Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945 Exercise 3

Why Does a Cell's Disposal of Damaged Proteins Consume Energy?

Much of modern biology is devoted to learning how cells build things-how the information encoded in DNA is used by cells to manufacture the proteins that make us what we are. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded in 2004 to researchers for their discovery of how the opposite, less glamorous process works: How cells break down and recycle proteins that are damaged or have outlived their usefulness.

It turns out that a cell's recycling of proteins is much more than just "taking out the trash." Particular proteins are removed, often quite quickly, and cells use such targeted removals to control a lot of their activities, timing when a cell carries out particular functions, when it divides, and even when it dies. Of the 25,000 genes in your DNA, about 1,000 take part in this protein recycling system.

Our understanding of how this system works begins with a puzzle first noted in the 1950s. Most enzymes that break down proteins, including those that digest food, do not need energy to work. But a cell's recycling of its own proteins does consume energy. Researchers had no idea why energy was needed.

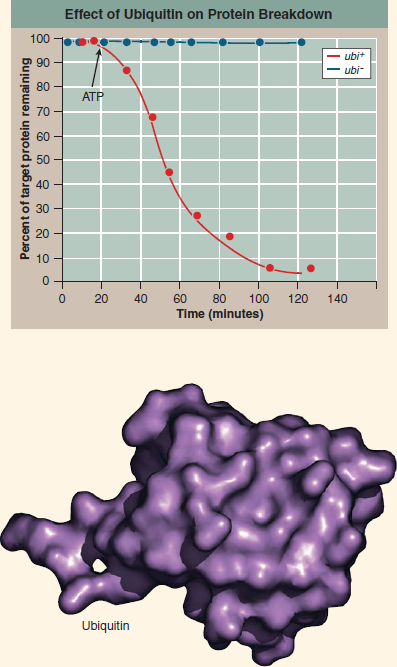

The answer to this puzzle came from an unexpected direction. In 1975 scientists discovered a small protein in calves' brains consisting of just 76 amino acids. Soon they realized that exactly the same protein is found in all eukaryotes, from yeasts to humans. They called this ubiquitous ("found everywhere") protein ubiquitin.

In the early 1980s researchers figured out that ubiquitin is a label that the cell attaches to proteins to mark them for destruction, a sort of molecular "kiss of death." The process of attaching ubiquitin takes energy, solving the puzzle of why protein recycling requires energy. The tagged proteins are taken to a barrel-shaped chamber in the cell's cytoplasm called a proteasome, which slices the proteins into bits that are then recycled by the cell into new protein.

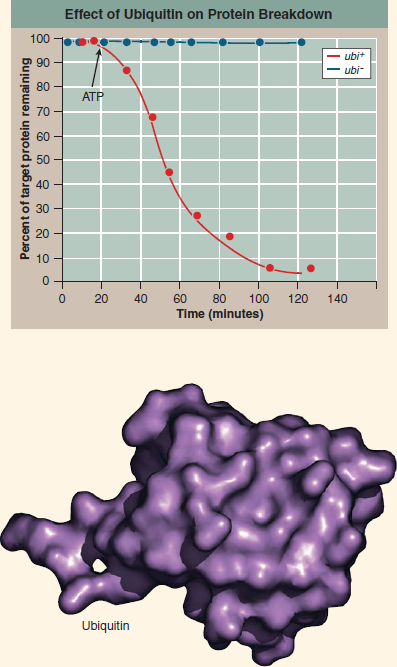

The graph above displays the sort of protein-recycling experiment that revealed ubiquitin's key role. The experiment monitors levels of a particular protein involved in cell division (the "target" protein) within human cells growing in culture in a laboratory flask. Two cultures are monitored in side-by-side experiments: In the culture indicated by red dots, cells contain functional copies of the ubiquitin gene ( ubi + ); in the culture indicated by blue dots, the ubiquitin gene has been deleted from the DNA ( ubi - ). After 20 minutes, energy in the form of ATP is made available to the growing cells, which until then had been energy-starved.

Making Inferences How does this culture differ from the other? Why might ATP stimulate removal of target protein from this culture but not the other?

Much of modern biology is devoted to learning how cells build things-how the information encoded in DNA is used by cells to manufacture the proteins that make us what we are. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded in 2004 to researchers for their discovery of how the opposite, less glamorous process works: How cells break down and recycle proteins that are damaged or have outlived their usefulness.

It turns out that a cell's recycling of proteins is much more than just "taking out the trash." Particular proteins are removed, often quite quickly, and cells use such targeted removals to control a lot of their activities, timing when a cell carries out particular functions, when it divides, and even when it dies. Of the 25,000 genes in your DNA, about 1,000 take part in this protein recycling system.

Our understanding of how this system works begins with a puzzle first noted in the 1950s. Most enzymes that break down proteins, including those that digest food, do not need energy to work. But a cell's recycling of its own proteins does consume energy. Researchers had no idea why energy was needed.

The answer to this puzzle came from an unexpected direction. In 1975 scientists discovered a small protein in calves' brains consisting of just 76 amino acids. Soon they realized that exactly the same protein is found in all eukaryotes, from yeasts to humans. They called this ubiquitous ("found everywhere") protein ubiquitin.

In the early 1980s researchers figured out that ubiquitin is a label that the cell attaches to proteins to mark them for destruction, a sort of molecular "kiss of death." The process of attaching ubiquitin takes energy, solving the puzzle of why protein recycling requires energy. The tagged proteins are taken to a barrel-shaped chamber in the cell's cytoplasm called a proteasome, which slices the proteins into bits that are then recycled by the cell into new protein.

The graph above displays the sort of protein-recycling experiment that revealed ubiquitin's key role. The experiment monitors levels of a particular protein involved in cell division (the "target" protein) within human cells growing in culture in a laboratory flask. Two cultures are monitored in side-by-side experiments: In the culture indicated by red dots, cells contain functional copies of the ubiquitin gene ( ubi + ); in the culture indicated by blue dots, the ubiquitin gene has been deleted from the DNA ( ubi - ). After 20 minutes, energy in the form of ATP is made available to the growing cells, which until then had been energy-starved.

Making Inferences How does this culture differ from the other? Why might ATP stimulate removal of target protein from this culture but not the other?

Explanation

The culture that has the presence of the...

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255