Deck 21: Setting Prices

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

سؤال

فتح الحزمة

قم بالتسجيل لفتح البطاقات في هذه المجموعة!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/34

العب

ملء الشاشة (f)

Deck 21: Setting Prices

1

Price skimming and penetration pricing are strategies that are commonly used to set the base price of a new product. Which strategy is more appropriate for the following products? Explain.

a. Short airline flights between cities in Florida

b. A Blu-ray player

c. A backpack or book bag with a lifetime warranty

d. Season tickets for a newly franchised NBA basketball team

a. Short airline flights between cities in Florida

b. A Blu-ray player

c. A backpack or book bag with a lifetime warranty

d. Season tickets for a newly franchised NBA basketball team

Price skimming: When a company launch a new product, they adopt price skimming as the pricing strategy that focuses on maximizing the profits.

Penetration pricing: It is termed as a marketing technique where the company launch its new product at a price which is lower than what his competitors set. The company starts to increase the price of its product after it has gained customer base and large market share.

(a)Short airline flights between cities in Florida: Penetration pricing is used because here the marketers suspect that the competitors can enter the market easily. The airlines basically schedule the flights with some premium ticket price. As the journey date comes closer, the price of the tickets becomes cheaper so as to attract the customers. Airline makes no money if the seats are empty, while the loss to them of selling the tickets at reduced prices costs very little.

(b)A high definition DVD player: This is an example of price skimming, as when the DVD player is launched premium is being charged and near the end of its life cycle, the lowest prices are being charged.

(c)A backpack or book bag with a lifetime warranty: This is an example of price skimming, when the bags are launched a premium price is being charged and towards the end of its life cycle the lowest prices are being charged.

(d)Season tickets for a newly franchised NBA basketball: This is an example of penetration pricing. The NBA basketball association charge premium on the price of the ticket. As the date of the event comes closer, the association reduces the price of the customers to attract the customers. NBA basketball association will make no money if the seats are empty on the day of the event, while the loss to them of selling the tickets at reduced prices costs very little.

Penetration pricing: It is termed as a marketing technique where the company launch its new product at a price which is lower than what his competitors set. The company starts to increase the price of its product after it has gained customer base and large market share.

(a)Short airline flights between cities in Florida: Penetration pricing is used because here the marketers suspect that the competitors can enter the market easily. The airlines basically schedule the flights with some premium ticket price. As the journey date comes closer, the price of the tickets becomes cheaper so as to attract the customers. Airline makes no money if the seats are empty, while the loss to them of selling the tickets at reduced prices costs very little.

(b)A high definition DVD player: This is an example of price skimming, as when the DVD player is launched premium is being charged and near the end of its life cycle, the lowest prices are being charged.

(c)A backpack or book bag with a lifetime warranty: This is an example of price skimming, when the bags are launched a premium price is being charged and towards the end of its life cycle the lowest prices are being charged.

(d)Season tickets for a newly franchised NBA basketball: This is an example of penetration pricing. The NBA basketball association charge premium on the price of the ticket. As the date of the event comes closer, the association reduces the price of the customers to attract the customers. NBA basketball association will make no money if the seats are empty on the day of the event, while the loss to them of selling the tickets at reduced prices costs very little.

2

JCP Switches to EDLP

When Ron Johnson left Apple to become CEO of JCPenney in late 2011, he discovered that the department store had been running 590 different promotions every year, counting sales, discounts, coupons, clearance events, and other price reductions. But years of competing on price-like so many of its competitors-hadn't done very much to boost JCPenney's revenue or profits. Worse, research showed that customers were shopping at its stores only four times a year. "We haven't given the customer enough reasons to love us," he remembers thinking.

Digging deeper into the company's history, Johnson learned that the founder, James Cash Penney, was well known for his "fair and square" dealings with customers. That became the starting point for the company's switch to everyday low pricing. "People are disgusted with the lack of integrity on pricing," Johnson explained, referring to the retailing industry's reliance on price promotions to attract customers, especially during holiday shopping periods.

Starting in 2012, JCPenney set the price of all merchandise about 40 percent lower than the regular price charged in 2011, a "fair and square" everyday price. This new price policy didn't entirely eliminate price reductions. For example, the retailer planned 12 "month-long values" sales to bring customers into its 1,100 stores every month. It also publicized its first and third Fridays as the days when slow-moving products would be marked down for clearance at the "best" prices. JCPenney began using its Facebook page to prove how "fair and square" its everyday low prices really are by contrasting the "before" and "after" prices of specific items.

Price isn't the only part of JCPenney's marketing mix that's being overhauled. The company now has a new logo, a red-outlined square with the initials "jcp" in one corner, updating the image and echoing the "fair and square" pricing approach. The retailer is also renovating its stores to reflect a "town square" layout of 80 to 100 boutiques and adding new designer product lines to call attention to the company's transformation. For customers who want to shop or browse without going to a store, JCPenney continues to promote its extensive online offerings as well as its apps for cell-phone users. Instead of weekly sales fliers, it mails monthly catalogs featuring merchandise for men, women, children, and the home. The products, not the prices, are the stars of these magazine-like catalogs.

"We want to be the favorite store for everyone, for all Americans, rich and poor, young and old," the CEO says. To do that, JCPenney will have to convince customers that its everyday low prices are fair, compared with the bewildering barrage of coupons and sales that other department stores offer to bargain-hunters. It will also have to make its department stores as appealing as possible, with brand-name products that customers recognize and want to buy-from JCPenney.

What is JCPenney doing to influence the target market's evaluation of the value of its merchandise?

When Ron Johnson left Apple to become CEO of JCPenney in late 2011, he discovered that the department store had been running 590 different promotions every year, counting sales, discounts, coupons, clearance events, and other price reductions. But years of competing on price-like so many of its competitors-hadn't done very much to boost JCPenney's revenue or profits. Worse, research showed that customers were shopping at its stores only four times a year. "We haven't given the customer enough reasons to love us," he remembers thinking.

Digging deeper into the company's history, Johnson learned that the founder, James Cash Penney, was well known for his "fair and square" dealings with customers. That became the starting point for the company's switch to everyday low pricing. "People are disgusted with the lack of integrity on pricing," Johnson explained, referring to the retailing industry's reliance on price promotions to attract customers, especially during holiday shopping periods.

Starting in 2012, JCPenney set the price of all merchandise about 40 percent lower than the regular price charged in 2011, a "fair and square" everyday price. This new price policy didn't entirely eliminate price reductions. For example, the retailer planned 12 "month-long values" sales to bring customers into its 1,100 stores every month. It also publicized its first and third Fridays as the days when slow-moving products would be marked down for clearance at the "best" prices. JCPenney began using its Facebook page to prove how "fair and square" its everyday low prices really are by contrasting the "before" and "after" prices of specific items.

Price isn't the only part of JCPenney's marketing mix that's being overhauled. The company now has a new logo, a red-outlined square with the initials "jcp" in one corner, updating the image and echoing the "fair and square" pricing approach. The retailer is also renovating its stores to reflect a "town square" layout of 80 to 100 boutiques and adding new designer product lines to call attention to the company's transformation. For customers who want to shop or browse without going to a store, JCPenney continues to promote its extensive online offerings as well as its apps for cell-phone users. Instead of weekly sales fliers, it mails monthly catalogs featuring merchandise for men, women, children, and the home. The products, not the prices, are the stars of these magazine-like catalogs.

"We want to be the favorite store for everyone, for all Americans, rich and poor, young and old," the CEO says. To do that, JCPenney will have to convince customers that its everyday low prices are fair, compared with the bewildering barrage of coupons and sales that other department stores offer to bargain-hunters. It will also have to make its department stores as appealing as possible, with brand-name products that customers recognize and want to buy-from JCPenney.

What is JCPenney doing to influence the target market's evaluation of the value of its merchandise?

JCPenney has adopted everyday low price concept to influence the customer and make the customer realize that every day low price is distinctive from any other form of sales that various departmental stores adopt.

It also has brought in an unique way of mailing its magazine like merchandise catalogs through mails without the price.

JCPenney's merchandise, therefore, are evaluated by customers without considering the price and that matters a lot in adding value to its merchandise successfully.

Apart from this it has now made a logo looking good and new and a red-outlines square with its initial "jcp".

It also has brought in an unique way of mailing its magazine like merchandise catalogs through mails without the price.

JCPenney's merchandise, therefore, are evaluated by customers without considering the price and that matters a lot in adding value to its merchandise successfully.

Apart from this it has now made a logo looking good and new and a red-outlines square with its initial "jcp".

3

Identify the six stages in the process of establishing prices.

Six stages in the process of establishing prices:

1. Development of the pricing objectives:

• Pricing objectives are defined as the goals which states what the organization wants to attain through pricing.

• The basis for making decision for other stages of pricing.

• It is essential to be consistent with the organization's overall marketing objectives.

• Both short-term and long-term multiple objectives are used.

2. Target market's evaluation of price:

• The importance of price is dependent on the type of target market, product and the situation when the product is purchased.

• The attributes of the price and quality of the product are combined.

• The customers distinguish among the competing brands.

3. Evaluation of competitor's pricing information:

• The comparative shoppers are the source of competitor's pricing information, defined as people who collect the data systematically based on the competitor's prices.

• The importance of price to the customers is determined.

• It helps the marketers in setting the appropriate and competitive prices for their products.

4. Selection of a basis for pricing:

• The prices are based on the dimensions of demand, competition and cost.

• The selection of a basis for pricing to use id affected by the structure of the market of the industry, the characteristics of the customers, the type of the product and the market share of the brand corresponding to competing brands.

5. Selection of a pricing strategy :

• It is termed as a course of action designed to attain the marketing and pricing objectives.

• Differential pricing comprises of:

• Pricing for Secondary market- Different markets having different prices.

• Negotiated pricing- Bargaining

• Random discounting- Unsystematic

• Periodic discounting- Systematic

• The pricing of new products consists of:

• Price skimming - Starting with high price

• Penetration pricing - Starting with low price

6. Determination of specific price:

• The manner in which pricing is used in marketing mix affects the final value of the product.

• For making adjustments in the marketing mix, the pricing is convenient and flexible.

1. Development of the pricing objectives:

• Pricing objectives are defined as the goals which states what the organization wants to attain through pricing.

• The basis for making decision for other stages of pricing.

• It is essential to be consistent with the organization's overall marketing objectives.

• Both short-term and long-term multiple objectives are used.

2. Target market's evaluation of price:

• The importance of price is dependent on the type of target market, product and the situation when the product is purchased.

• The attributes of the price and quality of the product are combined.

• The customers distinguish among the competing brands.

3. Evaluation of competitor's pricing information:

• The comparative shoppers are the source of competitor's pricing information, defined as people who collect the data systematically based on the competitor's prices.

• The importance of price to the customers is determined.

• It helps the marketers in setting the appropriate and competitive prices for their products.

4. Selection of a basis for pricing:

• The prices are based on the dimensions of demand, competition and cost.

• The selection of a basis for pricing to use id affected by the structure of the market of the industry, the characteristics of the customers, the type of the product and the market share of the brand corresponding to competing brands.

5. Selection of a pricing strategy :

• It is termed as a course of action designed to attain the marketing and pricing objectives.

• Differential pricing comprises of:

• Pricing for Secondary market- Different markets having different prices.

• Negotiated pricing- Bargaining

• Random discounting- Unsystematic

• Periodic discounting- Systematic

• The pricing of new products consists of:

• Price skimming - Starting with high price

• Penetration pricing - Starting with low price

6. Determination of specific price:

• The manner in which pricing is used in marketing mix affects the final value of the product.

• For making adjustments in the marketing mix, the pricing is convenient and flexible.

4

Setting the right price for a product is a crucial part of a marketing strategy. Price helps to establish a product's position in the mind of the consumer and can differentiate a product from its competition. Several decisions in the marketing plan will be affected by the pricing strategy that is selected. To assist you in relating the information in this chapter to the development of your marketing plan, focus on the following:

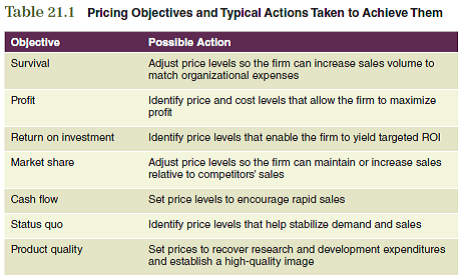

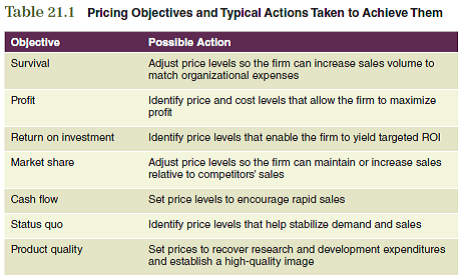

Using Table 21.1 as a guide, discuss each of the seven pricing objectives. Which pricing objectives will you use for your product? Consider the product life cycle, competition, and product positioning for your target market during your discussion.

The information obtained from these questions should assist you in developing various aspects of your marketing plan found in the "Interactive Marketing Plan" exercise at www.cengagebrain.com.

Using Table 21.1 as a guide, discuss each of the seven pricing objectives. Which pricing objectives will you use for your product? Consider the product life cycle, competition, and product positioning for your target market during your discussion.

The information obtained from these questions should assist you in developing various aspects of your marketing plan found in the "Interactive Marketing Plan" exercise at www.cengagebrain.com.

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

5

T-Mobile

T-Mobile has attempted to position itself as a low-cost cellular phone service provider. A person can purchase a calling plan, a cellular phone, and phone accessories at its website.

Visit the company's website at www.t-mobile.com.

Determine the various nationwide calling rates available in your city.

T-Mobile has attempted to position itself as a low-cost cellular phone service provider. A person can purchase a calling plan, a cellular phone, and phone accessories at its website.

Visit the company's website at www.t-mobile.com.

Determine the various nationwide calling rates available in your city.

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

6

Newspapers Test Pricing for Digital Editions

Pricing is one of the most difficult challenges facing U.S. newspapers in the 21st century. The entire industry is feeling a tremendous financial squeeze. Revenues from display advertising have plummeted as many marketers engage customers via social media, Internet ads, special events, daily deal sites, and other promotional methods that sidestep newspapers. Just as important, revenues from paid classified ads have also slumped. Instead of buying classified ads to fill job openings, sell new or used cars, and sell or trade household items, large numbers of consumers and businesses are turning to auction websites, online employment sites, and social media sites.

Looking at trends in paid newspaper subscriptions, the news isn't much better. During the first decade of this century, weekday newspaper circulation fell by 17 percent, and the outlook for a turnaround in print subscriptions is not positive. One reason is that some people- younger consumers, in particular- prefer to get their news online or from television. With the rise of mobile devices like smartphones, tablet computers, and e-book readers, on-the-go consumers have a quick and easy way to click for news, at any time and from any place. The printed newspaper doesn't have the very latest news-but online sources do. Another reason is that many cash-strapped subscribers have cut back on buying newspapers, either because they're worried about their jobs or because they're saving money for other purchases.

In short, newspapers simply can't continue to do business as they did in the last century and expect to prosper in this century. Once-strong newspapers like the Rocky Mountain News have been forced to shut down, while others (like the Christian Science Monitor) have abandoned print in favor of online-only editions. Now, with fewer paying customers and fewer advertisers, newspapers are taking a long, hard look at their pricing strategies to find new ways of improving circulation revenues and profits in the digital age. Some newspapers continue to offer news for free, on the basis that this builds their brands online and offers extra value to readers who want to see updated news whenever it breaks. Other newspapers are trying a paywall, allowing only paid subscribers to see online content that's "walled off" to prevent free access.

Pricing the Digital Wall Street Journal

How do you price the online version of a print newspaper for readers? Should the Internet or mobile edition be entirely free because there are no print costs? Should it be free to customers who subscribe to the print edition? Should some content be free and some fee-only? Or should you set a price for reading almost anything other than today's headlines?

The Wall Street Journal was one of the first newspapers to confront these questions and try to find pricing approaches that made sense for its situation. A national newspaper that's heavy on U.S. and international business news, the Journal also covers general news and politics, economics, investment issues, the arts, and lifestyle trends. Many of its subscribers are professionals, investors, or businesspeople who need to follow the latest happenings in their field and stay updated on world events. During the mid-1990s, the Journal recognized that it had an unusual opportunity to pioneer a new pricing strategy for online news content. It started with a free website, quickly attracted 600,000 registered users, and within a few months, it announced a change to subscriber pricing. Once the site set its prices at $49 per year for online-only access and $29 for print subscribers who wanted to view online material, only 5 percent of the registered users chose to pay for access.

The Journal was prepared for this kind of response. Whereas other newspapers were testing prices for individual articles or for weekly access, the Journal believed it offered subscribers long-term value that they wouldn't appreciate if they could pay for content by the article or by the week. "It's easier for people to see the total value of a package if you have to pay for it all," said the online editor. Giving business readers a comprehensive overview of global markets day after day means "we're not a news site, we're a competitive advantage tool," said another Journal executive.

Despite the steep drop in visitors after the Journal began selling subscriptions, the site had 100,000 paid subscribers within a year. Within two years, it had 200,000 paid subscribers and was nearly at the break-even point. Since then, the Journal has increased its online subscription prices and instituted subscription pricing for access via apps on mobile devices. Today, the newspaper has more than 500,000 digital subscribers, including 80,000 who access the online edition by phone, tablet, or e-book reader. Non-subscribers have access to a limited amount of the Journal's online content, and new-subscriber deals encourage people to sign up rather than be casual visitors. Thanks to the Journal site's loyal and lucrative subscriber base, a growing number of major advertisers are willing to pay to reach this audience online, which contributes millions more to the newspaper's bottom line.

Pricing Digital Versions of Gannett Newspapers

Unlike The Wall Street Journal, which attracts many business readers, Gannett newspapers are for the general public. In addition to USA Today, its national newspaper, Gannett also owns 80 other papers in 30 states. No two of these local papers are exactly alike: some (like the Indianapolis Star in Indianapolis, Indiana) serve big cities, while others (like the Times Recorder in Zanesville, Ohio) serve smaller communities. In recent years, Gannett's circulation revenue has been dropping, and the company has decided to increase revenue by instituting monthly subscription pricing for the digital versions of its local newspapers. USA Today was not included in this new pricing strategy, because of its national distribution.

To start, Gannett tested pricing for online access to three of its local newspaper sites to learn about "consumer engagement and willingness to pay for unique local content," says a spokesperson. Based on the results of those tests, which included full access via computer and mobile devices, Gannett then announced that 80 of its local papers would limit non-subscriber access to digital content. Each local paper was responsible for setting the price, following the general principle that non-subscribers could view no more than 15 articles per month (or as few as five if the paper wants to be more restrictive). To view more content, consumers could choose a monthly subscription for digital-only access using a wide range of devices or a monthly subscription combining print and digital access. Even subscribing to Sunday-only editions will be sufficient to qualify for digital access, if a local paper chooses to price content in that way.

Will consumers pay for digital versions of local newspapers? Some experts believe that local residents will pay for in-depth local coverage and the very latest news, which they can't easily get for free from other sources. If consumers like to read a particular columnist or a regular feature that only appears in the local paper, they will have to pay to see that content online or in print. With the rapid penetration of tablet computers and smartphones, the ability to access local content digitally is increasingly more appealing than reading a once-a-day newspaper in print. Other experts say that consumers have grown accustomed to unlimited online access over the years, and they won't be receptive to paying for what was previously free. However, if consumers find themselves reaching the preset limit of how many articles they can read online, they may find that it's easier to pay than to have to click around and find the content elsewhere for free.

Gannett expects its new digital pricing strategy to increase revenues by as much as $100 million per year, once the pricing is implemented by all 80 papers. "This is a turning point for us," says an executive. Meanwhile, other local newspapers are testing different ways to price online content, also hoping that subscribers will sign up and then remain loyal. Will paywalls pay off?

When The Wall Street Journal began charging for online access, the number of visitors to its site dropped dramatically and slowly began rising again. What does this suggest about the price elasticity of demand for its products?

Pricing is one of the most difficult challenges facing U.S. newspapers in the 21st century. The entire industry is feeling a tremendous financial squeeze. Revenues from display advertising have plummeted as many marketers engage customers via social media, Internet ads, special events, daily deal sites, and other promotional methods that sidestep newspapers. Just as important, revenues from paid classified ads have also slumped. Instead of buying classified ads to fill job openings, sell new or used cars, and sell or trade household items, large numbers of consumers and businesses are turning to auction websites, online employment sites, and social media sites.

Looking at trends in paid newspaper subscriptions, the news isn't much better. During the first decade of this century, weekday newspaper circulation fell by 17 percent, and the outlook for a turnaround in print subscriptions is not positive. One reason is that some people- younger consumers, in particular- prefer to get their news online or from television. With the rise of mobile devices like smartphones, tablet computers, and e-book readers, on-the-go consumers have a quick and easy way to click for news, at any time and from any place. The printed newspaper doesn't have the very latest news-but online sources do. Another reason is that many cash-strapped subscribers have cut back on buying newspapers, either because they're worried about their jobs or because they're saving money for other purchases.

In short, newspapers simply can't continue to do business as they did in the last century and expect to prosper in this century. Once-strong newspapers like the Rocky Mountain News have been forced to shut down, while others (like the Christian Science Monitor) have abandoned print in favor of online-only editions. Now, with fewer paying customers and fewer advertisers, newspapers are taking a long, hard look at their pricing strategies to find new ways of improving circulation revenues and profits in the digital age. Some newspapers continue to offer news for free, on the basis that this builds their brands online and offers extra value to readers who want to see updated news whenever it breaks. Other newspapers are trying a paywall, allowing only paid subscribers to see online content that's "walled off" to prevent free access.

Pricing the Digital Wall Street Journal

How do you price the online version of a print newspaper for readers? Should the Internet or mobile edition be entirely free because there are no print costs? Should it be free to customers who subscribe to the print edition? Should some content be free and some fee-only? Or should you set a price for reading almost anything other than today's headlines?

The Wall Street Journal was one of the first newspapers to confront these questions and try to find pricing approaches that made sense for its situation. A national newspaper that's heavy on U.S. and international business news, the Journal also covers general news and politics, economics, investment issues, the arts, and lifestyle trends. Many of its subscribers are professionals, investors, or businesspeople who need to follow the latest happenings in their field and stay updated on world events. During the mid-1990s, the Journal recognized that it had an unusual opportunity to pioneer a new pricing strategy for online news content. It started with a free website, quickly attracted 600,000 registered users, and within a few months, it announced a change to subscriber pricing. Once the site set its prices at $49 per year for online-only access and $29 for print subscribers who wanted to view online material, only 5 percent of the registered users chose to pay for access.

The Journal was prepared for this kind of response. Whereas other newspapers were testing prices for individual articles or for weekly access, the Journal believed it offered subscribers long-term value that they wouldn't appreciate if they could pay for content by the article or by the week. "It's easier for people to see the total value of a package if you have to pay for it all," said the online editor. Giving business readers a comprehensive overview of global markets day after day means "we're not a news site, we're a competitive advantage tool," said another Journal executive.

Despite the steep drop in visitors after the Journal began selling subscriptions, the site had 100,000 paid subscribers within a year. Within two years, it had 200,000 paid subscribers and was nearly at the break-even point. Since then, the Journal has increased its online subscription prices and instituted subscription pricing for access via apps on mobile devices. Today, the newspaper has more than 500,000 digital subscribers, including 80,000 who access the online edition by phone, tablet, or e-book reader. Non-subscribers have access to a limited amount of the Journal's online content, and new-subscriber deals encourage people to sign up rather than be casual visitors. Thanks to the Journal site's loyal and lucrative subscriber base, a growing number of major advertisers are willing to pay to reach this audience online, which contributes millions more to the newspaper's bottom line.

Pricing Digital Versions of Gannett Newspapers

Unlike The Wall Street Journal, which attracts many business readers, Gannett newspapers are for the general public. In addition to USA Today, its national newspaper, Gannett also owns 80 other papers in 30 states. No two of these local papers are exactly alike: some (like the Indianapolis Star in Indianapolis, Indiana) serve big cities, while others (like the Times Recorder in Zanesville, Ohio) serve smaller communities. In recent years, Gannett's circulation revenue has been dropping, and the company has decided to increase revenue by instituting monthly subscription pricing for the digital versions of its local newspapers. USA Today was not included in this new pricing strategy, because of its national distribution.

To start, Gannett tested pricing for online access to three of its local newspaper sites to learn about "consumer engagement and willingness to pay for unique local content," says a spokesperson. Based on the results of those tests, which included full access via computer and mobile devices, Gannett then announced that 80 of its local papers would limit non-subscriber access to digital content. Each local paper was responsible for setting the price, following the general principle that non-subscribers could view no more than 15 articles per month (or as few as five if the paper wants to be more restrictive). To view more content, consumers could choose a monthly subscription for digital-only access using a wide range of devices or a monthly subscription combining print and digital access. Even subscribing to Sunday-only editions will be sufficient to qualify for digital access, if a local paper chooses to price content in that way.

Will consumers pay for digital versions of local newspapers? Some experts believe that local residents will pay for in-depth local coverage and the very latest news, which they can't easily get for free from other sources. If consumers like to read a particular columnist or a regular feature that only appears in the local paper, they will have to pay to see that content online or in print. With the rapid penetration of tablet computers and smartphones, the ability to access local content digitally is increasingly more appealing than reading a once-a-day newspaper in print. Other experts say that consumers have grown accustomed to unlimited online access over the years, and they won't be receptive to paying for what was previously free. However, if consumers find themselves reaching the preset limit of how many articles they can read online, they may find that it's easier to pay than to have to click around and find the content elsewhere for free.

Gannett expects its new digital pricing strategy to increase revenues by as much as $100 million per year, once the pricing is implemented by all 80 papers. "This is a turning point for us," says an executive. Meanwhile, other local newspapers are testing different ways to price online content, also hoping that subscribers will sign up and then remain loyal. Will paywalls pay off?

When The Wall Street Journal began charging for online access, the number of visitors to its site dropped dramatically and slowly began rising again. What does this suggest about the price elasticity of demand for its products?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

7

Pricing at the Farmers' Market

Whether they're outside the barn or inside the city limits, farmers' markets are becoming more popular as consumers increasingly seek out fresh and local foods. Today, more than 7,000 farmers' markets are open in the United States, selling farm products year-round or only in season. Although some are located within a short drive of the farms where the fruits and vegetables are grown, many operate only on weekends, setting up stands in town squares and city parks to offer a combination of shopping and entertainment. "These markets are establishing themselves as part of our culture in ways that they didn't used to be, and that bodes well for their continued growth," says the director of Local-Harvest. org, which produces a national directory of farmers' markets.

Selling directly to the public enables farmers to build relationships with local shoppers and encourage repeat buying week after week as different items are harvested. It also allows farmers to realize a larger profit margin than if they sold to wholesalers and retailers. This is because the price at which intermediaries buy must have enough room for them to earn a profit when they resell to a store or to consumers. Farmers who market to consumers without intermediaries can charge almost as much-or sometimes even more than-consumers would pay in a supermarket. In many cases, consumers are willing to pay a higher price for top-quality local products, and even more for products that have been certified organic by a recognized authority. Competition is a factor, however. Consumers who browse the farmer's market will quickly see the range of prices that farmers are charging that day for peppers, peaches, or pumpkins. Competition between farmer's markets is another issue, as a new crop of markets appears every season.

Urban Farmz, like other vendors, is adding unique and complementary merchandise to its traditional lineup of agricultural items. Diversifying by selling certified organic soap at its stand, online, and to wholesale accounts will "juice up the brand," as Caleb says. The producers of the organic soap sell it for $14 per bar on their own website, and they ask Urban Farmz to avoid any conflict by selling at a higher price. Thinking fast, Caleb suggests a retail price of $15.95 per bar, saying that this will give Urban Farmz a reasonable profit margin.

Will buyers accept this price? It's time for some competitive homework. The lavender-lemon verbena scent is very popular, and certified-organic products have cachet. Caleb thinks that visitors to the Urban Farmz website will probably not click away to save a dollar or two by buying elsewhere, because then they'll have to pay the other site's shipping fee, as well as the Urban Farmz site's shipping fee. Urban Farmz will also have to set a separate wholesale price when it sells the soap to local restaurants. Will this new soap be the product that boosts Urban Farmz's profits and turns the name into a lifestyle brand?

In the pursuit of profits, how might Urban Farmz use a combination of cost-based, demand-based, and competition-based pricing for the products it sells? Explain your answer.

Whether they're outside the barn or inside the city limits, farmers' markets are becoming more popular as consumers increasingly seek out fresh and local foods. Today, more than 7,000 farmers' markets are open in the United States, selling farm products year-round or only in season. Although some are located within a short drive of the farms where the fruits and vegetables are grown, many operate only on weekends, setting up stands in town squares and city parks to offer a combination of shopping and entertainment. "These markets are establishing themselves as part of our culture in ways that they didn't used to be, and that bodes well for their continued growth," says the director of Local-Harvest. org, which produces a national directory of farmers' markets.

Selling directly to the public enables farmers to build relationships with local shoppers and encourage repeat buying week after week as different items are harvested. It also allows farmers to realize a larger profit margin than if they sold to wholesalers and retailers. This is because the price at which intermediaries buy must have enough room for them to earn a profit when they resell to a store or to consumers. Farmers who market to consumers without intermediaries can charge almost as much-or sometimes even more than-consumers would pay in a supermarket. In many cases, consumers are willing to pay a higher price for top-quality local products, and even more for products that have been certified organic by a recognized authority. Competition is a factor, however. Consumers who browse the farmer's market will quickly see the range of prices that farmers are charging that day for peppers, peaches, or pumpkins. Competition between farmer's markets is another issue, as a new crop of markets appears every season.

Urban Farmz, like other vendors, is adding unique and complementary merchandise to its traditional lineup of agricultural items. Diversifying by selling certified organic soap at its stand, online, and to wholesale accounts will "juice up the brand," as Caleb says. The producers of the organic soap sell it for $14 per bar on their own website, and they ask Urban Farmz to avoid any conflict by selling at a higher price. Thinking fast, Caleb suggests a retail price of $15.95 per bar, saying that this will give Urban Farmz a reasonable profit margin.

Will buyers accept this price? It's time for some competitive homework. The lavender-lemon verbena scent is very popular, and certified-organic products have cachet. Caleb thinks that visitors to the Urban Farmz website will probably not click away to save a dollar or two by buying elsewhere, because then they'll have to pay the other site's shipping fee, as well as the Urban Farmz site's shipping fee. Urban Farmz will also have to set a separate wholesale price when it sells the soap to local restaurants. Will this new soap be the product that boosts Urban Farmz's profits and turns the name into a lifestyle brand?

In the pursuit of profits, how might Urban Farmz use a combination of cost-based, demand-based, and competition-based pricing for the products it sells? Explain your answer.

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

8

Price lining is used to set a limited number of prices for selected lines of merchandise. Visit a few local retail stores to find examples of price lining. For what types of products and stores is this practice most common? For what types of products and stores is price lining not typical or feasible?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

9

JCP Switches to EDLP

When Ron Johnson left Apple to become CEO of JCPenney in late 2011, he discovered that the department store had been running 590 different promotions every year, counting sales, discounts, coupons, clearance events, and other price reductions. But years of competing on price-like so many of its competitors-hadn't done very much to boost JCPenney's revenue or profits. Worse, research showed that customers were shopping at its stores only four times a year. "We haven't given the customer enough reasons to love us," he remembers thinking.

Digging deeper into the company's history, Johnson learned that the founder, James Cash Penney, was well known for his "fair and square" dealings with customers. That became the starting point for the company's switch to everyday low pricing. "People are disgusted with the lack of integrity on pricing," Johnson explained, referring to the retailing industry's reliance on price promotions to attract customers, especially during holiday shopping periods.

Starting in 2012, JCPenney set the price of all merchandise about 40 percent lower than the regular price charged in 2011, a "fair and square" everyday price. This new price policy didn't entirely eliminate price reductions. For example, the retailer planned 12 "month-long values" sales to bring customers into its 1,100 stores every month. It also publicized its first and third Fridays as the days when slow-moving products would be marked down for clearance at the "best" prices. JCPenney began using its Facebook page to prove how "fair and square" its everyday low prices really are by contrasting the "before" and "after" prices of specific items.

Price isn't the only part of JCPenney's marketing mix that's being overhauled. The company now has a new logo, a red-outlined square with the initials "jcp" in one corner, updating the image and echoing the "fair and square" pricing approach. The retailer is also renovating its stores to reflect a "town square" layout of 80 to 100 boutiques and adding new designer product lines to call attention to the company's transformation. For customers who want to shop or browse without going to a store, JCPenney continues to promote its extensive online offerings as well as its apps for cell-phone users. Instead of weekly sales fliers, it mails monthly catalogs featuring merchandise for men, women, children, and the home. The products, not the prices, are the stars of these magazine-like catalogs.

"We want to be the favorite store for everyone, for all Americans, rich and poor, young and old," the CEO says. To do that, JCPenney will have to convince customers that its everyday low prices are fair, compared with the bewildering barrage of coupons and sales that other department stores offer to bargain-hunters. It will also have to make its department stores as appealing as possible, with brand-name products that customers recognize and want to buy-from JCPenney.

How do you think competitors should respond to JCPenney's everyday low prices? Explain your answer.

When Ron Johnson left Apple to become CEO of JCPenney in late 2011, he discovered that the department store had been running 590 different promotions every year, counting sales, discounts, coupons, clearance events, and other price reductions. But years of competing on price-like so many of its competitors-hadn't done very much to boost JCPenney's revenue or profits. Worse, research showed that customers were shopping at its stores only four times a year. "We haven't given the customer enough reasons to love us," he remembers thinking.

Digging deeper into the company's history, Johnson learned that the founder, James Cash Penney, was well known for his "fair and square" dealings with customers. That became the starting point for the company's switch to everyday low pricing. "People are disgusted with the lack of integrity on pricing," Johnson explained, referring to the retailing industry's reliance on price promotions to attract customers, especially during holiday shopping periods.

Starting in 2012, JCPenney set the price of all merchandise about 40 percent lower than the regular price charged in 2011, a "fair and square" everyday price. This new price policy didn't entirely eliminate price reductions. For example, the retailer planned 12 "month-long values" sales to bring customers into its 1,100 stores every month. It also publicized its first and third Fridays as the days when slow-moving products would be marked down for clearance at the "best" prices. JCPenney began using its Facebook page to prove how "fair and square" its everyday low prices really are by contrasting the "before" and "after" prices of specific items.

Price isn't the only part of JCPenney's marketing mix that's being overhauled. The company now has a new logo, a red-outlined square with the initials "jcp" in one corner, updating the image and echoing the "fair and square" pricing approach. The retailer is also renovating its stores to reflect a "town square" layout of 80 to 100 boutiques and adding new designer product lines to call attention to the company's transformation. For customers who want to shop or browse without going to a store, JCPenney continues to promote its extensive online offerings as well as its apps for cell-phone users. Instead of weekly sales fliers, it mails monthly catalogs featuring merchandise for men, women, children, and the home. The products, not the prices, are the stars of these magazine-like catalogs.

"We want to be the favorite store for everyone, for all Americans, rich and poor, young and old," the CEO says. To do that, JCPenney will have to convince customers that its everyday low prices are fair, compared with the bewildering barrage of coupons and sales that other department stores offer to bargain-hunters. It will also have to make its department stores as appealing as possible, with brand-name products that customers recognize and want to buy-from JCPenney.

How do you think competitors should respond to JCPenney's everyday low prices? Explain your answer.

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

10

How does a return on an investment pricing objective differ from an objective of increasing market share?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

11

Setting the right price for a product is a crucial part of a marketing strategy. Price helps to establish a product's position in the mind of the consumer and can differentiate a product from its competition. Several decisions in the marketing plan will be affected by the pricing strategy that is selected. To assist you in relating the information in this chapter to the development of your marketing plan, focus on the following:

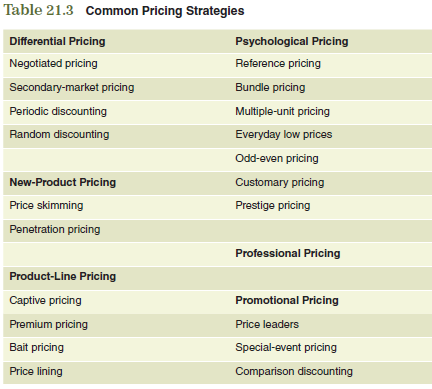

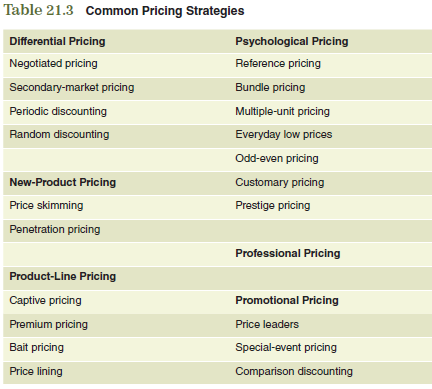

Review the various types of pricing strategies in Table 21.3. Which of these is the most appropriate for your product?

The information obtained from these questions should assist you in developing various aspects of your marketing plan found in the "Interactive Marketing Plan" exercise at www.cengagebrain.com.

Review the various types of pricing strategies in Table 21.3. Which of these is the most appropriate for your product?

The information obtained from these questions should assist you in developing various aspects of your marketing plan found in the "Interactive Marketing Plan" exercise at www.cengagebrain.com.

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

12

T-Mobile

T-Mobile has attempted to position itself as a low-cost cellular phone service provider. A person can purchase a calling plan, a cellular phone, and phone accessories at its website.

Visit the company's website at www.t-mobile.com.

How many different calling plans are available in your area?

T-Mobile has attempted to position itself as a low-cost cellular phone service provider. A person can purchase a calling plan, a cellular phone, and phone accessories at its website.

Visit the company's website at www.t-mobile.com.

How many different calling plans are available in your area?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

13

Newspapers Test Pricing for Digital Editions

Pricing is one of the most difficult challenges facing U.S. newspapers in the 21st century. The entire industry is feeling a tremendous financial squeeze. Revenues from display advertising have plummeted as many marketers engage customers via social media, Internet ads, special events, daily deal sites, and other promotional methods that sidestep newspapers. Just as important, revenues from paid classified ads have also slumped. Instead of buying classified ads to fill job openings, sell new or used cars, and sell or trade household items, large numbers of consumers and businesses are turning to auction websites, online employment sites, and social media sites.

Looking at trends in paid newspaper subscriptions, the news isn't much better. During the first decade of this century, weekday newspaper circulation fell by 17 percent, and the outlook for a turnaround in print subscriptions is not positive. One reason is that some people- younger consumers, in particular- prefer to get their news online or from television. With the rise of mobile devices like smartphones, tablet computers, and e-book readers, on-the-go consumers have a quick and easy way to click for news, at any time and from any place. The printed newspaper doesn't have the very latest news-but online sources do. Another reason is that many cash-strapped subscribers have cut back on buying newspapers, either because they're worried about their jobs or because they're saving money for other purchases.

In short, newspapers simply can't continue to do business as they did in the last century and expect to prosper in this century. Once-strong newspapers like the Rocky Mountain News have been forced to shut down, while others (like the Christian Science Monitor) have abandoned print in favor of online-only editions. Now, with fewer paying customers and fewer advertisers, newspapers are taking a long, hard look at their pricing strategies to find new ways of improving circulation revenues and profits in the digital age. Some newspapers continue to offer news for free, on the basis that this builds their brands online and offers extra value to readers who want to see updated news whenever it breaks. Other newspapers are trying a paywall, allowing only paid subscribers to see online content that's "walled off" to prevent free access.

Pricing the Digital Wall Street Journal

How do you price the online version of a print newspaper for readers? Should the Internet or mobile edition be entirely free because there are no print costs? Should it be free to customers who subscribe to the print edition? Should some content be free and some fee-only? Or should you set a price for reading almost anything other than today's headlines?

The Wall Street Journal was one of the first newspapers to confront these questions and try to find pricing approaches that made sense for its situation. A national newspaper that's heavy on U.S. and international business news, the Journal also covers general news and politics, economics, investment issues, the arts, and lifestyle trends. Many of its subscribers are professionals, investors, or businesspeople who need to follow the latest happenings in their field and stay updated on world events. During the mid-1990s, the Journal recognized that it had an unusual opportunity to pioneer a new pricing strategy for online news content. It started with a free website, quickly attracted 600,000 registered users, and within a few months, it announced a change to subscriber pricing. Once the site set its prices at $49 per year for online-only access and $29 for print subscribers who wanted to view online material, only 5 percent of the registered users chose to pay for access.

The Journal was prepared for this kind of response. Whereas other newspapers were testing prices for individual articles or for weekly access, the Journal believed it offered subscribers long-term value that they wouldn't appreciate if they could pay for content by the article or by the week. "It's easier for people to see the total value of a package if you have to pay for it all," said the online editor. Giving business readers a comprehensive overview of global markets day after day means "we're not a news site, we're a competitive advantage tool," said another Journal executive.

Despite the steep drop in visitors after the Journal began selling subscriptions, the site had 100,000 paid subscribers within a year. Within two years, it had 200,000 paid subscribers and was nearly at the break-even point. Since then, the Journal has increased its online subscription prices and instituted subscription pricing for access via apps on mobile devices. Today, the newspaper has more than 500,000 digital subscribers, including 80,000 who access the online edition by phone, tablet, or e-book reader. Non-subscribers have access to a limited amount of the Journal's online content, and new-subscriber deals encourage people to sign up rather than be casual visitors. Thanks to the Journal site's loyal and lucrative subscriber base, a growing number of major advertisers are willing to pay to reach this audience online, which contributes millions more to the newspaper's bottom line.

Pricing Digital Versions of Gannett Newspapers

Unlike The Wall Street Journal, which attracts many business readers, Gannett newspapers are for the general public. In addition to USA Today, its national newspaper, Gannett also owns 80 other papers in 30 states. No two of these local papers are exactly alike: some (like the Indianapolis Star in Indianapolis, Indiana) serve big cities, while others (like the Times Recorder in Zanesville, Ohio) serve smaller communities. In recent years, Gannett's circulation revenue has been dropping, and the company has decided to increase revenue by instituting monthly subscription pricing for the digital versions of its local newspapers. USA Today was not included in this new pricing strategy, because of its national distribution.

To start, Gannett tested pricing for online access to three of its local newspaper sites to learn about "consumer engagement and willingness to pay for unique local content," says a spokesperson. Based on the results of those tests, which included full access via computer and mobile devices, Gannett then announced that 80 of its local papers would limit non-subscriber access to digital content. Each local paper was responsible for setting the price, following the general principle that non-subscribers could view no more than 15 articles per month (or as few as five if the paper wants to be more restrictive). To view more content, consumers could choose a monthly subscription for digital-only access using a wide range of devices or a monthly subscription combining print and digital access. Even subscribing to Sunday-only editions will be sufficient to qualify for digital access, if a local paper chooses to price content in that way.

Will consumers pay for digital versions of local newspapers? Some experts believe that local residents will pay for in-depth local coverage and the very latest news, which they can't easily get for free from other sources. If consumers like to read a particular columnist or a regular feature that only appears in the local paper, they will have to pay to see that content online or in print. With the rapid penetration of tablet computers and smartphones, the ability to access local content digitally is increasingly more appealing than reading a once-a-day newspaper in print. Other experts say that consumers have grown accustomed to unlimited online access over the years, and they won't be receptive to paying for what was previously free. However, if consumers find themselves reaching the preset limit of how many articles they can read online, they may find that it's easier to pay than to have to click around and find the content elsewhere for free.

Gannett expects its new digital pricing strategy to increase revenues by as much as $100 million per year, once the pricing is implemented by all 80 papers. "This is a turning point for us," says an executive. Meanwhile, other local newspapers are testing different ways to price online content, also hoping that subscribers will sign up and then remain loyal. Will paywalls pay off?

Would consumers have an internal reference price for digital newspaper content? Explain your answer.

Pricing is one of the most difficult challenges facing U.S. newspapers in the 21st century. The entire industry is feeling a tremendous financial squeeze. Revenues from display advertising have plummeted as many marketers engage customers via social media, Internet ads, special events, daily deal sites, and other promotional methods that sidestep newspapers. Just as important, revenues from paid classified ads have also slumped. Instead of buying classified ads to fill job openings, sell new or used cars, and sell or trade household items, large numbers of consumers and businesses are turning to auction websites, online employment sites, and social media sites.

Looking at trends in paid newspaper subscriptions, the news isn't much better. During the first decade of this century, weekday newspaper circulation fell by 17 percent, and the outlook for a turnaround in print subscriptions is not positive. One reason is that some people- younger consumers, in particular- prefer to get their news online or from television. With the rise of mobile devices like smartphones, tablet computers, and e-book readers, on-the-go consumers have a quick and easy way to click for news, at any time and from any place. The printed newspaper doesn't have the very latest news-but online sources do. Another reason is that many cash-strapped subscribers have cut back on buying newspapers, either because they're worried about their jobs or because they're saving money for other purchases.

In short, newspapers simply can't continue to do business as they did in the last century and expect to prosper in this century. Once-strong newspapers like the Rocky Mountain News have been forced to shut down, while others (like the Christian Science Monitor) have abandoned print in favor of online-only editions. Now, with fewer paying customers and fewer advertisers, newspapers are taking a long, hard look at their pricing strategies to find new ways of improving circulation revenues and profits in the digital age. Some newspapers continue to offer news for free, on the basis that this builds their brands online and offers extra value to readers who want to see updated news whenever it breaks. Other newspapers are trying a paywall, allowing only paid subscribers to see online content that's "walled off" to prevent free access.

Pricing the Digital Wall Street Journal

How do you price the online version of a print newspaper for readers? Should the Internet or mobile edition be entirely free because there are no print costs? Should it be free to customers who subscribe to the print edition? Should some content be free and some fee-only? Or should you set a price for reading almost anything other than today's headlines?

The Wall Street Journal was one of the first newspapers to confront these questions and try to find pricing approaches that made sense for its situation. A national newspaper that's heavy on U.S. and international business news, the Journal also covers general news and politics, economics, investment issues, the arts, and lifestyle trends. Many of its subscribers are professionals, investors, or businesspeople who need to follow the latest happenings in their field and stay updated on world events. During the mid-1990s, the Journal recognized that it had an unusual opportunity to pioneer a new pricing strategy for online news content. It started with a free website, quickly attracted 600,000 registered users, and within a few months, it announced a change to subscriber pricing. Once the site set its prices at $49 per year for online-only access and $29 for print subscribers who wanted to view online material, only 5 percent of the registered users chose to pay for access.

The Journal was prepared for this kind of response. Whereas other newspapers were testing prices for individual articles or for weekly access, the Journal believed it offered subscribers long-term value that they wouldn't appreciate if they could pay for content by the article or by the week. "It's easier for people to see the total value of a package if you have to pay for it all," said the online editor. Giving business readers a comprehensive overview of global markets day after day means "we're not a news site, we're a competitive advantage tool," said another Journal executive.

Despite the steep drop in visitors after the Journal began selling subscriptions, the site had 100,000 paid subscribers within a year. Within two years, it had 200,000 paid subscribers and was nearly at the break-even point. Since then, the Journal has increased its online subscription prices and instituted subscription pricing for access via apps on mobile devices. Today, the newspaper has more than 500,000 digital subscribers, including 80,000 who access the online edition by phone, tablet, or e-book reader. Non-subscribers have access to a limited amount of the Journal's online content, and new-subscriber deals encourage people to sign up rather than be casual visitors. Thanks to the Journal site's loyal and lucrative subscriber base, a growing number of major advertisers are willing to pay to reach this audience online, which contributes millions more to the newspaper's bottom line.

Pricing Digital Versions of Gannett Newspapers

Unlike The Wall Street Journal, which attracts many business readers, Gannett newspapers are for the general public. In addition to USA Today, its national newspaper, Gannett also owns 80 other papers in 30 states. No two of these local papers are exactly alike: some (like the Indianapolis Star in Indianapolis, Indiana) serve big cities, while others (like the Times Recorder in Zanesville, Ohio) serve smaller communities. In recent years, Gannett's circulation revenue has been dropping, and the company has decided to increase revenue by instituting monthly subscription pricing for the digital versions of its local newspapers. USA Today was not included in this new pricing strategy, because of its national distribution.

To start, Gannett tested pricing for online access to three of its local newspaper sites to learn about "consumer engagement and willingness to pay for unique local content," says a spokesperson. Based on the results of those tests, which included full access via computer and mobile devices, Gannett then announced that 80 of its local papers would limit non-subscriber access to digital content. Each local paper was responsible for setting the price, following the general principle that non-subscribers could view no more than 15 articles per month (or as few as five if the paper wants to be more restrictive). To view more content, consumers could choose a monthly subscription for digital-only access using a wide range of devices or a monthly subscription combining print and digital access. Even subscribing to Sunday-only editions will be sufficient to qualify for digital access, if a local paper chooses to price content in that way.

Will consumers pay for digital versions of local newspapers? Some experts believe that local residents will pay for in-depth local coverage and the very latest news, which they can't easily get for free from other sources. If consumers like to read a particular columnist or a regular feature that only appears in the local paper, they will have to pay to see that content online or in print. With the rapid penetration of tablet computers and smartphones, the ability to access local content digitally is increasingly more appealing than reading a once-a-day newspaper in print. Other experts say that consumers have grown accustomed to unlimited online access over the years, and they won't be receptive to paying for what was previously free. However, if consumers find themselves reaching the preset limit of how many articles they can read online, they may find that it's easier to pay than to have to click around and find the content elsewhere for free.

Gannett expects its new digital pricing strategy to increase revenues by as much as $100 million per year, once the pricing is implemented by all 80 papers. "This is a turning point for us," says an executive. Meanwhile, other local newspapers are testing different ways to price online content, also hoping that subscribers will sign up and then remain loyal. Will paywalls pay off?

Would consumers have an internal reference price for digital newspaper content? Explain your answer.

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

14

Pricing at the Farmers' Market

Whether they're outside the barn or inside the city limits, farmers' markets are becoming more popular as consumers increasingly seek out fresh and local foods. Today, more than 7,000 farmers' markets are open in the United States, selling farm products year-round or only in season. Although some are located within a short drive of the farms where the fruits and vegetables are grown, many operate only on weekends, setting up stands in town squares and city parks to offer a combination of shopping and entertainment. "These markets are establishing themselves as part of our culture in ways that they didn't used to be, and that bodes well for their continued growth," says the director of Local-Harvest. org, which produces a national directory of farmers' markets.

Selling directly to the public enables farmers to build relationships with local shoppers and encourage repeat buying week after week as different items are harvested. It also allows farmers to realize a larger profit margin than if they sold to wholesalers and retailers. This is because the price at which intermediaries buy must have enough room for them to earn a profit when they resell to a store or to consumers. Farmers who market to consumers without intermediaries can charge almost as much-or sometimes even more than-consumers would pay in a supermarket. In many cases, consumers are willing to pay a higher price for top-quality local products, and even more for products that have been certified organic by a recognized authority. Competition is a factor, however. Consumers who browse the farmer's market will quickly see the range of prices that farmers are charging that day for peppers, peaches, or pumpkins. Competition between farmer's markets is another issue, as a new crop of markets appears every season.

Urban Farmz, like other vendors, is adding unique and complementary merchandise to its traditional lineup of agricultural items. Diversifying by selling certified organic soap at its stand, online, and to wholesale accounts will "juice up the brand," as Caleb says. The producers of the organic soap sell it for $14 per bar on their own website, and they ask Urban Farmz to avoid any conflict by selling at a higher price. Thinking fast, Caleb suggests a retail price of $15.95 per bar, saying that this will give Urban Farmz a reasonable profit margin.

Will buyers accept this price? It's time for some competitive homework. The lavender-lemon verbena scent is very popular, and certified-organic products have cachet. Caleb thinks that visitors to the Urban Farmz website will probably not click away to save a dollar or two by buying elsewhere, because then they'll have to pay the other site's shipping fee, as well as the Urban Farmz site's shipping fee. Urban Farmz will also have to set a separate wholesale price when it sells the soap to local restaurants. Will this new soap be the product that boosts Urban Farmz's profits and turns the name into a lifestyle brand?

Urban Farmz wants to price the organic soap at $15.95 per bar, while the soap maker prices the same soap at $14 per bar. What perceptions do you think consumers will have of each price? What recommendations do you have regarding this price difference?

Whether they're outside the barn or inside the city limits, farmers' markets are becoming more popular as consumers increasingly seek out fresh and local foods. Today, more than 7,000 farmers' markets are open in the United States, selling farm products year-round or only in season. Although some are located within a short drive of the farms where the fruits and vegetables are grown, many operate only on weekends, setting up stands in town squares and city parks to offer a combination of shopping and entertainment. "These markets are establishing themselves as part of our culture in ways that they didn't used to be, and that bodes well for their continued growth," says the director of Local-Harvest. org, which produces a national directory of farmers' markets.

Selling directly to the public enables farmers to build relationships with local shoppers and encourage repeat buying week after week as different items are harvested. It also allows farmers to realize a larger profit margin than if they sold to wholesalers and retailers. This is because the price at which intermediaries buy must have enough room for them to earn a profit when they resell to a store or to consumers. Farmers who market to consumers without intermediaries can charge almost as much-or sometimes even more than-consumers would pay in a supermarket. In many cases, consumers are willing to pay a higher price for top-quality local products, and even more for products that have been certified organic by a recognized authority. Competition is a factor, however. Consumers who browse the farmer's market will quickly see the range of prices that farmers are charging that day for peppers, peaches, or pumpkins. Competition between farmer's markets is another issue, as a new crop of markets appears every season.

Urban Farmz, like other vendors, is adding unique and complementary merchandise to its traditional lineup of agricultural items. Diversifying by selling certified organic soap at its stand, online, and to wholesale accounts will "juice up the brand," as Caleb says. The producers of the organic soap sell it for $14 per bar on their own website, and they ask Urban Farmz to avoid any conflict by selling at a higher price. Thinking fast, Caleb suggests a retail price of $15.95 per bar, saying that this will give Urban Farmz a reasonable profit margin.

Will buyers accept this price? It's time for some competitive homework. The lavender-lemon verbena scent is very popular, and certified-organic products have cachet. Caleb thinks that visitors to the Urban Farmz website will probably not click away to save a dollar or two by buying elsewhere, because then they'll have to pay the other site's shipping fee, as well as the Urban Farmz site's shipping fee. Urban Farmz will also have to set a separate wholesale price when it sells the soap to local restaurants. Will this new soap be the product that boosts Urban Farmz's profits and turns the name into a lifestyle brand?

Urban Farmz wants to price the organic soap at $15.95 per bar, while the soap maker prices the same soap at $14 per bar. What perceptions do you think consumers will have of each price? What recommendations do you have regarding this price difference?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

15

Professional pricing is used by people who have great skill in a particular field, such as doctors, lawyers, and business consultants. Find examples (advertisements, personal contacts) that reflect a professional pricing policy. How is the price established? Are there any restrictions on the services performed at that price?

فتح الحزمة

افتح القفل للوصول البطاقات البالغ عددها 34 في هذه المجموعة.

فتح الحزمة

k this deck

16

JCP Switches to EDLP

When Ron Johnson left Apple to become CEO of JCPenney in late 2011, he discovered that the department store had been running 590 different promotions every year, counting sales, discounts, coupons, clearance events, and other price reductions. But years of competing on price-like so many of its competitors-hadn't done very much to boost JCPenney's revenue or profits. Worse, research showed that customers were shopping at its stores only four times a year. "We haven't given the customer enough reasons to love us," he remembers thinking.

Digging deeper into the company's history, Johnson learned that the founder, James Cash Penney, was well known for his "fair and square" dealings with customers. That became the starting point for the company's switch to everyday low pricing. "People are disgusted with the lack of integrity on pricing," Johnson explained, referring to the retailing industry's reliance on price promotions to attract customers, especially during holiday shopping periods.

Starting in 2012, JCPenney set the price of all merchandise about 40 percent lower than the regular price charged in 2011, a "fair and square" everyday price. This new price policy didn't entirely eliminate price reductions. For example, the retailer planned 12 "month-long values" sales to bring customers into its 1,100 stores every month. It also publicized its first and third Fridays as the days when slow-moving products would be marked down for clearance at the "best" prices. JCPenney began using its Facebook page to prove how "fair and square" its everyday low prices really are by contrasting the "before" and "after" prices of specific items.

Price isn't the only part of JCPenney's marketing mix that's being overhauled. The company now has a new logo, a red-outlined square with the initials "jcp" in one corner, updating the image and echoing the "fair and square" pricing approach. The retailer is also renovating its stores to reflect a "town square" layout of 80 to 100 boutiques and adding new designer product lines to call attention to the company's transformation. For customers who want to shop or browse without going to a store, JCPenney continues to promote its extensive online offerings as well as its apps for cell-phone users. Instead of weekly sales fliers, it mails monthly catalogs featuring merchandise for men, women, children, and the home. The products, not the prices, are the stars of these magazine-like catalogs.

"We want to be the favorite store for everyone, for all Americans, rich and poor, young and old," the CEO says. To do that, JCPenney will have to convince customers that its everyday low prices are fair, compared with the bewildering barrage of coupons and sales that other department stores offer to bargain-hunters. It will also have to make its department stores as appealing as possible, with brand-name products that customers recognize and want to buy-from JCPenney.

Would you suggest that JCPenney reveal the markup it uses to arrive at its prices as a way to convince customers that its everyday prices really are low?

When Ron Johnson left Apple to become CEO of JCPenney in late 2011, he discovered that the department store had been running 590 different promotions every year, counting sales, discounts, coupons, clearance events, and other price reductions. But years of competing on price-like so many of its competitors-hadn't done very much to boost JCPenney's revenue or profits. Worse, research showed that customers were shopping at its stores only four times a year. "We haven't given the customer enough reasons to love us," he remembers thinking.

Digging deeper into the company's history, Johnson learned that the founder, James Cash Penney, was well known for his "fair and square" dealings with customers. That became the starting point for the company's switch to everyday low pricing. "People are disgusted with the lack of integrity on pricing," Johnson explained, referring to the retailing industry's reliance on price promotions to attract customers, especially during holiday shopping periods.