Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945 Exercise 2

Do Enzymes Physically Attach to Their Substrates?

When scientists first began to examine the chemical activities of organisms, no one knew that biochemical reactions were catalyzed by enzymes. The first enzyme was discovered in 1833 by French chemist Anselme Payen. He was studying how beer is made from barley: First barley is pressed and gently heated so its starches break down into simple two-sugar units; then yeasts convert these units into ethanol. Payen found that the initial breakdown requires a chemical factor that is not alive and that does not seem to be used up during the process-a catalyst. He called this first enzyme diastase (we call it amylase today).

Did this catalyst operate at a distance, increasing reaction rate all around it, much as raising the temperature of nearby molecules might do? Or did it operate in physical contact, actually attaching to the molecules whose reaction it catalyzed (its "substrate")?

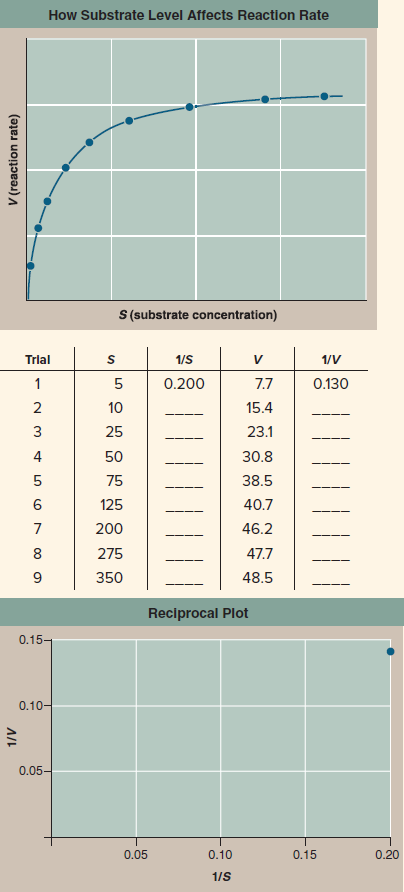

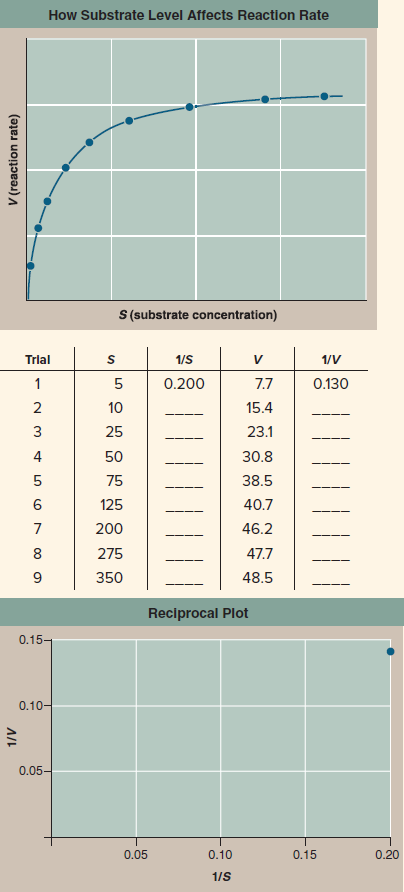

Henri. He saw that the hypothesis that an enzyme physically binds to its substrate makes a clear and testable prediction: In a solution of substrate and enzyme, there must be a maximum reaction rate. When all the enzyme molecules are working full tilt, the reaction simply cannot go any faster, no matter how much more substrate you add to the solution. To test this prediction, Henri carried out the experiment whose results you see in the graph, measuring the reaction rate ( V ) of diastase at different substrate concentrations ( S ).

Drawing Conclusions Does this result provide support for the hypothesis that an enzyme binds physically to its substrate? Explain. If the hypothesis were incorrect, what would you expect the graph to look like?

When scientists first began to examine the chemical activities of organisms, no one knew that biochemical reactions were catalyzed by enzymes. The first enzyme was discovered in 1833 by French chemist Anselme Payen. He was studying how beer is made from barley: First barley is pressed and gently heated so its starches break down into simple two-sugar units; then yeasts convert these units into ethanol. Payen found that the initial breakdown requires a chemical factor that is not alive and that does not seem to be used up during the process-a catalyst. He called this first enzyme diastase (we call it amylase today).

Did this catalyst operate at a distance, increasing reaction rate all around it, much as raising the temperature of nearby molecules might do? Or did it operate in physical contact, actually attaching to the molecules whose reaction it catalyzed (its "substrate")?

Henri. He saw that the hypothesis that an enzyme physically binds to its substrate makes a clear and testable prediction: In a solution of substrate and enzyme, there must be a maximum reaction rate. When all the enzyme molecules are working full tilt, the reaction simply cannot go any faster, no matter how much more substrate you add to the solution. To test this prediction, Henri carried out the experiment whose results you see in the graph, measuring the reaction rate ( V ) of diastase at different substrate concentrations ( S ).

Drawing Conclusions Does this result provide support for the hypothesis that an enzyme binds physically to its substrate? Explain. If the hypothesis were incorrect, what would you expect the graph to look like?

Explanation

It can be concluded from the results of ...

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255