Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945 Exercise 3

Why Do Human Cells Age?

Human cells appear to have built-in life spans. In 1961 cell biologist Leonard Hayflick reported the startling result that skin cells growing in tissue culture, such as those growing in culture flasks in the photo below, will divide only a certain number of times. After about 50 population doublings, cell division stops (a doubling is a round of cell division producing two daughter cells for each dividing cell; for example, going from a population of 30 cells to 60 cells). If a cell sample is taken after 20 doublings and frozen, when thawed it resumes growth for 30 more doublings and then stops. An explanation of the "Hayflick limit" was suggested in 1986 when researchers first glimpsed an extra length of DNA at the end of chromosomes. Dubbed telomeres , these lengths proved to be composed of the simple DNA sequence TTAGGG, repeated nearly a thousand times. Importantly, telomeres were found to be substantially shorter in the cells of older body tissues. This led to the hypothesis that a run of some 16 TTAGGGs was where the DNA replicating enzyme, called polymerase, first sat down on the DNA (16 TTAGGGs being the size of the enzyme's "footprint"), and because of being its docking spot, the polymerase was unable to copy that bit. Thus, a 100-base portion of the telomere was lost by a chromosome during each doubling as DNA replicated. Eventually, after some 50 doubling cycles, each with a round of DNA replication, the telomere would be used up and there would be no place for the DNA replication enzyme to sit. The cell line would then enter senescence, no longer able to proliferate.

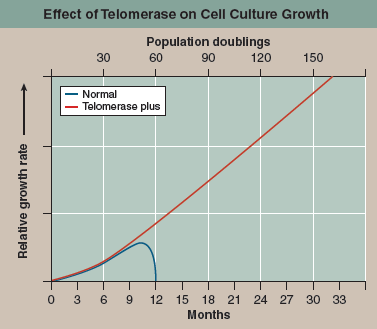

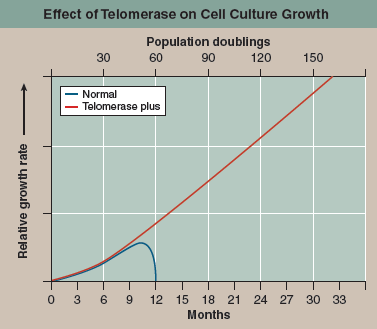

This hypothesis was tested in 1998. Using genetic engineering, researchers transferred into newly established human cell cultures a gene that leads to expression of an enzyme called telomerase that all cells possess but no body cell uses. This enzyme adds TTAGGG sequences back to the end of telomeres, in effect rebuilding the lost portions of the telomere. Laboratory cultures of cell lines with (telomerase plus) and without (normal) this gene were then monitored for many generations. The graph above displays the results.

Making Inferences After 9 population doublings, would the rate of cell division be different between the two cultures? after 15? Why?

Human cells appear to have built-in life spans. In 1961 cell biologist Leonard Hayflick reported the startling result that skin cells growing in tissue culture, such as those growing in culture flasks in the photo below, will divide only a certain number of times. After about 50 population doublings, cell division stops (a doubling is a round of cell division producing two daughter cells for each dividing cell; for example, going from a population of 30 cells to 60 cells). If a cell sample is taken after 20 doublings and frozen, when thawed it resumes growth for 30 more doublings and then stops. An explanation of the "Hayflick limit" was suggested in 1986 when researchers first glimpsed an extra length of DNA at the end of chromosomes. Dubbed telomeres , these lengths proved to be composed of the simple DNA sequence TTAGGG, repeated nearly a thousand times. Importantly, telomeres were found to be substantially shorter in the cells of older body tissues. This led to the hypothesis that a run of some 16 TTAGGGs was where the DNA replicating enzyme, called polymerase, first sat down on the DNA (16 TTAGGGs being the size of the enzyme's "footprint"), and because of being its docking spot, the polymerase was unable to copy that bit. Thus, a 100-base portion of the telomere was lost by a chromosome during each doubling as DNA replicated. Eventually, after some 50 doubling cycles, each with a round of DNA replication, the telomere would be used up and there would be no place for the DNA replication enzyme to sit. The cell line would then enter senescence, no longer able to proliferate.

This hypothesis was tested in 1998. Using genetic engineering, researchers transferred into newly established human cell cultures a gene that leads to expression of an enzyme called telomerase that all cells possess but no body cell uses. This enzyme adds TTAGGG sequences back to the end of telomeres, in effect rebuilding the lost portions of the telomere. Laboratory cultures of cell lines with (telomerase plus) and without (normal) this gene were then monitored for many generations. The graph above displays the results.

Making Inferences After 9 population doublings, would the rate of cell division be different between the two cultures? after 15? Why?

Explanation

The rate of cell is division is same in ...

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255