of a month or a year and show a higher balance than really existed in Bank #1 and carry it onto the balance sheet. Because Minkow did not count the check written on his account in Bank #1 as an outstanding check, he was able to double-count.

Time to Expand the Fraud

Over time, Minkow moved on to bigger and bigger frauds, like having his trusted cohorts confirm to banks and other interested parties that ZZZZ Best was doing insurance restoration jobs. Minkow used the phony jobs and phony revenue to convince bankers to make loans to ZZZZ Best. He had cash remittance forms made up from nonexistent customers with whatever sales amount he wanted to appear on the document. He even had a co-conspirator write on the bogus remittance form, "Job well done." Minkow could then show a lot more revenue than he was really making.

Minkow's phony financial statements enabled him to borrow more and more money and expand the number of carpet cleaning outlets. However, Minkow's personal tastes had become increasingly more expensive, including purchasing a Ferrari with the borrowed funds and putting a down payment on a 5,000-square-foot home. So, the question was: How do you solve a perpetual cash flow problem? You go public! That's right, Minkow made a public offering of stock in ZZZZ Best. Of course, he owned a majority of the stock to maintain control of the company.

Minkow had made it to the big leagues. He was on Wall Street. He had investment bankers, CPAs, and attorneys all working for him-the now 19-year-old kid from Reseda, California, who had turned a mom-and-pop operation into a publicly owned corporation.

Barry Goes Public

Minkow's first audit was for the 12 months ended April 30, 1986. A sole practitioner performed the audit. (There are eerie similarities in the Madoff fraud, with its small practitioner firm-Friehling Horowitz-conducting the audit of a multibillion-dollar operation, and that of the sole practitioner audit of ZZZZ Best.)

Minkow had established two phony front companies that allegedly placed insurance restoration jobs for ZZZZ Best. He had one of his cohorts create invoices for services and respond to questions about the company. There was enough paperwork to fool the auditor into thinking the jobs were real and the revenue was supportable. However, the auditor never visited any of the insurance restoration sites. If he had done so, there would have been no question in his mind that ZZZZ Best was a big fraud.

Pressured to get a big-time CPA firm to do his audit as he moved into the big leagues, Minkow hired Ernst Whinney to perform the April 30, 1987, fiscal year-end audit. Minkow continued to be one step ahead of the auditors-that is, until the Ernst Whinney auditors insisted on going to see an insurance restoration site. They wanted to confirm that all the business-all the revenue-that Minkow had said was coming in to ZZZZ Best was real.

The engagement partner drove to an area in Sacramento, California, where Minkow did a lot of work-supposedly. He looked for a building that seemed to be a restoration job. Why he did that isn't clear, but he identified a building that seemed to be the kind that would be a restoration job in progress.

Earlier in the week, Minkow had sent one of his cohorts to find a large building in Sacramento that appeared to be a restoration site. As luck would have it, Minkow's associate picked out the same site as had the partner later on. Minkow's cohorts found the leasing agent for the building. They convinced the agent to give them the keys so that they could show the building to some potential tenants over the weekend. Minkow's helpers went up to the site before the arrival of the partner and placed placards on the walls that indicated ZZZZ Best was the contractor for the building restoration. In fact, the building was not fully constructed at the time, but it looked as if some restoration work was going on at the site.

Minkow was able to pull it off in part due to luck and in part because the Ernst and Whinney auditors did not want to lose the ZZZZ Best account. It had become a large revenue producer for the firm, and Minkow seemed destined for greater and greater achievements. Minkow was smart and used the leverage of the auditors not wanting to lose the ZZZZ Best account as a way to complain whenever they became too curious about the insurance restoration jobs. He would even threaten to take his business from Ernst and Whinney and give it to other auditors.

Minkow also took a precaution with the site visit. He had the auditors sign a confidentiality agreement that they would not make any follow-up calls to any contractors, insurance companies, the building owner, or other individuals involved in the restoration work. This prevented the auditors from corroborating the insurance restoration contracts with independent third parties. The auditors clearly dropped the ball here as the firm failed to gather the evidence necessary to support the existence of the work and revenue-production from the insurance restoration contracts.

The Fraud Starts to Unravel

It was a Los Angeles housewife who started the problems for ZZZZ Best that would eventually lead to the company's demise. Because Minkow was a well-known figure and flamboyant character, the Los Angeles Times did a story about the carpet cleaning business. The Los Angeles housewife read the story about Minkow and recalled that ZZZZ Best had overcharged her for services in the early years by increasing the amount of the credit card charge for its carpet cleaning services.

Minkow had gambled that most people don't check their monthly statements, so he could get away with the petty fraud. However, the housewife did notice the overcharge and complained to Minkow, and eventually he returned the overpayment. She couldn't understand why Minkow would have had to resort to such low levels back then if he was as successful as the Times article made him out to be. So, she called the reporter to find out more, and that ultimately led to the investigation of ZZZZ Best and future stories that weren't so flattering.

Because Minkow continued to spend lavishly on himself and his possessions, he always seemed to need more and more money. It got so bad over time that he was close to defaulting on loans and had to make up stories to keep the creditors at bay, and he couldn't pay his suppliers. The complaints kept coming in, and eventually the house of cards that was ZZZZ Best came crashing down.

During the time that the fraud was unraveling, Ernst and Whinney decided to resign from the ZZZZ Best audit. The firm never did issue an audit report. It had started to doubt the veracity of Minkow and his business at ZZZZ Best.

The procedure to follow when a change of auditor occurs is for the company being audited to file an 8-K form with the SEC and the audit firm to prepare an exhibit commenting on the accuracy of the disclosures in the 8-K. The exhibit is attached to the form that is sent to the SEC within 30 days of the change. 3 Ernst Whinney waited the full 30-day period, and the SEC released the information to the public 45 days after the change had occurred. Meanwhile, ZZZZ Best filed for bankruptcy. During the period of time that had elapsed, Minkow had borrowed more than $1 million, and the lenders never were repaid. Bankruptcy laws protected Minkow and ZZZZ Best from having to make those payments.

Legal Liability Issues

The ZZZZ Best fraud was one of the largest of its time. ZZZZ Best reportedly settled a shareholder class action lawsuit for $35 million. Ernst Whinney was sued by a bank that had made a multimillion-dollar loan based on the financial statements for the three-month period ending July 31, 1986. The bank claimed that it had relied on the review report issued by Ernst Whinney in granting the loan to ZZZZ Best. However, the firm had indicated in its review report that it was not issuing an opinion on the ZZZZ Best financial statements. The judge ruled that the bank was not justified in relying on the review report because Ernst Whinney had expressly disclaimed issuing any opinion on the statements.

Barry Minkow was charged with engaging in a $100 million fraud scheme. He was sentenced to a term of 25 years.

Questions

1. Do you believe that auditors should be held liable for failing to discover fraud in situations such as ZZZZ Best, where top management goes to great lengths to fool the auditors? Answer this question with respect to the ethical and professional responsibilities of audit professionals when conducting an audit.

2. Discuss the red flags that existed in the ZZZZ Best case and evaluate Ernst Whinney's efforts with respect to fraud risk assessment. Do you think Ernst Whinney's relationship with ZZZZ Best influenced risk assessment and the work done on the audit?

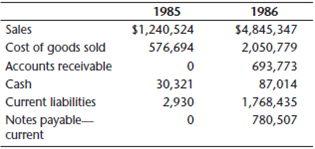

3. These are selected numbers from the financial statements of ZZZZ Best for fiscal years

4. Evaluate Minkow's actions using the fraud triangle.

What calculations or analyses would you make with these numbers that might help you assess whether the financial relationships are "reasonable"? Given the facts of the case, what inquiries might you make of management based on your analysis?

Barry: The Afterlife

After being released from jail in 1995, Minkow became a preacher and a fraud investigator, and he spoke at schools about ethics. This all came to an end in 2011, when he admitted to helping deliberately drive down the stock price of Lennar, a home-building company, and was sent back to prison. The facts below explain what happened to Barry since 1995.

In 1997, Minkow became the senior pastor of Community Bible Church in San Diego. Soon after his arrival, a church member asked him to look into a money management firm in nearby Orange County. Suspecting something was not right, Minkow used his "fraud-sniffing" abilities to alert federal authorities, who discovered the firm was a $300 million pyramid scheme. This was the beginning of the Fraud Discovery Institute, a for-profit investigative firm. Minkow managed to dupe the investment community again; several Wall Street investors liked what they saw and sent him enough money to go after bigger targets. By Minkow's estimate, he had uncovered $1 billion worth of fraud over the years.

We assume that Minkow missed the adrenalin rush of committing fraud that kept him going for so long in the 1990s, and in 2009 he issued a report accusing the major homebuilder Lennar of massive fraud. Minkow claimed that irregularities in Lennar's off-balance-sheet debt accounting were evidence of a massive Ponzi scheme. He accused Lennar of not disclosing enough information about this to its shareholders, and also claimed that a Lennar executive took out a fraudulent personal loan. Minkow denounced Lennar as "a financial crime in progress" and "a corporate bully." From January 9, 2009 (when Minkow first made his accusations) to January 22, Lennar's stock tumbled from $11.57 a share to only $6.55. Minkow issued the report after being contacted by Nicholas Marsch, a San Diego developer who had filed two lawsuits against Lennar for fraud. One of Marsch's suits was summarily thrown out of court, while the other ended with Marsch having to pay Lennar $12 million in counterclaims.

Lennar responded by adding Minkow as a defendant in a libel-and-extortion suit against Marsch. According to court records, Minkow had shorted Lennar stock, buying $20,000 worth of options in a bet that the stock would fall. Minkow also forged documents alleging misconduct on Lennar's part. He went forward with the report even after a private investigator he had hired for the case could not substantiate Marsch's claims. (In an unrelated development, it was also revealed that Minkow operated the Fraud Discovery Institute out of the offices of his church and even used church money to fund it-something which could have potentially jeopardized his church's tax-exempt status.)

On December 27, 2010, Florida circuit court judge Gill Freeman issued terminating actions against Minkow in response to a motion by Lennar. Freeman found that Minkow had repeatedly lied under oath, destroyed or withheld evidence, concealed witnesses, and deliberately tried to "cover up his misconduct." According to Freeman, Minkow had even lied to his own lawyers about his behavior. Freeman determined that Minkow had perpetuated "a fraud on the court" that was so egregious that letting the case go any further would be a disservice to justice. In her view, "no remedy short of default" was appropriate for Minkow's lies. She ordered Minkow to reimburse Lennar for the legal expenses it incurred while ferreting out his lies. Lennar estimates that its attorneys and investigators spent hundreds of millions of dollars exposing Minkow's lies.

On March 16, 2011, Minkow announced through his attorney that he was pleading guilty to one count of insider trading. According to his lawyer, Minkow had bought his Lennar options using "nonpublic information." The plea, which was separate from the civil suit, came a month after Minkow learned that he was the subject of a criminal investigation. Minkow claimed not to know at the time that he was breaking the law. The SEC had already been probing Minkow's trading practices. On the same day, Minkow resigned his position as senior pastor, saying in a letter to his flock that because he was no longer "above reproach," he felt that he was "no longer qualified to be a pastor." Six weeks earlier, $50,000 in cash and checks was stolen from the church during a burglary. Though unsolved, it was noted as suspicious due to Minkow's admitted history of staging burglaries to collect insurance money.

The nature of the "nonpublic information" became clear a week later, when federal prosecutors filed a criminal information action against Minkow, with one count of conspiracy to commit securities fraud. Prosecutors charged that Minkow and Marsch conspired to extort money from Lennar by driving down its stock. The complaint also revealed that Minkow had sent his allegations to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and SEC, and that the three agencies found his claims credible enough to open a formal criminal investigation into Lennar's practices. Minkow then used confidential knowledge of that investigation to short Lennar stock, even though he knew he was barred from doing so. Minkow opted to plead guilty to the conspiracy charge rather than face charges of securities fraud and market manipulation, which could have sent him to prison for life.

On March 30, 2011, Minkow pleaded guilty and was eventually sent to jail for five years and ordered to pay Lennar $584 million in damages-roughly the amount the company lost as a result of the bear raid. The ruling stated that Minkow and Marsch had entered into a conspiracy to wreck Lennar's stock in November 2008. With interest, the bill could easily approach $1 billion-far more than he stole in the ZZZZ Best scam.

Questions ( continued )

5. What factors do you think motivated Minkow to return to his evil ways after becoming a respected member of the community following his release from prison in the ZZZZ Best fraud?

6. Using Kohlberg's stages of moral development, how would you characterize Minkow's actions after being released from prison in the ZZZZ Best fraud? Explain the effects of Minkow's actions on the stakeholders who relied on him to act in a professional manner.

1 The facts are derived from a video by the ACFE, Cooking the Books: What Every Accountant Should Know about Fraud.

2 Barry Minkow, Clean Sweep: A Story of Compromise, Corruption, Collapse, and Comeback (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1995).

3 Under current SEC rules, Item 4.01 of Form 8-K requires a company to request the former accountant to furnish a letter stating whether the former accountant agrees with the company's statements concerning the reasons for the change. Where the former accountant declines to provide such a letter, the company should indicate that fact in the Form 8-K. The company must file the 8-K report for the change in accountant within five business days of notification.

The story of ZZZZ Best is one of greed and audaciousness. It is the story of a 15-year-old boy from Reseda, California, who was driven to be successful regardless of the costs. His name is Barry Minkow.

Minkow had high hopes to make it big-to be a millionaire very early in life. He started a carpet cleaning business in the garage of his home. But Minkow realized early on that he was not going to become a millionaire cleaning other people's carpets. He had grander plans than that. Minkow was going to make it big in the insurance restoration business. In other words, ZZZZ Best would contract to do carpet and drapery cleaning jobs after a fire or flood. Because the damage from the fire or flood probably would be covered by insurance, the customer would be eager to have the work done, and perhaps not be all that concerned with how much it would cost. The only problem with Minkow's insurance restoration idea was that it was all a fiction. There were no insurance restoration jobs-at least not for ZZZZ Best. Allegedly, over 80 percent of his revenue was from this work. In the process of creating the fraud, Minkow was able to dupe the auditors, Ernst Whinney (one of the predecessor firms of Ernst Young), into thinking the insurance restoration business was real. The auditors never caught on until it was too late.

How Barry Became a Fraudster

Minkow wrote a book, Clean Sweep: A Story of Compromise, Corruption, Collapse, and Comeback , 2 that provides some insights into the mind of a 15-year-old kid who was called a "wonder boy" on Wall Street until the bubble burst. He was trying to find a way to drum up customers for his fledgling carpet cleaning business. One day, while he was alone in his garage-office, Minkow called Channel 4 in Los Angeles. He disguised his voice so he wouldn't sound like a teenager and told a producer that he had just had his carpets cleaned by the 16-year-old owner of ZZZZ Best. He sold the producer on the idea that it would be good for society to hear the success story about a high school junior running his own business. The producer bought it lock, stock, and carpet cleaner. Minkow gave the producer the phone number of ZZZZ Best and waited. It took less than five minutes for the call to come in. Minkow answered the phone and when the producer asked to speak with Mr. Barry Minkow, Minkow said: "Who may I say is calling?" Within days, a film crew was in his garage shooting ZZZZ Best at work. The story aired that night, and it was followed by more calls from radio stations and other television shows wanting to do interviews. The calls flooded in with customers demanding that Barry Minkow personally clean their carpets.

As his income increased in the spring of 1983, Minkow found it increasingly difficult to run the company without a checking account. He managed to find a banker that was so moved by his story that the banker agreed to allow an underage customer to open a checking account. Minkow used the money to buy cleaning supplies and other necessities. Even though his business was growing, Minkow ran into trouble paying back loans and interest when due.

Minkow developed a plan of action. He was tired of worrying about not having enough money. He went to his garage-where all his great ideas first began-and looked at his bank account statement, which showed that he had more money than he thought he had based on his own records. Minkow soon realized it was because some checks he had written had not been cashed by customers, so they didn't yet show up on the bank statement. Voila! Minkow started to kite checks between two or more banks. He would write a check on one ZZZZ Best account and deposit it into another. Because it might take a few days for the check written on Bank #1 to clear that bank's records (back then, checks weren't always processed in real time the way they are today), Minkow could pay some bills out of the second account and Bank #1 would not know-at least for a few days-that Minkow had written a check on his account when, in reality, he had a negative balance. The bank didn't know it because some of the checks that Minkow had written before the visit to Bank #2 had not cleared his account in Bank #1.

It wasn't long thereafter that Minkow realized he could kite checks big time. Not only that, he could make the transfer of funds at the end of a month or a year and show a higher balance than really existed in Bank #1 and carry it onto the balance sheet. Because Minkow did not count the check written on his account in Bank #1 as an outstanding check, he was able to double-count.

Time to Expand the Fraud

Over time, Minkow moved on to bigger and bigger frauds, like having his trusted cohorts confirm to banks and other interested parties that ZZZZ Best was doing insurance restoration jobs. Minkow used the phony jobs and phony revenue to convince bankers to make loans to ZZZZ Best. He had cash remittance forms made up from nonexistent customers with whatever sales amount he wanted to appear on the document. He even had a co-conspirator write on the bogus remittance form, "Job well done." Minkow could then show a lot more revenue than he was really making.

Minkow's phony financial statements enabled him to borrow more and more money and expand the number of carpet cleaning outlets. However, Minkow's personal tastes had become increasingly more expensive, including purchasing a Ferrari with the borrowed funds and putting a down payment on a 5,000-square-foot home. So, the question was: How do you solve a perpetual cash flow problem? You go public! That's right, Minkow made a public offering of stock in ZZZZ Best. Of course, he owned a majority of the stock to maintain control of the company.

Minkow had made it to the big leagues. He was on Wall Street. He had investment bankers, CPAs, and attorneys all working for him-the now 19-year-old kid from Reseda, California, who had turned a mom-and-pop operation into a publicly owned corporation.

Barry Goes Public

Minkow's first audit was for the 12 months ended April 30, 1986. A sole practitioner performed the audit. (There are eerie similarities in the Madoff fraud, with its small practitioner firm-Friehling Horowitz-conducting the audit of a multibillion-dollar operation, and that of the sole practitioner audit of ZZZZ Best.)

Minkow had established two phony front companies that allegedly placed insurance restoration jobs for ZZZZ Best. He had one of his cohorts create invoices for services and respond to questions about the company. There was enough paperwork to fool the auditor into thinking the jobs were real and the revenue was supportable. However, the auditor never visited any of the insurance restoration sites. If he had done so, there would have been no question in his mind that ZZZZ Best was a big fraud.

Pressured to get a big-time CPA firm to do his audit as he moved into the big leagues, Minkow hired Ernst Whinney to perform the April 30, 1987, fiscal year-end audit. Minkow continued to be one step ahead of the auditors-that is, until the Ernst Whinney auditors insisted on going to see an insurance restoration site. They wanted to confirm that all the business-all the revenue-that Minkow had said was coming in to ZZZZ Best was real.

The engagement partner drove to an area in Sacramento, California, where Minkow did a lot of work-supposedly. He looked for a building that seemed to be a restoration job. Why he did that isn't clear, but he identified a building that seemed to be the kind that would be a restoration job in progress.

Earlier in the week, Minkow had sent one of his cohorts to find a large building in Sacramento that appeared to be a restoration site. As luck would have it, Minkow's associate picked out the same site as had the partner later on. Minkow's cohorts found the leasing agent for the building. They convinced the agent to give them the keys so that they could show the building to some potential tenants over the weekend. Minkow's helpers went up to the site before the arrival of the partner and placed placards on the walls that indicated ZZZZ Best was the contractor for the building restoration. In fact, the building was not fully constructed at the time, but it looked as if some restoration work was going on at the site.

Minkow was able to pull it off in part due to luck and in part because the Ernst and Whinney auditors did not want to lose the ZZZZ Best account. It had become a large revenue producer for the firm, and Minkow seemed destined for greater and greater achievements. Minkow was smart and used the leverage of the auditors not wanting to lose the ZZZZ Best account as a way to complain whenever they became too curious about the insurance restoration jobs. He would even threaten to take his business from Ernst and Whinney and give it to other auditors.

Minkow also took a precaution with the site visit. He had the auditors sign a confidentiality agreement that they would not make any follow-up calls to any contractors, insurance companies, the building owner, or other individuals involved in the restoration work. This prevented the auditors from corroborating the insurance restoration contracts with independent third parties. The auditors clearly dropped the ball here as the firm failed to gather the evidence necessary to support the existence of the work and revenue-production from the insurance restoration contracts.

The Fraud Starts to Unravel

It was a Los Angeles housewife who started the problems for ZZZZ Best that would eventually lead to the company's demise. Because Minkow was a well-known figure and flamboyant character, the Los Angeles Times did a story about the carpet cleaning business. The Los Angeles housewife read the story about Minkow and recalled that ZZZZ Best had overcharged her for services in the early years by increasing the amount of the credit card charge for its carpet cleaning services.

Minkow had gambled that most people don't check their monthly statements, so he could get away with the petty fraud. However, the housewife did notice the overcharge and complained to Minkow, and eventually he returned the overpayment. She couldn't understand why Minkow would have had to resort to such low levels back then if he was as successful as the Times article made him out to be. So, she called the reporter to find out more, and that ultimately led to the investigation of ZZZZ Best and future stories that weren't so flattering.

Because Minkow continued to spend lavishly on himself and his possessions, he always seemed to need more and more money. It got so bad over time that he was close to defaulting on loans and had to make up stories to keep the creditors at bay, and he couldn't pay his suppliers. The complaints kept coming in, and eventually the house of cards that was ZZZZ Best came crashing down.

During the time that the fraud was unraveling, Ernst and Whinney decided to resign from the ZZZZ Best audit. The firm never did issue an audit report. It had started to doubt the veracity of Minkow and his business at ZZZZ Best.

The procedure to follow when a change of auditor occurs is for the company being audited to file an 8-K form with the SEC and the audit firm to prepare an exhibit commenting on the accuracy of the disclosures in the 8-K. The exhibit is attached to the form that is sent to the SEC within 30 days of the change. 3 Ernst Whinney waited the full 30-day period, and the SEC released the information to the public 45 days after the change had occurred. Meanwhile, ZZZZ Best filed for bankruptcy. During the period of time that had elapsed, Minkow had borrowed more than $1 million, and the lenders never were repaid. Bankruptcy laws protected Minkow and ZZZZ Best from having to make those payments.

Legal Liability Issues

The ZZZZ Best fraud was one of the largest of its time. ZZZZ Best reportedly settled a shareholder class action lawsuit for $35 million. Ernst Whinney was sued by a bank that had made a multimillion-dollar loan based on the financial statements for the three-month period ending July 31, 1986. The bank claimed that it had relied on the review report issued by Ernst Whinney in granting the loan to ZZZZ Best. However, the firm had indicated in its review report that it was not issuing an opinion on the ZZZZ Best financial statements. The judge ruled that the bank was not justified in relying on the review report because Ernst Whinney had expressly disclaimed issuing any opinion on the statements.

Barry Minkow was charged with engaging in a $100 million fraud scheme. He was sentenced to a term of 25 years.

Questions

1. Do you believe that auditors should be held liable for failing to discover fraud in situations such as ZZZZ Best, where top management goes to great lengths to fool the auditors? Answer this question with respect to the ethical and professional responsibilities of audit professionals when conducting an audit.

2. Discuss the red flags that existed in the ZZZZ Best case and evaluate Ernst Whinney's efforts with respect to fraud risk assessment. Do you think Ernst Whinney's relationship with ZZZZ Best influenced risk assessment and the work done on the audit?

3. These are selected numbers from the financial statements of ZZZZ Best for fiscal years

4. Evaluate Minkow's actions using the fraud triangle.

What calculations or analyses would you make with these numbers that might help you assess whether the financial relationships are "reasonable"? Given the facts of the case, what inquiries might you make of management based on your analysis?

Barry: The Afterlife

After being released from jail in 1995, Minkow became a preacher and a fraud investigator, and he spoke at schools about ethics. This all came to an end in 2011, when he admitted to helping deliberately drive down the stock price of Lennar, a home-building company, and was sent back to prison. The facts below explain what happened to Barry since 1995.

In 1997, Minkow became the senior pastor of Community Bible Church in San Diego. Soon after his arrival, a church member asked him to look into a money management firm in nearby Orange County. Suspecting something was not right, Minkow used his "fraud-sniffing" abilities to alert federal authorities, who discovered the firm was a $300 million pyramid scheme. This was the beginning of the Fraud Discovery Institute, a for-profit investigative firm. Minkow managed to dupe the investment community again; several Wall Street investors liked what they saw and sent him enough money to go after bigger targets. By Minkow's estimate, he had uncovered $1 billion worth of fraud over the years.

We assume that Minkow missed the adrenalin rush of committing fraud that kept him going for so long in the 1990s, and in 2009 he issued a report accusing the major homebuilder Lennar of massive fraud. Minkow claimed that irregularities in Lennar's off-balance-sheet debt accounting were evidence of a massive Ponzi scheme. He accused Lennar of not disclosing enough information about this to its shareholders, and also claimed that a Lennar executive took out a fraudulent personal loan. Minkow denounced Lennar as "a financial crime in progress" and "a corporate bully." From January 9, 2009 (when Minkow first made his accusations) to January 22, Lennar's stock tumbled from $11.57 a share to only $6.55. Minkow issued the report after being contacted by Nicholas Marsch, a San Diego developer who had filed two lawsuits against Lennar for fraud. One of Marsch's suits was summarily thrown out of court, while the other ended with Marsch having to pay Lennar $12 million in counterclaims.

Lennar responded by adding Minkow as a defendant in a libel-and-extortion suit against Marsch. According to court records, Minkow had shorted Lennar stock, buying $20,000 worth of options in a bet that the stock would fall. Minkow also forged documents alleging misconduct on Lennar's part. He went forward with the report even after a private investigator he had hired for the case could not substantiate Marsch's claims. (In an unrelated development, it was also revealed that Minkow operated the Fraud Discovery Institute out of the offices of his church and even used church money to fund it-something which could have potentially jeopardized his church's tax-exempt status.)

On December 27, 2010, Florida circuit court judge Gill Freeman issued terminating actions against Minkow in response to a motion by Lennar. Freeman found that Minkow had repeatedly lied under oath, destroyed or withheld evidence, concealed witnesses, and deliberately tried to "cover up his misconduct." According to Freeman, Minkow had even lied to his own lawyers about his behavior. Freeman determined that Minkow had perpetuated "a fraud on the court" that was so egregious that letting the case go any further would be a disservice to justice. In her view, "no remedy short of default" was appropriate for Minkow's lies. She ordered Minkow to reimburse Lennar for the legal expenses it incurred while ferreting out his lies. Lennar estimates that its attorneys and investigators spent hundreds of millions of dollars exposing Minkow's lies.

On March 16, 2011, Minkow announced through his attorney that he was pleading guilty to one count of insider trading. According to his lawyer, Minkow had bought his Lennar options using "nonpublic information." The plea, which was separate from the civil suit, came a month after Minkow learned that he was the subject of a criminal investigation. Minkow claimed not to know at the time that he was breaking the law. The SEC had already been probing Minkow's trading practices. On the same day, Minkow resigned his position as senior pastor, saying in a letter to his flock that because he was no longer "above reproach," he felt that he was "no longer qualified to be a pastor." Six weeks earlier, $50,000 in cash and checks was stolen from the church during a burglary. Though unsolved, it was noted as suspicious due to Minkow's admitted history of staging burglaries to collect insurance money.

The nature of the "nonpublic information" became clear a week later, when federal prosecutors filed a criminal information action against Minkow, with one count of conspiracy to commit securities fraud. Prosecutors charged that Minkow and Marsch conspired to extort money from Lennar by driving down its stock. The complaint also revealed that Minkow had sent his allegations to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and SEC, and that the three agencies found his claims credible enough to open a formal criminal investigation into Lennar's practices. Minkow then used confidential knowledge of that investigation to short Lennar stock, even though he knew he was barred from doing so. Minkow opted to plead guilty to the conspiracy charge rather than face charges of securities fraud and market manipulation, which could have sent him to prison for life.

On March 30, 2011, Minkow pleaded guilty and was eventually sent to jail for five years and ordered to pay Lennar $584 million in damages-roughly the amount the company lost as a result of the bear raid. The ruling stated that Minkow and Marsch had entered into a conspiracy to wreck Lennar's stock in November 2008. With interest, the bill could easily approach $1 billion-far more than he stole in the ZZZZ Best scam.

Questions ( continued )

5. What factors do you think motivated Minkow to return to his evil ways after becoming a respected member of the community following his release from prison in the ZZZZ Best fraud?

6. Using Kohlberg's stages of moral development, how would you characterize Minkow's actions after being released from prison in the ZZZZ Best fraud? Explain the effects of Minkow's actions on the stakeholders who relied on him to act in a professional manner.

1 The facts are derived from a video by the ACFE, Cooking the Books: What Every Accountant Should Know about Fraud.

2 Barry Minkow, Clean Sweep: A Story of Compromise, Corruption, Collapse, and Comeback (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1995).

3 Under current SEC rules, Item 4.01 of Form 8-K requires a company to request the former accountant to furnish a letter stating whether the former accountant agrees with the company's statements concerning the reasons for the change. Where the former accountant declines to provide such a letter, the company should indicate that fact in the Form 8-K. The company must file the 8-K report for the change in accountant within five business days of notification.

1. Yes, the auditors should be held liable for failing to discover fraud. This is the duty of auditor to detect and prevent fraud and any failure to detect fraud and reporting to the board of directors will hold them responsible. There must be an effective system of internal controls and an independent audit function for defense against fraud. While conducting audit, it is the ethical and moral duties of an audit professional that auditor must perform his work with due diligence, exercise reasonable care, must be loyal and honest and work in obedience. The auditors applied all the reasonable care and due diligence to find the proper financial accounts of the corporation but failed to do so. E W was loyal towards their work and was abiding all the laws and regulations but when B tries to pull everything off then the auditor did not act against them as they did not want to lose the ZZZZ best account. This shows that auditor should be made liable as he divert from their ethical obligations. 2. There was enough paper work of the accounts of ZZZZ but there were no actual reports of the restoration sites by the previous auditors. The E W wanted to confirm all the revenues and property of the company. When the auditor inspected the restoration sites, they failed to take the reasonable steps to find out the actual papers of the site to check out to whom the site belong. E W also did not want to lose their client because of good accounts of the company. This shows that E W's relationship with ZZZZ influenced the work done on audit. The auditor came to know about some red flags and they have to work to find the true story behind the accounts of the company. Instead, they supported the company to pursue with the illegal accounting and frauds just to have good records with the company. 3. After looking into the data, we can see that there is sudden increase in the volume of sales from the year 1985 to 1986 which is up to three times more than in the year 1985. Not only sales, the current liabilities, cost of goods sold, accounts receivable were also increased three times more than in year 1985. The inquiries must be made regarding the documents, bank account statements and all the revenues that the company has earned in the financial year 1986. However, increase in the sales is normal phenomenon in this process but the enormous increase would be checked properly by the auditors honestly with due diligence. 4. The fraud triangle describes three conditions requires to be present when fraud occurs. The conditions are as follows:

a. Incentive/ pressure

b. Opportunity

c. Rationalization. The sum up of all these condition is that when the employee has an incentive or pressure then this provides an opportunity to commit fraud or act as a perpetrator. Those involved employee are able to rationalize committing a fraudulent act. In this case, B received incentives for work as carpet cleaner. He has the pressure to become the multi millionaire and started with a fiction idea of insurance restoration job. The opportunity to execute its plan was given by the bank process of clearing the checks. From there B got an idea to kite checks. B started working on the fraud ideas over the phone with the banks to obtain loans by falsifying accounts and revenue. B found one way from another to fraud banks, auditors and other third parties. 5. The Min started working as fraud detector and became the senior pastor after releasing from the jail. But his work of fraud detector provides him the opportunity to involve into the evil ways of fraud. When Min finds the fraud of L, he told Mar about it. Mar then instituted the lawsuit against L which results into the decline in the value of the share of his company. Min bets on the fall in stock and also forged the document to allege the misconduct upon the L in order to win the bet. This betting provides him the opportunity. 6. Kohlberg has six stages of moral development. They are as follows:

i. Obedience and punishment orientation. ii. Self interest orientation. iii. Interpersonal accord and conformity. iv. Authority and social order maintaining orientation. v. Social contract orientation. vi. Universal ethical principles. Min's action after being released from the jail is similar to the stage two of the K's stages of moral development. Stage two is the self interest orientation which means that individual is only concerned about himself and little care about the needs of other. Similarly is the case of Min, who only cares about his money and earnings and does not care about the other's loss because of his behavior as he done to the L. Min fraudulently forged the document to allege fraud against the Lennar in order to win the bet in which huge amount was involved. This shows that Min's behavior satisfied the second stage of moral development.

a. Incentive/ pressure

b. Opportunity

c. Rationalization. The sum up of all these condition is that when the employee has an incentive or pressure then this provides an opportunity to commit fraud or act as a perpetrator. Those involved employee are able to rationalize committing a fraudulent act. In this case, B received incentives for work as carpet cleaner. He has the pressure to become the multi millionaire and started with a fiction idea of insurance restoration job. The opportunity to execute its plan was given by the bank process of clearing the checks. From there B got an idea to kite checks. B started working on the fraud ideas over the phone with the banks to obtain loans by falsifying accounts and revenue. B found one way from another to fraud banks, auditors and other third parties. 5. The Min started working as fraud detector and became the senior pastor after releasing from the jail. But his work of fraud detector provides him the opportunity to involve into the evil ways of fraud. When Min finds the fraud of L, he told Mar about it. Mar then instituted the lawsuit against L which results into the decline in the value of the share of his company. Min bets on the fall in stock and also forged the document to allege the misconduct upon the L in order to win the bet. This betting provides him the opportunity. 6. Kohlberg has six stages of moral development. They are as follows:

i. Obedience and punishment orientation. ii. Self interest orientation. iii. Interpersonal accord and conformity. iv. Authority and social order maintaining orientation. v. Social contract orientation. vi. Universal ethical principles. Min's action after being released from the jail is similar to the stage two of the K's stages of moral development. Stage two is the self interest orientation which means that individual is only concerned about himself and little care about the needs of other. Similarly is the case of Min, who only cares about his money and earnings and does not care about the other's loss because of his behavior as he done to the L. Min fraudulently forged the document to allege fraud against the Lennar in order to win the bet in which huge amount was involved. This shows that Min's behavior satisfied the second stage of moral development.

4

Distinguish between an auditor's responsibilities to detect and report errors, illegal acts, and fraud. What role does materiality have in determining the proper reporting and disclosure of such events?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 30 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

5

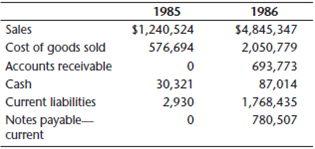

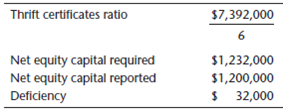

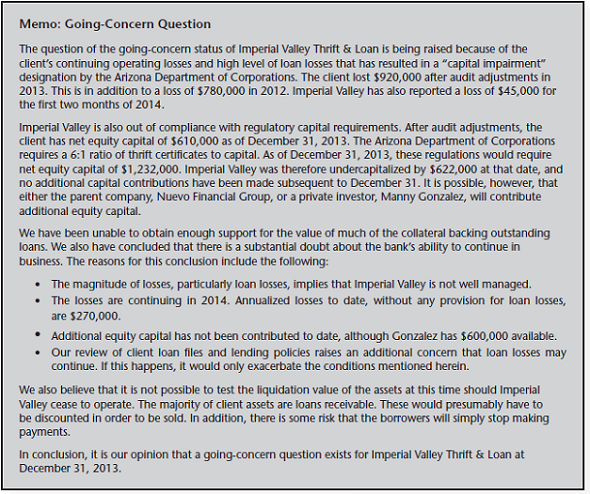

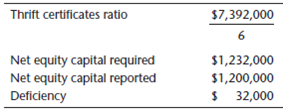

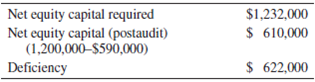

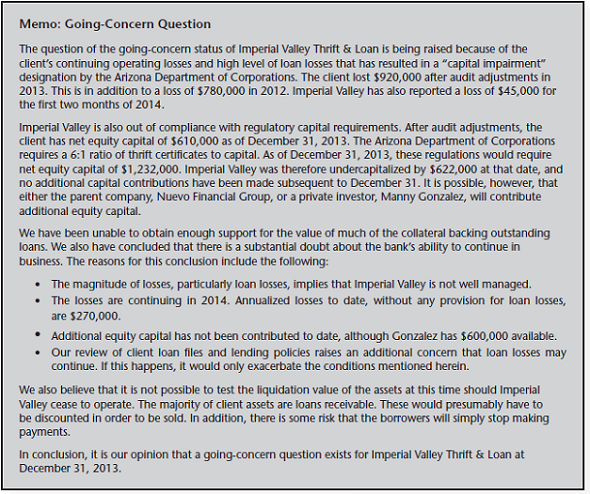

Imperial Valley Thrift Loan

Bill Stanley, of Jacobs, Stanley Company, started to review the working paper files on his client, Imperial Valley Thrift Loan, in preparation for the audit of the client's financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2013. The bank was owned by a parent company, Nuevo Financial Group, and it serviced a small western Arizona community near Yuma that reached south to the border of Mexico. The bank's preaudit statements are presented in Exhibit 1.

Bill Stanley knew there were going to be some problems to contend with during the course of the audit, so he decided to review several items in the file in order to refresh his memory about the client's operations.

Background

The first item Stanley reviewed was the planning memo that he had prepared about two months earlier. This memo is summarized in Exhibit 2.

The next item he reviewed was an internal office communication on potential audit risks. This communication described three areas of particular concern:

1. The client charged off $420,000 in loans in 2012 and had already charged off $535,000 through July 31, 2013. Assuming that reserve requirements by law are a minimum of 1.25 percent of loans outstanding, this statutory amount probably would not be large enough for the loan loss reserve. This, in combination with the prior auditors' concerns about proper loan underwriting procedures and documentation, indicates that the audit engagement team should carefully review loan quality.

2. The audit report issued on the 2012 financial statements contained an unmodified opinion with an emphasis-of- matter paragraph describing the uncertainty about the client's ability to continue as a going concern. The concern was caused by the "capital impairment" declaration by the Arizona Department of Corporations.

3. The client had weak internal controls according to the prior auditors. Some of the items to look out for, in addition to proper loan documentation, were whether the preaudit financial statement information provided by the client was supported by the general ledger, whether the accruals were appropriate, and whether all transactions were properly authorized and recorded on a timely basis.

Audit Findings

Stanley conducted the audit during January and February 2014. Based on information gathered during the audit, the following were the areas of greatest concern to him:

1. Adequacy of Loan Collateral. A review of 30 loan files representing $2,100,000 of total loans outstanding (33.3 percent of the portfolio) indicated that much of the collateral for the loans was in the form of second or third mortgages on real property. This gave the client a potentially unenforceable position due to the existence of very large senior liens. For example, if foreclosure became necessary to collect Imperial Valley's loan, the client would have to pay off these large senior liens first. Other collateral often consisted of personal items such as jewelry and furniture. In the case of jewelry, often there was no effort made by the client after granting the loan to ascertain whether the collateral was still in the possession of the borrower. The jewelry could have been sold without the client's knowledge. It was difficult to obtain sufficient audit evidence about these amounts.

2. Collectibility of Loans. Many loans were structured in such a way as to require interest payments only for a small number of years (two or three years), with a balloon payment for principal due at the end of this time. This structure made it difficult to evaluate the payment history of the borrower properly. Although the annual interest payments may have been made for the first year or two, this was not necessarily a good indication that the borrower would come up with the cash needed to make the large final payment, and the financial statements provided no additional disclosures about this matter.

3. Weakness in Internal Controls. Internal control weaknesses were a pervasive concern. The auditors recomputed certain accruals and unearned discounts, confirmed loan and deposit balances, and reconciled the preaudit financial information provided by the client to the general ledger. Some adjustments had to be made as a result of this work. A material weakness in the lending function was identified. Loans were too frequently granted merely because the borrowers were well known to Imperial Valley officials, who believed that they could be counted on to repay their outstanding loans. An ability to repay these loans was based too often on "faith" rather than on clear indications that the borrowers would have the necessary cash available to repay their loans when they came due. This was of great concern to the auditors, especially in light of the inadequacy of the loan reserve, as detailed in item 5 that follows.