Deck 19: Pricing Concepts

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/10

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 19: Pricing Concepts

1

Reliance on price as a predictor of quality seems to occur for all products. Does this mean that high-priced products are superior? Well, sometimes. Price can be a good predictor of quality for some products, but for others, price is not always the best way to determine the quality of a product or service before buying it. This exercise (and worksheet) will help you examine the price-quality relationship for a simple product: canned goods.

Activities

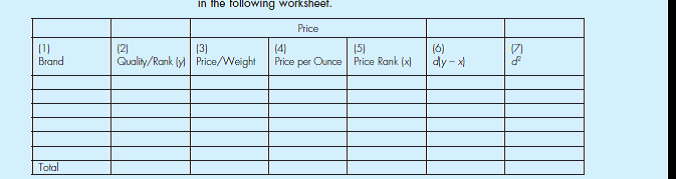

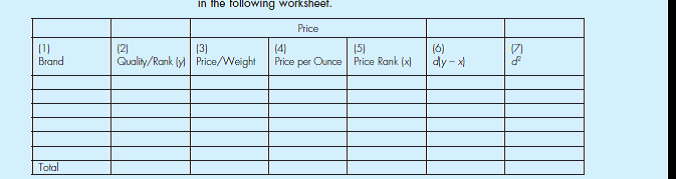

1. Take a trip to a local supermarket where you are certain to find multiple brands of canned fruits and vegetables. Pick a single type of vegetable or fruit you like, such as cream corn or peach halves, and list five or six brands in the following worksheet.

2. Before going any further, rank the brands according to which you think is the highest quality (1) to the lowest quality (5 or 6, depending on how many brands you find). This ranking will be y.

3. Record the price and the volume of each brand. For example, if a 14-ounce can costs $.89, you would list $.89/14 oz.

4. Translate the price per volume into price per ounce. Our 14-ounce can costs $.064 per ounce.

5. Now rank the price per ounce (we'll call it x ) from the highest (1) to the lowest (5 or 6, again depending on how many brands you have).

6. We'll now begin calculating the coefficient of correlation between the price and quality rankings. The first step is to subtract x from y. Enter the result, d , in column 6.

7. Now calculate d 2 and enter the value in column 7. Write the sum of all the entries in column 7 in the final row.

8. The formula for calculating a price-quality coefficient r is as follows: In the formula, r s is the coefficient of correlation, 6 is a constant, and n is the number of items ranked.

9. What does the result of your calculation tell you about the correlation between the price and the quality of the canned vegetable or fruit you selected? Now that you know this, will it change your buying habits?

Activities

1. Take a trip to a local supermarket where you are certain to find multiple brands of canned fruits and vegetables. Pick a single type of vegetable or fruit you like, such as cream corn or peach halves, and list five or six brands in the following worksheet.

2. Before going any further, rank the brands according to which you think is the highest quality (1) to the lowest quality (5 or 6, depending on how many brands you find). This ranking will be y.

3. Record the price and the volume of each brand. For example, if a 14-ounce can costs $.89, you would list $.89/14 oz.

4. Translate the price per volume into price per ounce. Our 14-ounce can costs $.064 per ounce.

5. Now rank the price per ounce (we'll call it x ) from the highest (1) to the lowest (5 or 6, again depending on how many brands you have).

6. We'll now begin calculating the coefficient of correlation between the price and quality rankings. The first step is to subtract x from y. Enter the result, d , in column 6.

7. Now calculate d 2 and enter the value in column 7. Write the sum of all the entries in column 7 in the final row.

8. The formula for calculating a price-quality coefficient r is as follows: In the formula, r s is the coefficient of correlation, 6 is a constant, and n is the number of items ranked.

9. What does the result of your calculation tell you about the correlation between the price and the quality of the canned vegetable or fruit you selected? Now that you know this, will it change your buying habits?

Price - quality correlation:

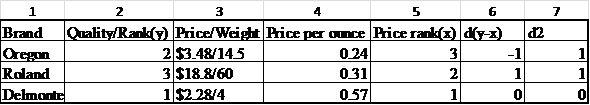

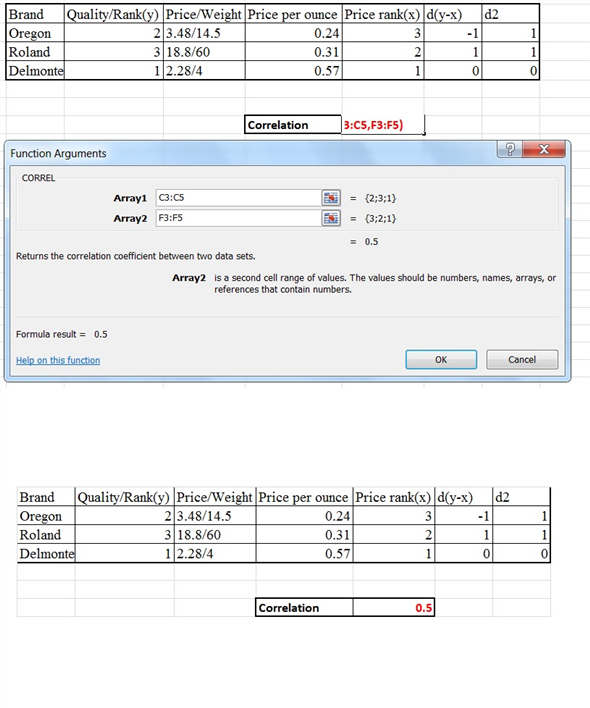

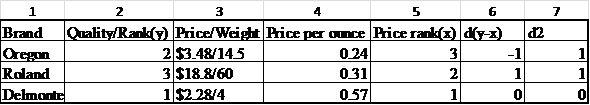

Collect the price and the weight of canned cherries from different brands. The data was represented in the below table.

There are 3 brands of canned cherries Oregon, Roland, and Delmonte. In the second column, there is quality ranking as per our perception. Highest is 1 and lowest is 3. In the third column there is a price weight in ounces is given for each product. In the fourth column price per ounce is calculated and shown;

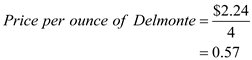

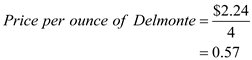

For instance, price per ounce of Delmonte:

Price Rank: Rank the brands as per the price, with 1 st rank going to the highest price per ounce. Therefore, the price per ounce rank is Delmonte, Roland and Oregon respectively.

Price Rank: Rank the brands as per the price, with 1 st rank going to the highest price per ounce. Therefore, the price per ounce rank is Delmonte, Roland and Oregon respectively.

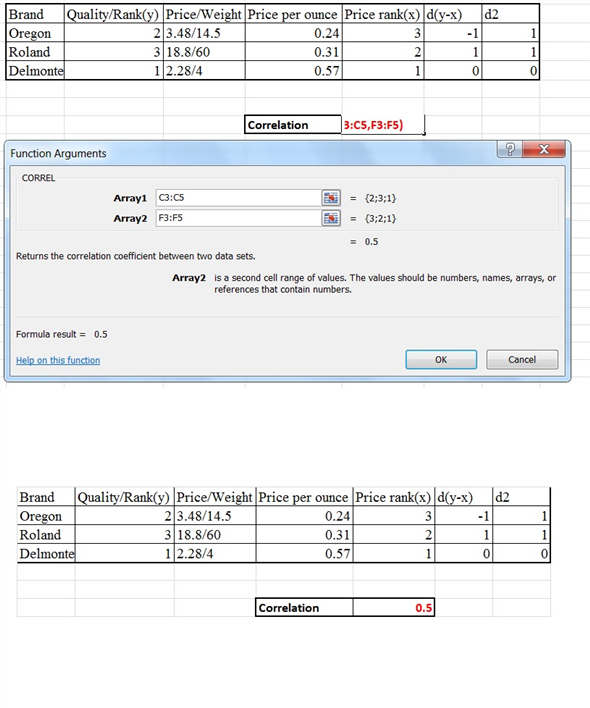

Correlation between price and quality of the canned cherries:

Find correlation between quality perceived and the price per ounce by using the excel as shown below,

We can see that the correlation is only 50% or 0.5. Thus, the quality of the product is not completely dependent on the price. In addition, it is completely misguiding that a higher priced product will come with a higher quality.

We can see that the correlation is only 50% or 0.5. Thus, the quality of the product is not completely dependent on the price. In addition, it is completely misguiding that a higher priced product will come with a higher quality.

Collect the price and the weight of canned cherries from different brands. The data was represented in the below table.

There are 3 brands of canned cherries Oregon, Roland, and Delmonte. In the second column, there is quality ranking as per our perception. Highest is 1 and lowest is 3. In the third column there is a price weight in ounces is given for each product. In the fourth column price per ounce is calculated and shown;

For instance, price per ounce of Delmonte:

Price Rank: Rank the brands as per the price, with 1 st rank going to the highest price per ounce. Therefore, the price per ounce rank is Delmonte, Roland and Oregon respectively.

Price Rank: Rank the brands as per the price, with 1 st rank going to the highest price per ounce. Therefore, the price per ounce rank is Delmonte, Roland and Oregon respectively.Correlation between price and quality of the canned cherries:

Find correlation between quality perceived and the price per ounce by using the excel as shown below,

We can see that the correlation is only 50% or 0.5. Thus, the quality of the product is not completely dependent on the price. In addition, it is completely misguiding that a higher priced product will come with a higher quality.

We can see that the correlation is only 50% or 0.5. Thus, the quality of the product is not completely dependent on the price. In addition, it is completely misguiding that a higher priced product will come with a higher quality. 2

As long as people have stomach aches, companies will sell remedies. Acid+All is banking that America will continue its love affair with bad food and has made an interesting move into the antacid market. The tiny pills come packaged in a tin priced at $3.89, which clearly sets the product apart from competitors like Rolaids, Tums, and others. The gambit of staking out a position as a prestige product is high. Watch the video to see what issues helped forge the $3.89 unit price and if the company has been successful at this price point.

How do the product, place, and promotion elements of Acid+All's marketing mix influence the pricing strategy the company has chosen?

How do the product, place, and promotion elements of Acid+All's marketing mix influence the pricing strategy the company has chosen?

Web Based Activity

Watch the video and determine how the antacid's unique marketing mix creates a place for it in the face of its completion. Observe which elements give the brand an edge and allow it to be marketed as a prestige product.

Watch the video and determine how the antacid's unique marketing mix creates a place for it in the face of its completion. Observe which elements give the brand an edge and allow it to be marketed as a prestige product.

3

On January 20, 2011, many online consumers were presented with a deal that at face value might sound too good to be true. Recipients registering at the site could pay $10 and receive a $20 Amazon gift card. And if that alone wasn't motive enough, LivingSocial threw out a further incentive: If a buyer got three friends to purchase the deal as well, he or she would receive the gift card for free.

Many savvy consumers in fact would probably already be familiar with sites like LivingSocial and the deals it offers. As the second largest online deal-a-day Web site, LivingSocial is one of numerous similar start-up sites playing catch-up to market leader Groupon. The model for such Web sites is relatively straightforward, as they function roughly as marketing vehicles for local small businesses, generating publicity and facilitating transactions. The site, say Groupon, would initiate coupon offerings geographically (based on city) by working out deals with local retailers, restaurants, and other businesses. Discounts can be significant, ranging from 50 percent to as much as 90 percent off. Businesses would sell the coupons to consumers directly, and as the go-between, Groupon would take a cut, usually about 30 percent after the discount.

So how does a $20 Amazon gift card for $10 fit into the equation, especially since Amazon wouldn't exactly qualify as a "small local business"? As an added twist, LivingSocial and Amazon decided to forgo the typical sales arrangement; LivingSocial purchased the gift cards from Amazon and sold them directly. And although the terms of the exchange were not disclosed, if LivingSocial purchased them at face value, it would certainly absorb the losses itself. But if LivingSocial takes such a heavy loss on the deal, how would Amazon justify the $175 million investment it made in LivingSocial in December 2010, just before the gift card offer?

The answer lies within the 1.3 million coupons LivingSocial managed to sell through the promotion, which beat the $11 million in sales that rival Groupon generated when it offered a similar national deal with Gap. Prior to the deal, LivingSocial-valued at an estimated $1 billion-had 17 million members prior to offering the deal compared to the 50 million subscribers of Groupon, which had recently turned down a $6 billion offer from Google. Now compare the 1.3 million Amazon gift cards to the average number of coupons that Groupon sold per deal over the first quarter of 2010. At only 1,848, it becomes pretty clear that national deals like Groupon's Gap coupon and the Amazon gift cards are not about driving sales for Gap and Amazon, nor are they about profitability. They're about driving sales volume, increasing name exposure, and pulling in new members.

According to Caris Company analyst Sandeep Aggarwal, "These companies are in a land grabbing stage; the more members they sign up, the better deals they bring in. It clearly helps them generate higher revenue." So for a company like LivingSocial trying to play catch-up to market leader Groupon, a high-profile national deal like the Amazon offer makes sense. In December 2010, Groupon held a commanding lead over other group coupon sites in terms of its share of total U.S. site visits, leading second place LivingSocial by almost a full order of magnitude (0.033 percent to 0.0036 percent).

This land grab stage becomes increasingly important as there is clearly still room to grow. From Q4 of 2009 to Q1 of 2010, Groupon saw significant growth in nearly every major sales metric, from average buyers per deal (111 percent), to average deal price ($27.20 to $38.36), to average gross per sale (102 percent). Unique visitors rose from 900,000 in September 2009 to three million in March 2010. So while Groupon may have a huge head start, other companies can still find deals to attract significant attention. Barriers to entry remain low, with minimal existing technological advantages and little preventing local vendors or buyers form using multiple platforms. And as neither Groupon nor LivingSocial have reported seeing subscriber fatigue from receiving daily deal advertisements, the distribution model remains viable. How long this will last, however, is an entirely different question, making moves to grab subscribers (such as LivingSocial's Amazon deal) all the more important.

Which pricing objective was Living Social adopting with its Amazon gift card offer?

Many savvy consumers in fact would probably already be familiar with sites like LivingSocial and the deals it offers. As the second largest online deal-a-day Web site, LivingSocial is one of numerous similar start-up sites playing catch-up to market leader Groupon. The model for such Web sites is relatively straightforward, as they function roughly as marketing vehicles for local small businesses, generating publicity and facilitating transactions. The site, say Groupon, would initiate coupon offerings geographically (based on city) by working out deals with local retailers, restaurants, and other businesses. Discounts can be significant, ranging from 50 percent to as much as 90 percent off. Businesses would sell the coupons to consumers directly, and as the go-between, Groupon would take a cut, usually about 30 percent after the discount.

So how does a $20 Amazon gift card for $10 fit into the equation, especially since Amazon wouldn't exactly qualify as a "small local business"? As an added twist, LivingSocial and Amazon decided to forgo the typical sales arrangement; LivingSocial purchased the gift cards from Amazon and sold them directly. And although the terms of the exchange were not disclosed, if LivingSocial purchased them at face value, it would certainly absorb the losses itself. But if LivingSocial takes such a heavy loss on the deal, how would Amazon justify the $175 million investment it made in LivingSocial in December 2010, just before the gift card offer?

The answer lies within the 1.3 million coupons LivingSocial managed to sell through the promotion, which beat the $11 million in sales that rival Groupon generated when it offered a similar national deal with Gap. Prior to the deal, LivingSocial-valued at an estimated $1 billion-had 17 million members prior to offering the deal compared to the 50 million subscribers of Groupon, which had recently turned down a $6 billion offer from Google. Now compare the 1.3 million Amazon gift cards to the average number of coupons that Groupon sold per deal over the first quarter of 2010. At only 1,848, it becomes pretty clear that national deals like Groupon's Gap coupon and the Amazon gift cards are not about driving sales for Gap and Amazon, nor are they about profitability. They're about driving sales volume, increasing name exposure, and pulling in new members.

According to Caris Company analyst Sandeep Aggarwal, "These companies are in a land grabbing stage; the more members they sign up, the better deals they bring in. It clearly helps them generate higher revenue." So for a company like LivingSocial trying to play catch-up to market leader Groupon, a high-profile national deal like the Amazon offer makes sense. In December 2010, Groupon held a commanding lead over other group coupon sites in terms of its share of total U.S. site visits, leading second place LivingSocial by almost a full order of magnitude (0.033 percent to 0.0036 percent).

This land grab stage becomes increasingly important as there is clearly still room to grow. From Q4 of 2009 to Q1 of 2010, Groupon saw significant growth in nearly every major sales metric, from average buyers per deal (111 percent), to average deal price ($27.20 to $38.36), to average gross per sale (102 percent). Unique visitors rose from 900,000 in September 2009 to three million in March 2010. So while Groupon may have a huge head start, other companies can still find deals to attract significant attention. Barriers to entry remain low, with minimal existing technological advantages and little preventing local vendors or buyers form using multiple platforms. And as neither Groupon nor LivingSocial have reported seeing subscriber fatigue from receiving daily deal advertisements, the distribution model remains viable. How long this will last, however, is an entirely different question, making moves to grab subscribers (such as LivingSocial's Amazon deal) all the more important.

Which pricing objective was Living Social adopting with its Amazon gift card offer?

The pricing strategy employed by the living website through its sale of gift cards was market share pricing. Market share can be defined as a company's product sales as a percentage of the total sales within that specific industry. The website was trying to increase its sales volume, level of exposure, and draw in new site members. The sale of the gift cards was a means to increase its market share within online coupon industry against its major competitor.

4

Advanced Bio Medics (ABM) has invented a new stem-cell-based drug that will arrest even advanced forms of lung cancer. Development costs were actually quite low because the drug was an accidental discovery by scientists working on a different project. To stop the disease requires a regimen of one pill per week for 20 weeks. There is no substitute offered by competitors. ABM is thinking that it could maximize its profits by charging $10,000 per pill. Of course, many people will die because they can't afford the medicine at this price.

Questions

Should ABM maximize its profits?

Questions

Should ABM maximize its profits?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 10 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

In the last part of your strategic marketing plan you began the process of defining the marketing mix, starting with the components of product, distribution, and promotion. The next stage of the strategic planning process-pricing-completes the elements of the marketing mix. In recent years, pricing has become a special challenge to the marketer because prices can be quickly and easily compared on the Internet.

In any case, your goal should be to make pricing competitive and value-driven, as well as cover costs. Other features and benefits of your offering are likely to be more important than price. Use the following exercises to guide you through the pricing part of your strategic marketing plan:

1. List possible pricing objectives for your chosen firm. How might adopting different pricing objectives change the behavior of the firm and its marketing plans?

2. Gather information on tactics you decided on for the first parts of your marketing plan. What costs are associated with those decisions? Will you incur more or fewer costs by selling online? Will your marketing costs increase or decrease? Why? Calculate the break-even point for selling your offering. Can you sell enough to cover your costs? Try the break-even calculator at http://connection.cwru.edu/mbac424/breakeven/BreakEven.html.

3. Pricing is an integral component of marketing strategy. Discuss how your firm's pricing can affect or be affected by competition, the economic environment, political regulations, product features, extra customer service, changes in distribution, or changes in promotion.

4. Is demand elastic or inelastic for your company's product or service? Why? What is the demand elasticity for your offering in an off-line world? Whatever the level, it is likely to be more elastic online. What tactics can you use to soften or reduce this online price sensitivity?

In any case, your goal should be to make pricing competitive and value-driven, as well as cover costs. Other features and benefits of your offering are likely to be more important than price. Use the following exercises to guide you through the pricing part of your strategic marketing plan:

1. List possible pricing objectives for your chosen firm. How might adopting different pricing objectives change the behavior of the firm and its marketing plans?

2. Gather information on tactics you decided on for the first parts of your marketing plan. What costs are associated with those decisions? Will you incur more or fewer costs by selling online? Will your marketing costs increase or decrease? Why? Calculate the break-even point for selling your offering. Can you sell enough to cover your costs? Try the break-even calculator at http://connection.cwru.edu/mbac424/breakeven/BreakEven.html.

3. Pricing is an integral component of marketing strategy. Discuss how your firm's pricing can affect or be affected by competition, the economic environment, political regulations, product features, extra customer service, changes in distribution, or changes in promotion.

4. Is demand elastic or inelastic for your company's product or service? Why? What is the demand elasticity for your offering in an off-line world? Whatever the level, it is likely to be more elastic online. What tactics can you use to soften or reduce this online price sensitivity?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 10 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

As long as people have stomach aches, companies will sell remedies. Acid+All is banking that America will continue its love affair with bad food and has made an interesting move into the antacid market. The tiny pills come packaged in a tin priced at $3.89, which clearly sets the product apart from competitors like Rolaids, Tums, and others. The gambit of staking out a position as a prestige product is high. Watch the video to see what issues helped forge the $3.89 unit price and if the company has been successful at this price point.

Would you expect demand for Acid+All to be elastic? Why or why not?

Would you expect demand for Acid+All to be elastic? Why or why not?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 10 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

On January 20, 2011, many online consumers were presented with a deal that at face value might sound too good to be true. Recipients registering at the site could pay $10 and receive a $20 Amazon gift card. And if that alone wasn't motive enough, LivingSocial threw out a further incentive: If a buyer got three friends to purchase the deal as well, he or she would receive the gift card for free.

Many savvy consumers in fact would probably already be familiar with sites like LivingSocial and the deals it offers. As the second largest online deal-a-day Web site, LivingSocial is one of numerous similar start-up sites playing catch-up to market leader Groupon. The model for such Web sites is relatively straightforward, as they function roughly as marketing vehicles for local small businesses, generating publicity and facilitating transactions. The site, say Groupon, would initiate coupon offerings geographically (based on city) by working out deals with local retailers, restaurants, and other businesses. Discounts can be significant, ranging from 50 percent to as much as 90 percent off. Businesses would sell the coupons to consumers directly, and as the go-between, Groupon would take a cut, usually about 30 percent after the discount.

So how does a $20 Amazon gift card for $10 fit into the equation, especially since Amazon wouldn't exactly qualify as a "small local business"? As an added twist, LivingSocial and Amazon decided to forgo the typical sales arrangement; LivingSocial purchased the gift cards from Amazon and sold them directly. And although the terms of the exchange were not disclosed, if LivingSocial purchased them at face value, it would certainly absorb the losses itself. But if LivingSocial takes such a heavy loss on the deal, how would Amazon justify the $175 million investment it made in LivingSocial in December 2010, just before the gift card offer?

The answer lies within the 1.3 million coupons LivingSocial managed to sell through the promotion, which beat the $11 million in sales that rival Groupon generated when it offered a similar national deal with Gap. Prior to the deal, LivingSocial-valued at an estimated $1 billion-had 17 million members prior to offering the deal compared to the 50 million subscribers of Groupon, which had recently turned down a $6 billion offer from Google. Now compare the 1.3 million Amazon gift cards to the average number of coupons that Groupon sold per deal over the first quarter of 2010. At only 1,848, it becomes pretty clear that national deals like Groupon's Gap coupon and the Amazon gift cards are not about driving sales for Gap and Amazon, nor are they about profitability. They're about driving sales volume, increasing name exposure, and pulling in new members.

According to Caris Company analyst Sandeep Aggarwal, "These companies are in a land grabbing stage; the more members they sign up, the better deals they bring in. It clearly helps them generate higher revenue." So for a company like LivingSocial trying to play catch-up to market leader Groupon, a high-profile national deal like the Amazon offer makes sense. In December 2010, Groupon held a commanding lead over other group coupon sites in terms of its share of total U.S. site visits, leading second place LivingSocial by almost a full order of magnitude (0.033 percent to 0.0036 percent).

This land grab stage becomes increasingly important as there is clearly still room to grow. From Q4 of 2009 to Q1 of 2010, Groupon saw significant growth in nearly every major sales metric, from average buyers per deal (111 percent), to average deal price ($27.20 to $38.36), to average gross per sale (102 percent). Unique visitors rose from 900,000 in September 2009 to three million in March 2010. So while Groupon may have a huge head start, other companies can still find deals to attract significant attention. Barriers to entry remain low, with minimal existing technological advantages and little preventing local vendors or buyers form using multiple platforms. And as neither Groupon nor LivingSocial have reported seeing subscriber fatigue from receiving daily deal advertisements, the distribution model remains viable. How long this will last, however, is an entirely different question, making moves to grab subscribers (such as LivingSocial's Amazon deal) all the more important.

For a small business using a Group on or Living Social, the deal itself typically would not be very profitable. Most likely the motivation for small businesses would also be to draw new customers and increase exposure. Some people question how effective these deals can be though for small businesses beyond the short-term bump in traffic. Do you think these deals can benefit small businesses in the long run? If you ran a small business, would you offer deals through Group on or Living Social? Why or why not?

Many savvy consumers in fact would probably already be familiar with sites like LivingSocial and the deals it offers. As the second largest online deal-a-day Web site, LivingSocial is one of numerous similar start-up sites playing catch-up to market leader Groupon. The model for such Web sites is relatively straightforward, as they function roughly as marketing vehicles for local small businesses, generating publicity and facilitating transactions. The site, say Groupon, would initiate coupon offerings geographically (based on city) by working out deals with local retailers, restaurants, and other businesses. Discounts can be significant, ranging from 50 percent to as much as 90 percent off. Businesses would sell the coupons to consumers directly, and as the go-between, Groupon would take a cut, usually about 30 percent after the discount.

So how does a $20 Amazon gift card for $10 fit into the equation, especially since Amazon wouldn't exactly qualify as a "small local business"? As an added twist, LivingSocial and Amazon decided to forgo the typical sales arrangement; LivingSocial purchased the gift cards from Amazon and sold them directly. And although the terms of the exchange were not disclosed, if LivingSocial purchased them at face value, it would certainly absorb the losses itself. But if LivingSocial takes such a heavy loss on the deal, how would Amazon justify the $175 million investment it made in LivingSocial in December 2010, just before the gift card offer?

The answer lies within the 1.3 million coupons LivingSocial managed to sell through the promotion, which beat the $11 million in sales that rival Groupon generated when it offered a similar national deal with Gap. Prior to the deal, LivingSocial-valued at an estimated $1 billion-had 17 million members prior to offering the deal compared to the 50 million subscribers of Groupon, which had recently turned down a $6 billion offer from Google. Now compare the 1.3 million Amazon gift cards to the average number of coupons that Groupon sold per deal over the first quarter of 2010. At only 1,848, it becomes pretty clear that national deals like Groupon's Gap coupon and the Amazon gift cards are not about driving sales for Gap and Amazon, nor are they about profitability. They're about driving sales volume, increasing name exposure, and pulling in new members.

According to Caris Company analyst Sandeep Aggarwal, "These companies are in a land grabbing stage; the more members they sign up, the better deals they bring in. It clearly helps them generate higher revenue." So for a company like LivingSocial trying to play catch-up to market leader Groupon, a high-profile national deal like the Amazon offer makes sense. In December 2010, Groupon held a commanding lead over other group coupon sites in terms of its share of total U.S. site visits, leading second place LivingSocial by almost a full order of magnitude (0.033 percent to 0.0036 percent).

This land grab stage becomes increasingly important as there is clearly still room to grow. From Q4 of 2009 to Q1 of 2010, Groupon saw significant growth in nearly every major sales metric, from average buyers per deal (111 percent), to average deal price ($27.20 to $38.36), to average gross per sale (102 percent). Unique visitors rose from 900,000 in September 2009 to three million in March 2010. So while Groupon may have a huge head start, other companies can still find deals to attract significant attention. Barriers to entry remain low, with minimal existing technological advantages and little preventing local vendors or buyers form using multiple platforms. And as neither Groupon nor LivingSocial have reported seeing subscriber fatigue from receiving daily deal advertisements, the distribution model remains viable. How long this will last, however, is an entirely different question, making moves to grab subscribers (such as LivingSocial's Amazon deal) all the more important.

For a small business using a Group on or Living Social, the deal itself typically would not be very profitable. Most likely the motivation for small businesses would also be to draw new customers and increase exposure. Some people question how effective these deals can be though for small businesses beyond the short-term bump in traffic. Do you think these deals can benefit small businesses in the long run? If you ran a small business, would you offer deals through Group on or Living Social? Why or why not?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 10 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

Advanced Bio Medics (ABM) has invented a new stem-cell-based drug that will arrest even advanced forms of lung cancer. Development costs were actually quite low because the drug was an accidental discovery by scientists working on a different project. To stop the disease requires a regimen of one pill per week for 20 weeks. There is no substitute offered by competitors. ABM is thinking that it could maximize its profits by charging $10,000 per pill. Of course, many people will die because they can't afford the medicine at this price.

Questions

Does the AMA Statement of Ethics address this issue? Go to www.marketing power.com and review the code. Then, write a brief paragraph on what the AMA Statement of Ethics contains that relates to ABM's dilemma.

Questions

Does the AMA Statement of Ethics address this issue? Go to www.marketing power.com and review the code. Then, write a brief paragraph on what the AMA Statement of Ethics contains that relates to ABM's dilemma.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 10 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

As long as people have stomach aches, companies will sell remedies. Acid+All is banking that America will continue its love affair with bad food and has made an interesting move into the antacid market. The tiny pills come packaged in a tin priced at $3.89, which clearly sets the product apart from competitors like Rolaids, Tums, and others. The gambit of staking out a position as a prestige product is high. Watch the video to see what issues helped forge the $3.89 unit price and if the company has been successful at this price point.

What role do the product life cycle, competition, and perceptions of quality play in Acid+All's suggested retail price?

What role do the product life cycle, competition, and perceptions of quality play in Acid+All's suggested retail price?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 10 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

As long as people have stomach aches, companies will sell remedies. Acid+All is banking that America will continue its love affair with bad food and has made an interesting move into the antacid market. The tiny pills come packaged in a tin priced at $3.89, which clearly sets the product apart from competitors like Rolaids, Tums, and others. The gambit of staking out a position as a prestige product is high. Watch the video to see what issues helped forge the $3.89 unit price and if the company has been successful at this price point.

Would you buy Acid+All for the $3.89 retail price? Why or why not?

Would you buy Acid+All for the $3.89 retail price? Why or why not?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 10 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck