Deck 10: Managing Organizational Structure and Culture

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Question

Unlock Deck

Sign up to unlock the cards in this deck!

Unlock Deck

Unlock Deck

1/30

Play

Full screen (f)

Deck 10: Managing Organizational Structure and Culture

1

Can you think of any ways in which a typical job could be enlarged or enriched?

The job enrichment and enlargement are possible only when an employee finds his/ her job motivating and encouraging and it carries some meaningfulness. The job characteristics model is a framework for job design which enables a manger look into the factors which make a job more interesting and motivating. This model shows the opportunities to improve the motivation and encouragement of the employees in their jobs.

The company concerned is a major automobile manufacturer of Japan in this context. The company is well-established in Japan as well as in global automobile market at least from last 30 years. The company is famous for developing small and medium sized affordable cars in the market in a small lead time of introduction. The success of the company is leveraged primarily on the efficiency improvement, lean operations, cost reduction, and economies of scale. The company is not too innovative is adopting new technology or developing new models equipped with such technologies. The target market has been primarily the middle-class customers who are not willing to pay too high for owning a car

The company lacks the skill variety and task identity part of job characteristics which can be improved using some or all of the following methods.

• The managers should devise a policy for job rotation and multi-skilling in the lower level. At the higher level of the hierarchy a planned growth within and between functions should be implemented at least for the performing employees.

• Within a function, the mangers and supervisors should be given ample authority of their respective areas and processes so as to improve the task identity.

The company concerned is a major automobile manufacturer of Japan in this context. The company is well-established in Japan as well as in global automobile market at least from last 30 years. The company is famous for developing small and medium sized affordable cars in the market in a small lead time of introduction. The success of the company is leveraged primarily on the efficiency improvement, lean operations, cost reduction, and economies of scale. The company is not too innovative is adopting new technology or developing new models equipped with such technologies. The target market has been primarily the middle-class customers who are not willing to pay too high for owning a car

The company lacks the skill variety and task identity part of job characteristics which can be improved using some or all of the following methods.

• The managers should devise a policy for job rotation and multi-skilling in the lower level. At the higher level of the hierarchy a planned growth within and between functions should be implemented at least for the performing employees.

• Within a function, the mangers and supervisors should be given ample authority of their respective areas and processes so as to improve the task identity.

2

Larry Page's Google 3.0: The company co-founder and his star deputies are trying to root out bureaucracy and rediscover the nimble moves of youth.

Every Monday afternoon at the Googleplex in Mountain View, Calif., more than a dozen of Google's top executives gather in the company's boardroom. The weekly meeting, known as Execute, was launched last summer with a specific mission: to get the near-sovereign leaders of Google's far-flung product groups into a single room and harmonize their disparate initiatives. Google cofounder Sergey Brin runs the meeting, along with new Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and soonto-be-former CEO Eric Schmidt. The unstated goal is to save the search giant from the ossification that can paralyze large corporations.

It won't be easy, because Google is a tech conglomerate, an assemblage of parts that sometimes work at cross-purposes. Among the most important barons at the meeting: Andy Rubin, who oversees the Android operating system for mobile phones; Salar Kamangar, who runs the videosharing site YouTube; and Vic Gundotra, who heads up Google's secret project to combat the social network Facebook. "We needed to get these different product leaders together to find time to talk through all the integration points," says Page during a telephone interview with Bloomberg BusinessWeek minutes before a late-January Execute session. "Every time we increase the size of the company, we need to keep things going to make sure we keep our speed, pace, and passion."

The new weekly ritual-like the surprise announcement on Jan. 20 that Page will take over from Schmidt in April-marks a significant shift in strategy at the world's most famous Internet company. Welcome to Google 3.0. In the 1.0 era, which ran from 1996 to 2001, Page and Brin incubated the company at Stanford University and in a Menlo Park (Calif.) garage. In 2001 they ushered in the triumphant 2.0 era by hiring Schmidt, a tech industry grown-up who'd been CEO of Novell. Now comes the third phase, led by Page and dedicated to rooting out bureaucracy and rediscovering the nimble moves of youth.

Although Google recently reported that fourth-quarter profits jumped 29% over the previous year, its stock rose only 13.7% over the past 12 months and perhaps the most serious rap against the company: that its loosely organized structure is growing unwieldy and counterproductive. The creative chaos inside Google's halls-a decentralized jungle of innovation, as one prominent venture capitalist puts it-once empowered employees to make bold moves, such as creating Gmail, the search-based e-mail system. Other than Android, the culture has recently produced a string of flops, such as Google Buzz, a Twitter clone, and Google Wave, a wonky service that let people collaborate online. Page doesn't explicitly blame those missteps on the company's loosely knit management or the famous troika at the top. Yet he concedes, "We do pay a price for [shared decision making], in terms of speed and people not necessarily knowing where they go to ask questions." His elevation to CEO, he says, "is really a clarification of our roles. I think it will help with our speed."

Former Google employees are encouraged. "Larry is a visionary, the kind of person that inspires people to do more, be better, reach farther," says Douglas Merrill, Google's chief information officer until 2008. "He would walk around the engineering department and, with just a word or two, guide or redirect projects and leave the developers feeling great about the coaching." Page says one of his goals is to take the decisive leadership style they have shown within their product groups, spread it across the company, and apply it to major decisions. "We've been inspired by a lot of the people who have been operating with more autonomy and clear decision-making authority," he says.

For example, Andy Rubin is as adept at creating mechanical marvels in his home as he is writing the software that runs tablets and mobile phones. His latest invention, produced with several Google colleagues, is "Java the Bot," a wheeled two-armed robot that can roll up to an espresso machine and perform all the steps needed to make a decent cup of coffee. (It's still in development.) Since Google acquired his eight-person start-up, Android, in 2005, Rubin has expended most of his entrepreneurial energy within the Googleplex. His Android platform has pulled off arguably the fastest land grab in tech history, jumping from also-ran to market leader with 26% of the smartphone market, vs. 25% for iPhone (BlackBerry was first, with 33%, but is losing ground). Android's success has made Rubin a model inside Google for how executives can run units autonomously. "We need even more of those," Page says of Android.

Because Rubin's mission to create a mobile operating system was so distinct from the rest of Google's goals, he was given unique leeway in managing his division. He can hire his own team and even controls the landscaping around his office building, which he decorates with supersized ornaments of the desserts (éclair, cupcake) that give versions of Android their name. Google "did a very good job of giving us autonomy," Rubin says. "We can move really, really quickly." Page, Brin, and Schmidt deserve much of the credit for Google's success-but not all of it. "The key to making Google viable was the people they hired in the early days, many of whom are still there and are super-rich," says Steven Levy, author of the forthcoming book In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives. "They are part of the inner circle that makes the big decisions."

Over the past few years, Google has lost a stream of executives to startups, venture capital firms, and, most embarrassingly, Facebook. Sundar Pichai bucked the trend. A vice president for product management in charge of the Chrome browser, Pichai, 38, was recently courted by Twitter, the hot microblogging startup. Pichai won't say whether Google sweetened his compensation, but he confirms that he's not leaving. "I'm staying. I'm happy here," he says. "I look at this as a life journey that I've been on for a long time."

How social media will and won't change Google's world is an ongoing conversation at Google's weekly Execute meetings-and it underscores Larry Page's biggest problem as Google's new CEO. Page values strong, idiosyncratic leaders who know their domains and have their own aggressive agendas. All these rising stars have to work together. The mobile team has to coordinate with the nascent local and e-commerce groups. Rubin's app-based Android vision of the future has to square with Pichai's push for the wide-open Web of Chrome OS; and Singhal's search division has to find common ground with Vic Gundotra and the new czars of social. Can they integrate their plans while satisfying Larry Page's need for speed? At some point, Page may have to dispense with the philosophical discussions, put some limits on the open atmosphere of geeky experimentation, and make some tough decisions. It's not very "Googley." But it's the central challenge of Google 3.0.

How would you describe how Google's organizational structure has developed since its founding?

Every Monday afternoon at the Googleplex in Mountain View, Calif., more than a dozen of Google's top executives gather in the company's boardroom. The weekly meeting, known as Execute, was launched last summer with a specific mission: to get the near-sovereign leaders of Google's far-flung product groups into a single room and harmonize their disparate initiatives. Google cofounder Sergey Brin runs the meeting, along with new Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and soonto-be-former CEO Eric Schmidt. The unstated goal is to save the search giant from the ossification that can paralyze large corporations.

It won't be easy, because Google is a tech conglomerate, an assemblage of parts that sometimes work at cross-purposes. Among the most important barons at the meeting: Andy Rubin, who oversees the Android operating system for mobile phones; Salar Kamangar, who runs the videosharing site YouTube; and Vic Gundotra, who heads up Google's secret project to combat the social network Facebook. "We needed to get these different product leaders together to find time to talk through all the integration points," says Page during a telephone interview with Bloomberg BusinessWeek minutes before a late-January Execute session. "Every time we increase the size of the company, we need to keep things going to make sure we keep our speed, pace, and passion."

The new weekly ritual-like the surprise announcement on Jan. 20 that Page will take over from Schmidt in April-marks a significant shift in strategy at the world's most famous Internet company. Welcome to Google 3.0. In the 1.0 era, which ran from 1996 to 2001, Page and Brin incubated the company at Stanford University and in a Menlo Park (Calif.) garage. In 2001 they ushered in the triumphant 2.0 era by hiring Schmidt, a tech industry grown-up who'd been CEO of Novell. Now comes the third phase, led by Page and dedicated to rooting out bureaucracy and rediscovering the nimble moves of youth.

Although Google recently reported that fourth-quarter profits jumped 29% over the previous year, its stock rose only 13.7% over the past 12 months and perhaps the most serious rap against the company: that its loosely organized structure is growing unwieldy and counterproductive. The creative chaos inside Google's halls-a decentralized jungle of innovation, as one prominent venture capitalist puts it-once empowered employees to make bold moves, such as creating Gmail, the search-based e-mail system. Other than Android, the culture has recently produced a string of flops, such as Google Buzz, a Twitter clone, and Google Wave, a wonky service that let people collaborate online. Page doesn't explicitly blame those missteps on the company's loosely knit management or the famous troika at the top. Yet he concedes, "We do pay a price for [shared decision making], in terms of speed and people not necessarily knowing where they go to ask questions." His elevation to CEO, he says, "is really a clarification of our roles. I think it will help with our speed."

Former Google employees are encouraged. "Larry is a visionary, the kind of person that inspires people to do more, be better, reach farther," says Douglas Merrill, Google's chief information officer until 2008. "He would walk around the engineering department and, with just a word or two, guide or redirect projects and leave the developers feeling great about the coaching." Page says one of his goals is to take the decisive leadership style they have shown within their product groups, spread it across the company, and apply it to major decisions. "We've been inspired by a lot of the people who have been operating with more autonomy and clear decision-making authority," he says.

For example, Andy Rubin is as adept at creating mechanical marvels in his home as he is writing the software that runs tablets and mobile phones. His latest invention, produced with several Google colleagues, is "Java the Bot," a wheeled two-armed robot that can roll up to an espresso machine and perform all the steps needed to make a decent cup of coffee. (It's still in development.) Since Google acquired his eight-person start-up, Android, in 2005, Rubin has expended most of his entrepreneurial energy within the Googleplex. His Android platform has pulled off arguably the fastest land grab in tech history, jumping from also-ran to market leader with 26% of the smartphone market, vs. 25% for iPhone (BlackBerry was first, with 33%, but is losing ground). Android's success has made Rubin a model inside Google for how executives can run units autonomously. "We need even more of those," Page says of Android.

Because Rubin's mission to create a mobile operating system was so distinct from the rest of Google's goals, he was given unique leeway in managing his division. He can hire his own team and even controls the landscaping around his office building, which he decorates with supersized ornaments of the desserts (éclair, cupcake) that give versions of Android their name. Google "did a very good job of giving us autonomy," Rubin says. "We can move really, really quickly." Page, Brin, and Schmidt deserve much of the credit for Google's success-but not all of it. "The key to making Google viable was the people they hired in the early days, many of whom are still there and are super-rich," says Steven Levy, author of the forthcoming book In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives. "They are part of the inner circle that makes the big decisions."

Over the past few years, Google has lost a stream of executives to startups, venture capital firms, and, most embarrassingly, Facebook. Sundar Pichai bucked the trend. A vice president for product management in charge of the Chrome browser, Pichai, 38, was recently courted by Twitter, the hot microblogging startup. Pichai won't say whether Google sweetened his compensation, but he confirms that he's not leaving. "I'm staying. I'm happy here," he says. "I look at this as a life journey that I've been on for a long time."

How social media will and won't change Google's world is an ongoing conversation at Google's weekly Execute meetings-and it underscores Larry Page's biggest problem as Google's new CEO. Page values strong, idiosyncratic leaders who know their domains and have their own aggressive agendas. All these rising stars have to work together. The mobile team has to coordinate with the nascent local and e-commerce groups. Rubin's app-based Android vision of the future has to square with Pichai's push for the wide-open Web of Chrome OS; and Singhal's search division has to find common ground with Vic Gundotra and the new czars of social. Can they integrate their plans while satisfying Larry Page's need for speed? At some point, Page may have to dispense with the philosophical discussions, put some limits on the open atmosphere of geeky experimentation, and make some tough decisions. It's not very "Googley." But it's the central challenge of Google 3.0.

How would you describe how Google's organizational structure has developed since its founding?

Company G is well known for promoting innovation in a decentralized way. Over a period of time, it has encouraged creativity and developed a strong entrepreneurial culture. It encouraged its employees to be innovative, own up the ideas that they come up with and accept blame if they fail.

As a result, the company structure is not very well defined. Product groups within the company are working more or less like independent companies.

Loosely defined structure yielded favorable results in past by making significant breakthrough in technology. But the recent performance on this count is not encouraging. A series of recent products have flopped in the market.

Many believe that organization structure is to be blamed. Financial market seems to be penalizing the company for its loose organization structure because its share price has not grown as fast as its profit. Its new CEO is working towards addressing the issue.

He has taken steps to bring various product groups together to ensure that there is coordination among various initiatives and integration at the organizational level. CEO would have to find ways to increase the speed with which its innovation is reaching the market. He may have to put some structure in place to ensure that there is some level of filtration for innovative ideas before ideas get approved.

Over the year, company G has valued creative innovation. It has encouraged its employees to be more like entrepreneurs. For innovation to take roots, it is necessary that ideas get funded and resources get allocated to explore the ideas in detail.

This required that ideas do not get held up in lengthy approval processes. Funding and resources are released immediately without having the senior management to review the ideas. This has resulted in decentralized organizational structure.

Decentralized authority refers to the fact that decision making authority is decentralized with middle level managers. Decentralized decision making reduces the duplication of work by reducing the number of people who need to approve of a decision in centralized authority. This also free up senior management to perform other important tasks.

Company G organized itself along product lines. This gave rise to product departmentalization. Product departmentalization is characterized by departments being formed along product lines or services line.

The present structure of company G is best described as product based departmentalization with highly decentralized authority.

As a result, the company structure is not very well defined. Product groups within the company are working more or less like independent companies.

Loosely defined structure yielded favorable results in past by making significant breakthrough in technology. But the recent performance on this count is not encouraging. A series of recent products have flopped in the market.

Many believe that organization structure is to be blamed. Financial market seems to be penalizing the company for its loose organization structure because its share price has not grown as fast as its profit. Its new CEO is working towards addressing the issue.

He has taken steps to bring various product groups together to ensure that there is coordination among various initiatives and integration at the organizational level. CEO would have to find ways to increase the speed with which its innovation is reaching the market. He may have to put some structure in place to ensure that there is some level of filtration for innovative ideas before ideas get approved.

Over the year, company G has valued creative innovation. It has encouraged its employees to be more like entrepreneurs. For innovation to take roots, it is necessary that ideas get funded and resources get allocated to explore the ideas in detail.

This required that ideas do not get held up in lengthy approval processes. Funding and resources are released immediately without having the senior management to review the ideas. This has resulted in decentralized organizational structure.

Decentralized authority refers to the fact that decision making authority is decentralized with middle level managers. Decentralized decision making reduces the duplication of work by reducing the number of people who need to approve of a decision in centralized authority. This also free up senior management to perform other important tasks.

Company G organized itself along product lines. This gave rise to product departmentalization. Product departmentalization is characterized by departments being formed along product lines or services line.

The present structure of company G is best described as product based departmentalization with highly decentralized authority.

3

Go to the website of Kraft, the food services company ( www.kraft.com ). Click on "Corporate Information" and then explore its brands.

Why did Kraft decide to split up into two different companies in 2011?

Why did Kraft decide to split up into two different companies in 2011?

Not Answer

4

Discuss ways in which you can improve the way the current functional structure operates to speed website development.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

5

How might a salesperson's job or a secretary's job be enlarged or enriched to make it more motivating?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

6

Which contingencies are most important in explaining how the organization is organized? Do you think it is organized in the right way?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

7

Speeding Up Website Design

You have been hired by a website design, production, and hosting company whose new animated website designs are attracting a lot of attention and many customers. Currently, employees are organized into different functions such as hardware, software design, graphic art, and website hosting, as well as functions such as marketing and human resources. Each function takes its turn to work on a new project from initial customer request to final online website hosting.

The problem the company is experiencing is that it typically takes one year from the initial idea stage to the time a website is up and running; the company wants to shorten this time by half to protect and expand its market niche. In talking to other managers, you discover that they believe the company's current functional structure is the source of the problem-it is not allowing employees to develop websites fast enough to satisfy customers' demands. They want you to design a better structure.

What kind of culture would you help create to make the company's structure work more effectively?

You have been hired by a website design, production, and hosting company whose new animated website designs are attracting a lot of attention and many customers. Currently, employees are organized into different functions such as hardware, software design, graphic art, and website hosting, as well as functions such as marketing and human resources. Each function takes its turn to work on a new project from initial customer request to final online website hosting.

The problem the company is experiencing is that it typically takes one year from the initial idea stage to the time a website is up and running; the company wants to shorten this time by half to protect and expand its market niche. In talking to other managers, you discover that they believe the company's current functional structure is the source of the problem-it is not allowing employees to develop websites fast enough to satisfy customers' demands. They want you to design a better structure.

What kind of culture would you help create to make the company's structure work more effectively?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

8

Go to the website of Kraft, the food services company ( www.kraft.com ). Click on "Corporate Information" and then explore its brands.

Given the way it describes its brands, what kind of divisional structure do you think Kraft uses? Why do you think it uses this structure?

Given the way it describes its brands, what kind of divisional structure do you think Kraft uses? Why do you think it uses this structure?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

9

What kind of organization structure does the organization use? If it is part of a chain, what kind of structure does the entire organization use? What other structures might allow the organization to operate more effectively? For example, would the move to a product team structure lead to greater efficiency or effectiveness? Why or why not?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

10

Would a flexible or a more formal structure be most appropriate for each of these organizations: (a) a large department store (b) a Big Five accountancy firm (c) a biotechnology company? Explain your reasoning.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

11

When and under what conditions might managers change from a functional to (a) product (b) geographic, or (c) market structure?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

12

What ethical rules (see Chapter 3) should managers use to decide which employees to terminate when redesigning their hierarchy?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

13

How many levels are there in the organization's hierarchy? Is authority centralized or decentralized? Describe the span of control of the top manager and of middle or first-line managers.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

14

Bob's Appliances

Form groups of three or four people, and appoint one member as the spokesperson who will communicate your findings to the class when called on by the instructor. Then discuss the following scenario:

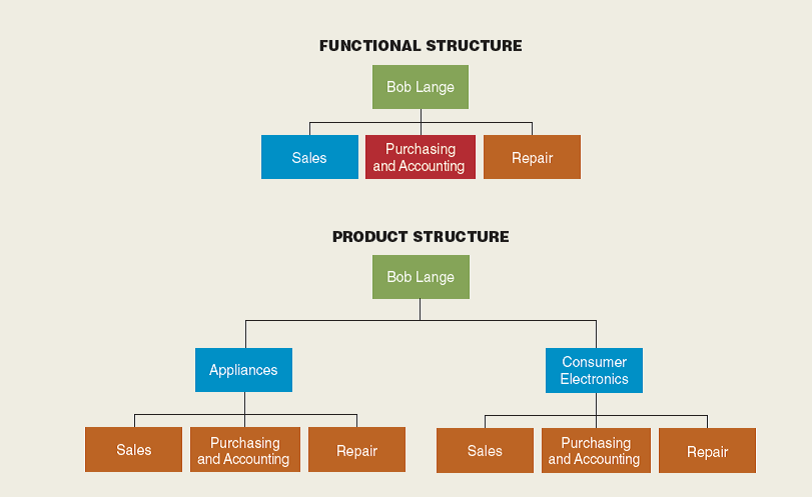

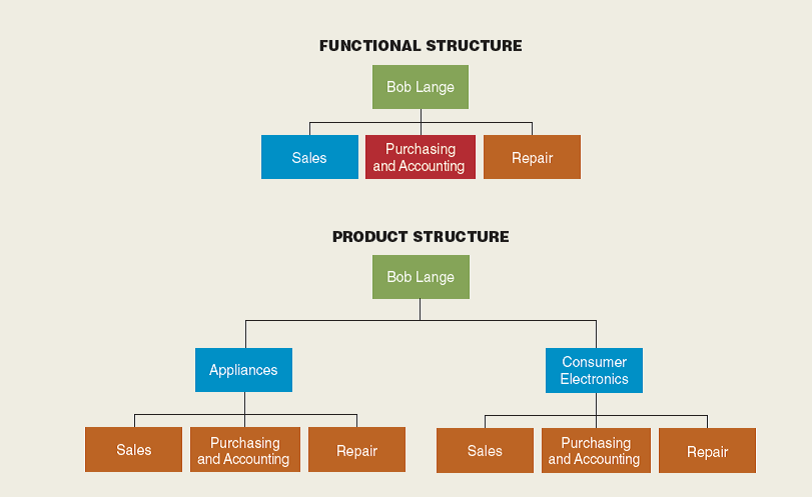

Bob's Appliances sells and services household appliances such as washing machines, dishwashers, ranges, and refrigerators. Over the years, the company has developed a good reputation for the quality of its customer service, and many local builders patronize the store. However, large retailers such as Best Buy, Walmart, and Costco are also providing an increasing range of appliances. Moreover, to attract more customers these stores also carry a complete range of consumer electronics products-LCD TVs, computers, and digital devices. Bob Lange, the owner of Bob's Appliances, has decided that if he is to stay in business, he must widen his product range and compete directly with the chains. In 2007 he decided to build a 20,000-square-foot store and service center, and he is now hiring new employees to sell and service the new line of consumer electronics. Because of his company's increased size, Lange is not sure of the best way to organize the employees. Currently he uses a functional structure; employees are ivided into sales, purchasing and accounting, and repair. Bob is wondering whether selling and servicing consumer electronics is so different from selling and servicing appliances that he should move to a product structure (see the accompanying figure) and create separate sets of functions for each of his two lines of business. 64

You are a team of local consultants whom Bob has called in to advise him as he makes this crucial choice. Which structure do you recommend? Why?

Form groups of three or four people, and appoint one member as the spokesperson who will communicate your findings to the class when called on by the instructor. Then discuss the following scenario:

Bob's Appliances sells and services household appliances such as washing machines, dishwashers, ranges, and refrigerators. Over the years, the company has developed a good reputation for the quality of its customer service, and many local builders patronize the store. However, large retailers such as Best Buy, Walmart, and Costco are also providing an increasing range of appliances. Moreover, to attract more customers these stores also carry a complete range of consumer electronics products-LCD TVs, computers, and digital devices. Bob Lange, the owner of Bob's Appliances, has decided that if he is to stay in business, he must widen his product range and compete directly with the chains. In 2007 he decided to build a 20,000-square-foot store and service center, and he is now hiring new employees to sell and service the new line of consumer electronics. Because of his company's increased size, Lange is not sure of the best way to organize the employees. Currently he uses a functional structure; employees are ivided into sales, purchasing and accounting, and repair. Bob is wondering whether selling and servicing consumer electronics is so different from selling and servicing appliances that he should move to a product structure (see the accompanying figure) and create separate sets of functions for each of his two lines of business. 64

You are a team of local consultants whom Bob has called in to advise him as he makes this crucial choice. Which structure do you recommend? Why?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

15

How do matrix structure and product team structure differ? Why is product team structure more widely used?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

16

Larry Page's Google 3.0: The company co-founder and his star deputies are trying to root out bureaucracy and rediscover the nimble moves of youth.

Every Monday afternoon at the Googleplex in Mountain View, Calif., more than a dozen of Google's top executives gather in the company's boardroom. The weekly meeting, known as Execute, was launched last summer with a specific mission: to get the near-sovereign leaders of Google's far-flung product groups into a single room and harmonize their disparate initiatives. Google cofounder Sergey Brin runs the meeting, along with new Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and soonto-be-former CEO Eric Schmidt. The unstated goal is to save the search giant from the ossification that can paralyze large corporations.

It won't be easy, because Google is a tech conglomerate, an assemblage of parts that sometimes work at cross-purposes. Among the most important barons at the meeting: Andy Rubin, who oversees the Android operating system for mobile phones; Salar Kamangar, who runs the videosharing site YouTube; and Vic Gundotra, who heads up Google's secret project to combat the social network Facebook. "We needed to get these different product leaders together to find time to talk through all the integration points," says Page during a telephone interview with Bloomberg BusinessWeek minutes before a late-January Execute session. "Every time we increase the size of the company, we need to keep things going to make sure we keep our speed, pace, and passion."

The new weekly ritual-like the surprise announcement on Jan. 20 that Page will take over from Schmidt in April-marks a significant shift in strategy at the world's most famous Internet company. Welcome to Google 3.0. In the 1.0 era, which ran from 1996 to 2001, Page and Brin incubated the company at Stanford University and in a Menlo Park (Calif.) garage. In 2001 they ushered in the triumphant 2.0 era by hiring Schmidt, a tech industry grown-up who'd been CEO of Novell. Now comes the third phase, led by Page and dedicated to rooting out bureaucracy and rediscovering the nimble moves of youth.

Although Google recently reported that fourth-quarter profits jumped 29% over the previous year, its stock rose only 13.7% over the past 12 months and perhaps the most serious rap against the company: that its loosely organized structure is growing unwieldy and counterproductive. The creative chaos inside Google's halls-a decentralized jungle of innovation, as one prominent venture capitalist puts it-once empowered employees to make bold moves, such as creating Gmail, the search-based e-mail system. Other than Android, the culture has recently produced a string of flops, such as Google Buzz, a Twitter clone, and Google Wave, a wonky service that let people collaborate online. Page doesn't explicitly blame those missteps on the company's loosely knit management or the famous troika at the top. Yet he concedes, "We do pay a price for [shared decision making], in terms of speed and people not necessarily knowing where they go to ask questions." His elevation to CEO, he says, "is really a clarification of our roles. I think it will help with our speed."

Former Google employees are encouraged. "Larry is a visionary, the kind of person that inspires people to do more, be better, reach farther," says Douglas Merrill, Google's chief information officer until 2008. "He would walk around the engineering department and, with just a word or two, guide or redirect projects and leave the developers feeling great about the coaching." Page says one of his goals is to take the decisive leadership style they have shown within their product groups, spread it across the company, and apply it to major decisions. "We've been inspired by a lot of the people who have been operating with more autonomy and clear decision-making authority," he says.

For example, Andy Rubin is as adept at creating mechanical marvels in his home as he is writing the software that runs tablets and mobile phones. His latest invention, produced with several Google colleagues, is "Java the Bot," a wheeled two-armed robot that can roll up to an espresso machine and perform all the steps needed to make a decent cup of coffee. (It's still in development.) Since Google acquired his eight-person start-up, Android, in 2005, Rubin has expended most of his entrepreneurial energy within the Googleplex. His Android platform has pulled off arguably the fastest land grab in tech history, jumping from also-ran to market leader with 26% of the smartphone market, vs. 25% for iPhone (BlackBerry was first, with 33%, but is losing ground). Android's success has made Rubin a model inside Google for how executives can run units autonomously. "We need even more of those," Page says of Android.

Because Rubin's mission to create a mobile operating system was so distinct from the rest of Google's goals, he was given unique leeway in managing his division. He can hire his own team and even controls the landscaping around his office building, which he decorates with supersized ornaments of the desserts (éclair, cupcake) that give versions of Android their name. Google "did a very good job of giving us autonomy," Rubin says. "We can move really, really quickly." Page, Brin, and Schmidt deserve much of the credit for Google's success-but not all of it. "The key to making Google viable was the people they hired in the early days, many of whom are still there and are super-rich," says Steven Levy, author of the forthcoming book In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives. "They are part of the inner circle that makes the big decisions."

Over the past few years, Google has lost a stream of executives to startups, venture capital firms, and, most embarrassingly, Facebook. Sundar Pichai bucked the trend. A vice president for product management in charge of the Chrome browser, Pichai, 38, was recently courted by Twitter, the hot microblogging startup. Pichai won't say whether Google sweetened his compensation, but he confirms that he's not leaving. "I'm staying. I'm happy here," he says. "I look at this as a life journey that I've been on for a long time."

How social media will and won't change Google's world is an ongoing conversation at Google's weekly Execute meetings-and it underscores Larry Page's biggest problem as Google's new CEO. Page values strong, idiosyncratic leaders who know their domains and have their own aggressive agendas. All these rising stars have to work together. The mobile team has to coordinate with the nascent local and e-commerce groups. Rubin's app-based Android vision of the future has to square with Pichai's push for the wide-open Web of Chrome OS; and Singhal's search division has to find common ground with Vic Gundotra and the new czars of social. Can they integrate their plans while satisfying Larry Page's need for speed? At some point, Page may have to dispense with the philosophical discussions, put some limits on the open atmosphere of geeky experimentation, and make some tough decisions. It's not very "Googley." But it's the central challenge of Google 3.0.

What are some of the problems that Google has run into recently as a result of its organizational structure?

Every Monday afternoon at the Googleplex in Mountain View, Calif., more than a dozen of Google's top executives gather in the company's boardroom. The weekly meeting, known as Execute, was launched last summer with a specific mission: to get the near-sovereign leaders of Google's far-flung product groups into a single room and harmonize their disparate initiatives. Google cofounder Sergey Brin runs the meeting, along with new Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and soonto-be-former CEO Eric Schmidt. The unstated goal is to save the search giant from the ossification that can paralyze large corporations.

It won't be easy, because Google is a tech conglomerate, an assemblage of parts that sometimes work at cross-purposes. Among the most important barons at the meeting: Andy Rubin, who oversees the Android operating system for mobile phones; Salar Kamangar, who runs the videosharing site YouTube; and Vic Gundotra, who heads up Google's secret project to combat the social network Facebook. "We needed to get these different product leaders together to find time to talk through all the integration points," says Page during a telephone interview with Bloomberg BusinessWeek minutes before a late-January Execute session. "Every time we increase the size of the company, we need to keep things going to make sure we keep our speed, pace, and passion."

The new weekly ritual-like the surprise announcement on Jan. 20 that Page will take over from Schmidt in April-marks a significant shift in strategy at the world's most famous Internet company. Welcome to Google 3.0. In the 1.0 era, which ran from 1996 to 2001, Page and Brin incubated the company at Stanford University and in a Menlo Park (Calif.) garage. In 2001 they ushered in the triumphant 2.0 era by hiring Schmidt, a tech industry grown-up who'd been CEO of Novell. Now comes the third phase, led by Page and dedicated to rooting out bureaucracy and rediscovering the nimble moves of youth.

Although Google recently reported that fourth-quarter profits jumped 29% over the previous year, its stock rose only 13.7% over the past 12 months and perhaps the most serious rap against the company: that its loosely organized structure is growing unwieldy and counterproductive. The creative chaos inside Google's halls-a decentralized jungle of innovation, as one prominent venture capitalist puts it-once empowered employees to make bold moves, such as creating Gmail, the search-based e-mail system. Other than Android, the culture has recently produced a string of flops, such as Google Buzz, a Twitter clone, and Google Wave, a wonky service that let people collaborate online. Page doesn't explicitly blame those missteps on the company's loosely knit management or the famous troika at the top. Yet he concedes, "We do pay a price for [shared decision making], in terms of speed and people not necessarily knowing where they go to ask questions." His elevation to CEO, he says, "is really a clarification of our roles. I think it will help with our speed."

Former Google employees are encouraged. "Larry is a visionary, the kind of person that inspires people to do more, be better, reach farther," says Douglas Merrill, Google's chief information officer until 2008. "He would walk around the engineering department and, with just a word or two, guide or redirect projects and leave the developers feeling great about the coaching." Page says one of his goals is to take the decisive leadership style they have shown within their product groups, spread it across the company, and apply it to major decisions. "We've been inspired by a lot of the people who have been operating with more autonomy and clear decision-making authority," he says.

For example, Andy Rubin is as adept at creating mechanical marvels in his home as he is writing the software that runs tablets and mobile phones. His latest invention, produced with several Google colleagues, is "Java the Bot," a wheeled two-armed robot that can roll up to an espresso machine and perform all the steps needed to make a decent cup of coffee. (It's still in development.) Since Google acquired his eight-person start-up, Android, in 2005, Rubin has expended most of his entrepreneurial energy within the Googleplex. His Android platform has pulled off arguably the fastest land grab in tech history, jumping from also-ran to market leader with 26% of the smartphone market, vs. 25% for iPhone (BlackBerry was first, with 33%, but is losing ground). Android's success has made Rubin a model inside Google for how executives can run units autonomously. "We need even more of those," Page says of Android.

Because Rubin's mission to create a mobile operating system was so distinct from the rest of Google's goals, he was given unique leeway in managing his division. He can hire his own team and even controls the landscaping around his office building, which he decorates with supersized ornaments of the desserts (éclair, cupcake) that give versions of Android their name. Google "did a very good job of giving us autonomy," Rubin says. "We can move really, really quickly." Page, Brin, and Schmidt deserve much of the credit for Google's success-but not all of it. "The key to making Google viable was the people they hired in the early days, many of whom are still there and are super-rich," says Steven Levy, author of the forthcoming book In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives. "They are part of the inner circle that makes the big decisions."

Over the past few years, Google has lost a stream of executives to startups, venture capital firms, and, most embarrassingly, Facebook. Sundar Pichai bucked the trend. A vice president for product management in charge of the Chrome browser, Pichai, 38, was recently courted by Twitter, the hot microblogging startup. Pichai won't say whether Google sweetened his compensation, but he confirms that he's not leaving. "I'm staying. I'm happy here," he says. "I look at this as a life journey that I've been on for a long time."

How social media will and won't change Google's world is an ongoing conversation at Google's weekly Execute meetings-and it underscores Larry Page's biggest problem as Google's new CEO. Page values strong, idiosyncratic leaders who know their domains and have their own aggressive agendas. All these rising stars have to work together. The mobile team has to coordinate with the nascent local and e-commerce groups. Rubin's app-based Android vision of the future has to square with Pichai's push for the wide-open Web of Chrome OS; and Singhal's search division has to find common ground with Vic Gundotra and the new czars of social. Can they integrate their plans while satisfying Larry Page's need for speed? At some point, Page may have to dispense with the philosophical discussions, put some limits on the open atmosphere of geeky experimentation, and make some tough decisions. It's not very "Googley." But it's the central challenge of Google 3.0.

What are some of the problems that Google has run into recently as a result of its organizational structure?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

17

Is the distribution of authority appropriate for the organization and its activities? Would it be possible to flatten the hierarchy by decentralizing authority and empowering employees?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

18

Discuss the pros and cons of moving to a (a) multidivisional, (b) matrix, and (c) product-team structure to reduce website development time.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

19

What is organizational culture, and how does it affect the way employees behave?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

20

Using the job characteristics model, how motivating do you think the job of a typical employee in this organization is?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

21

What are the principal integrating mechanisms used in the organization? Do they provide sufficient coordination among people and functions? How might they be improved?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

22

Go to the website of Kraft, the food services company ( www.kraft.com ). Click on "Corporate Information" and then explore its brands.

Click on featured brands and look at products like its Oreo cookies. How is Kraft managing its different brands to increase global sales? What do you think are the main challenges Kraft faces in managing its global food business to improve performance?

Click on featured brands and look at products like its Oreo cookies. How is Kraft managing its different brands to increase global sales? What do you think are the main challenges Kraft faces in managing its global food business to improve performance?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

23

With the same or another manager, discuss the distribution of authority in the organization. Does the manager think that decentralizing authority and empowering employees is appropriate.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

24

Using the job characteristics model, discuss how a manager can enlarge or enriched a subordinate's job.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

25

Now that you have analyzed the way this organization is organized, what advice would you give to its managers to help them improve the way it operates?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

26

Some people argue that employees who have worked for an organization for many years have a claim on the organization at least as strong as its shareholders. What do you think of the ethics of this position? Can employees claim to own their jobs if they have contributed significantly to its past success? How does a socially responsible organization behave in this situation?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

27

Interview some employees of an organization. Ask them about the organization's values, norms, the typical characteristics of employees, its ethical values, and socialization practices. Using this information, try to describe the organization's culture and the way it affects the way people and groups behave.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

28

Larry Page's Google 3.0: The company co-founder and his star deputies are trying to root out bureaucracy and rediscover the nimble moves of youth.

Every Monday afternoon at the Googleplex in Mountain View, Calif., more than a dozen of Google's top executives gather in the company's boardroom. The weekly meeting, known as Execute, was launched last summer with a specific mission: to get the near-sovereign leaders of Google's far-flung product groups into a single room and harmonize their disparate initiatives. Google cofounder Sergey Brin runs the meeting, along with new Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and soonto-be-former CEO Eric Schmidt. The unstated goal is to save the search giant from the ossification that can paralyze large corporations.

It won't be easy, because Google is a tech conglomerate, an assemblage of parts that sometimes work at cross-purposes. Among the most important barons at the meeting: Andy Rubin, who oversees the Android operating system for mobile phones; Salar Kamangar, who runs the videosharing site YouTube; and Vic Gundotra, who heads up Google's secret project to combat the social network Facebook. "We needed to get these different product leaders together to find time to talk through all the integration points," says Page during a telephone interview with Bloomberg BusinessWeek minutes before a late-January Execute session. "Every time we increase the size of the company, we need to keep things going to make sure we keep our speed, pace, and passion."

The new weekly ritual-like the surprise announcement on Jan. 20 that Page will take over from Schmidt in April-marks a significant shift in strategy at the world's most famous Internet company. Welcome to Google 3.0. In the 1.0 era, which ran from 1996 to 2001, Page and Brin incubated the company at Stanford University and in a Menlo Park (Calif.) garage. In 2001 they ushered in the triumphant 2.0 era by hiring Schmidt, a tech industry grown-up who'd been CEO of Novell. Now comes the third phase, led by Page and dedicated to rooting out bureaucracy and rediscovering the nimble moves of youth.

Although Google recently reported that fourth-quarter profits jumped 29% over the previous year, its stock rose only 13.7% over the past 12 months and perhaps the most serious rap against the company: that its loosely organized structure is growing unwieldy and counterproductive. The creative chaos inside Google's halls-a decentralized jungle of innovation, as one prominent venture capitalist puts it-once empowered employees to make bold moves, such as creating Gmail, the search-based e-mail system. Other than Android, the culture has recently produced a string of flops, such as Google Buzz, a Twitter clone, and Google Wave, a wonky service that let people collaborate online. Page doesn't explicitly blame those missteps on the company's loosely knit management or the famous troika at the top. Yet he concedes, "We do pay a price for [shared decision making], in terms of speed and people not necessarily knowing where they go to ask questions." His elevation to CEO, he says, "is really a clarification of our roles. I think it will help with our speed."

Former Google employees are encouraged. "Larry is a visionary, the kind of person that inspires people to do more, be better, reach farther," says Douglas Merrill, Google's chief information officer until 2008. "He would walk around the engineering department and, with just a word or two, guide or redirect projects and leave the developers feeling great about the coaching." Page says one of his goals is to take the decisive leadership style they have shown within their product groups, spread it across the company, and apply it to major decisions. "We've been inspired by a lot of the people who have been operating with more autonomy and clear decision-making authority," he says.

For example, Andy Rubin is as adept at creating mechanical marvels in his home as he is writing the software that runs tablets and mobile phones. His latest invention, produced with several Google colleagues, is "Java the Bot," a wheeled two-armed robot that can roll up to an espresso machine and perform all the steps needed to make a decent cup of coffee. (It's still in development.) Since Google acquired his eight-person start-up, Android, in 2005, Rubin has expended most of his entrepreneurial energy within the Googleplex. His Android platform has pulled off arguably the fastest land grab in tech history, jumping from also-ran to market leader with 26% of the smartphone market, vs. 25% for iPhone (BlackBerry was first, with 33%, but is losing ground). Android's success has made Rubin a model inside Google for how executives can run units autonomously. "We need even more of those," Page says of Android.

Because Rubin's mission to create a mobile operating system was so distinct from the rest of Google's goals, he was given unique leeway in managing his division. He can hire his own team and even controls the landscaping around his office building, which he decorates with supersized ornaments of the desserts (éclair, cupcake) that give versions of Android their name. Google "did a very good job of giving us autonomy," Rubin says. "We can move really, really quickly." Page, Brin, and Schmidt deserve much of the credit for Google's success-but not all of it. "The key to making Google viable was the people they hired in the early days, many of whom are still there and are super-rich," says Steven Levy, author of the forthcoming book In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives. "They are part of the inner circle that makes the big decisions."

Over the past few years, Google has lost a stream of executives to startups, venture capital firms, and, most embarrassingly, Facebook. Sundar Pichai bucked the trend. A vice president for product management in charge of the Chrome browser, Pichai, 38, was recently courted by Twitter, the hot microblogging startup. Pichai won't say whether Google sweetened his compensation, but he confirms that he's not leaving. "I'm staying. I'm happy here," he says. "I look at this as a life journey that I've been on for a long time."

How social media will and won't change Google's world is an ongoing conversation at Google's weekly Execute meetings-and it underscores Larry Page's biggest problem as Google's new CEO. Page values strong, idiosyncratic leaders who know their domains and have their own aggressive agendas. All these rising stars have to work together. The mobile team has to coordinate with the nascent local and e-commerce groups. Rubin's app-based Android vision of the future has to square with Pichai's push for the wide-open Web of Chrome OS; and Singhal's search division has to find common ground with Vic Gundotra and the new czars of social. Can they integrate their plans while satisfying Larry Page's need for speed? At some point, Page may have to dispense with the philosophical discussions, put some limits on the open atmosphere of geeky experimentation, and make some tough decisions. It's not very "Googley." But it's the central challenge of Google 3.0.

In what ways do you think Larry page needs to change Google's structure to make it work more effectively?

Every Monday afternoon at the Googleplex in Mountain View, Calif., more than a dozen of Google's top executives gather in the company's boardroom. The weekly meeting, known as Execute, was launched last summer with a specific mission: to get the near-sovereign leaders of Google's far-flung product groups into a single room and harmonize their disparate initiatives. Google cofounder Sergey Brin runs the meeting, along with new Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and soonto-be-former CEO Eric Schmidt. The unstated goal is to save the search giant from the ossification that can paralyze large corporations.

It won't be easy, because Google is a tech conglomerate, an assemblage of parts that sometimes work at cross-purposes. Among the most important barons at the meeting: Andy Rubin, who oversees the Android operating system for mobile phones; Salar Kamangar, who runs the videosharing site YouTube; and Vic Gundotra, who heads up Google's secret project to combat the social network Facebook. "We needed to get these different product leaders together to find time to talk through all the integration points," says Page during a telephone interview with Bloomberg BusinessWeek minutes before a late-January Execute session. "Every time we increase the size of the company, we need to keep things going to make sure we keep our speed, pace, and passion."

The new weekly ritual-like the surprise announcement on Jan. 20 that Page will take over from Schmidt in April-marks a significant shift in strategy at the world's most famous Internet company. Welcome to Google 3.0. In the 1.0 era, which ran from 1996 to 2001, Page and Brin incubated the company at Stanford University and in a Menlo Park (Calif.) garage. In 2001 they ushered in the triumphant 2.0 era by hiring Schmidt, a tech industry grown-up who'd been CEO of Novell. Now comes the third phase, led by Page and dedicated to rooting out bureaucracy and rediscovering the nimble moves of youth.

Although Google recently reported that fourth-quarter profits jumped 29% over the previous year, its stock rose only 13.7% over the past 12 months and perhaps the most serious rap against the company: that its loosely organized structure is growing unwieldy and counterproductive. The creative chaos inside Google's halls-a decentralized jungle of innovation, as one prominent venture capitalist puts it-once empowered employees to make bold moves, such as creating Gmail, the search-based e-mail system. Other than Android, the culture has recently produced a string of flops, such as Google Buzz, a Twitter clone, and Google Wave, a wonky service that let people collaborate online. Page doesn't explicitly blame those missteps on the company's loosely knit management or the famous troika at the top. Yet he concedes, "We do pay a price for [shared decision making], in terms of speed and people not necessarily knowing where they go to ask questions." His elevation to CEO, he says, "is really a clarification of our roles. I think it will help with our speed."

Former Google employees are encouraged. "Larry is a visionary, the kind of person that inspires people to do more, be better, reach farther," says Douglas Merrill, Google's chief information officer until 2008. "He would walk around the engineering department and, with just a word or two, guide or redirect projects and leave the developers feeling great about the coaching." Page says one of his goals is to take the decisive leadership style they have shown within their product groups, spread it across the company, and apply it to major decisions. "We've been inspired by a lot of the people who have been operating with more autonomy and clear decision-making authority," he says.

For example, Andy Rubin is as adept at creating mechanical marvels in his home as he is writing the software that runs tablets and mobile phones. His latest invention, produced with several Google colleagues, is "Java the Bot," a wheeled two-armed robot that can roll up to an espresso machine and perform all the steps needed to make a decent cup of coffee. (It's still in development.) Since Google acquired his eight-person start-up, Android, in 2005, Rubin has expended most of his entrepreneurial energy within the Googleplex. His Android platform has pulled off arguably the fastest land grab in tech history, jumping from also-ran to market leader with 26% of the smartphone market, vs. 25% for iPhone (BlackBerry was first, with 33%, but is losing ground). Android's success has made Rubin a model inside Google for how executives can run units autonomously. "We need even more of those," Page says of Android.

Because Rubin's mission to create a mobile operating system was so distinct from the rest of Google's goals, he was given unique leeway in managing his division. He can hire his own team and even controls the landscaping around his office building, which he decorates with supersized ornaments of the desserts (éclair, cupcake) that give versions of Android their name. Google "did a very good job of giving us autonomy," Rubin says. "We can move really, really quickly." Page, Brin, and Schmidt deserve much of the credit for Google's success-but not all of it. "The key to making Google viable was the people they hired in the early days, many of whom are still there and are super-rich," says Steven Levy, author of the forthcoming book In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives. "They are part of the inner circle that makes the big decisions."

Over the past few years, Google has lost a stream of executives to startups, venture capital firms, and, most embarrassingly, Facebook. Sundar Pichai bucked the trend. A vice president for product management in charge of the Chrome browser, Pichai, 38, was recently courted by Twitter, the hot microblogging startup. Pichai won't say whether Google sweetened his compensation, but he confirms that he's not leaving. "I'm staying. I'm happy here," he says. "I look at this as a life journey that I've been on for a long time."

How social media will and won't change Google's world is an ongoing conversation at Google's weekly Execute meetings-and it underscores Larry Page's biggest problem as Google's new CEO. Page values strong, idiosyncratic leaders who know their domains and have their own aggressive agendas. All these rising stars have to work together. The mobile team has to coordinate with the nascent local and e-commerce groups. Rubin's app-based Android vision of the future has to square with Pichai's push for the wide-open Web of Chrome OS; and Singhal's search division has to find common ground with Vic Gundotra and the new czars of social. Can they integrate their plans while satisfying Larry Page's need for speed? At some point, Page may have to dispense with the philosophical discussions, put some limits on the open atmosphere of geeky experimentation, and make some tough decisions. It's not very "Googley." But it's the central challenge of Google 3.0.

In what ways do you think Larry page needs to change Google's structure to make it work more effectively?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

29

Interview some employees of an organization and ask them about the organization's values and norms, the typical characteristics of employees, and the organization's ethical values and socialization practices. Using this information, try to describe the organization's culture and the way it affects how people and groups behave.

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck

30

Which of these structures do you think is most appropriate and why?

Unlock Deck

Unlock for access to all 30 flashcards in this deck.

Unlock Deck

k this deck