Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Edition 5ISBN: 978-0078096945 Exercise 2

Are Extinction Rates Constant?

Since the time of the dinosaurs, the number of living species has risen steadily. Today, for example, there are over 700 families of marine animals, containing thousands of described species.

Along the way, however, have been a number of major setbacks, termed mass extinctions, in which the number of species has greatly decreased. Five major mass extinctions have been identified, the most severe of which occurred at the end of the Permian Period, approximately 225 million years ago, at which time more than half of all families and as many as 96% of all species may have perished.

The most famous and well-studied extinction occurred 65 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous Period. At that time, dinosaurs and a variety of other organisms went extinct, most likely due to the collision of a large meteor with earth. This mass extinction did have one positive effect, though: With the disappearance of dinosaurs, mammals, which previously had been relatively small and inconspicuous, quickly experienced a vast evolutionary radiation that ultimately produced a wide variety of organisms, including elephants, tigers, whales, and humans. Indeed, a general observation is that biological diversity tends to rebound quickly after mass extinctions, reaching comparable levels of species richness, even if the organisms making up that diversity are not the same.

Today, the number of species in the world is decreasing at an alarming rate due to human activities. We are living during a sixth mass extinction. Some biologists estimate that species are becoming extinct at a rate not seen on earth since the Cretaceous mass extinction.

One thing that the Cretaceous mass extinction and the present-day mass extinction share is that species are becoming extinct for reasons that have nothing to do with what they themselves are like. Is this generally true of all extinctions, or are mass extinctions a special case?

Evolutionist Lee Van Valen put forth the hypothesis in 1973 that extinction is indeed usually due to random events unrelated to a species's particular adaptations. If this is in fact the case, then the likelihood that a species will go extinct would be expected to be virtually constant, when viewed over long periods of time.

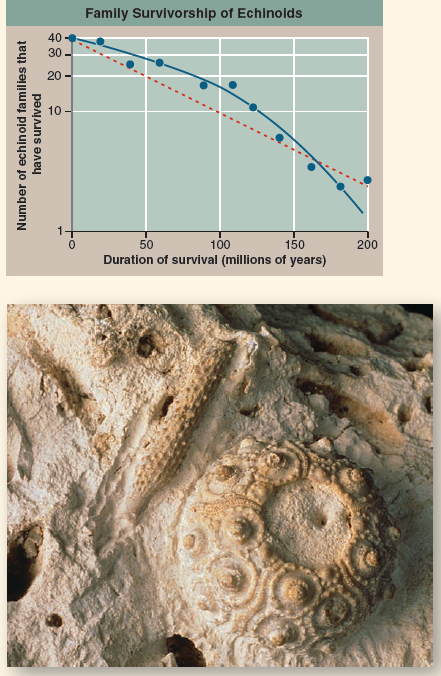

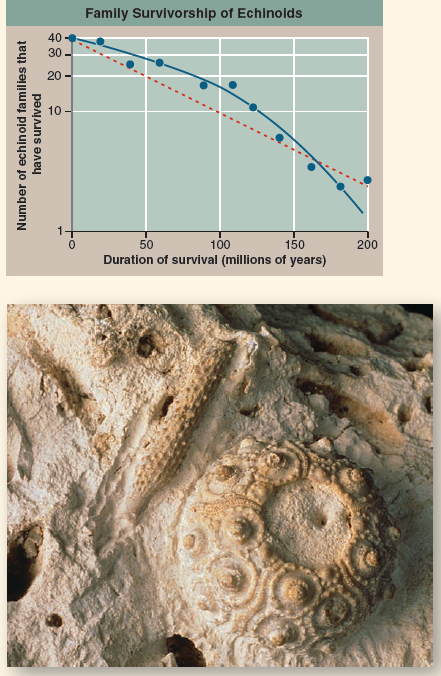

Van Valen's hypothesis has been tested by evolutionary biologists for a variety of animal groups. One of the most complete fossil records available for such a test is that of marine echinoids (sea urchins and sand dollars). The fossil echinoid you see in the photo, genus Cidaris , is from the Cretaceous some 75 million years ago. In the graph above it, you see an examination of the 200 million year fossil record of echinoids. Data are presented as the number of echinoid families that have survived for over a period of 200 million years (the blue dots on the graph), estimated from the fossil record. The red dashed line shows a theoretical constant extinction rate, as postulated by Van Valen. The blue line is a "best-fit" curve determined by statistical regression analysis of the family number estimates.

Making Inferences Over the 200 million year fossil record of echinoids, which of the two lines best represents the data?

Since the time of the dinosaurs, the number of living species has risen steadily. Today, for example, there are over 700 families of marine animals, containing thousands of described species.

Along the way, however, have been a number of major setbacks, termed mass extinctions, in which the number of species has greatly decreased. Five major mass extinctions have been identified, the most severe of which occurred at the end of the Permian Period, approximately 225 million years ago, at which time more than half of all families and as many as 96% of all species may have perished.

The most famous and well-studied extinction occurred 65 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous Period. At that time, dinosaurs and a variety of other organisms went extinct, most likely due to the collision of a large meteor with earth. This mass extinction did have one positive effect, though: With the disappearance of dinosaurs, mammals, which previously had been relatively small and inconspicuous, quickly experienced a vast evolutionary radiation that ultimately produced a wide variety of organisms, including elephants, tigers, whales, and humans. Indeed, a general observation is that biological diversity tends to rebound quickly after mass extinctions, reaching comparable levels of species richness, even if the organisms making up that diversity are not the same.

Today, the number of species in the world is decreasing at an alarming rate due to human activities. We are living during a sixth mass extinction. Some biologists estimate that species are becoming extinct at a rate not seen on earth since the Cretaceous mass extinction.

One thing that the Cretaceous mass extinction and the present-day mass extinction share is that species are becoming extinct for reasons that have nothing to do with what they themselves are like. Is this generally true of all extinctions, or are mass extinctions a special case?

Evolutionist Lee Van Valen put forth the hypothesis in 1973 that extinction is indeed usually due to random events unrelated to a species's particular adaptations. If this is in fact the case, then the likelihood that a species will go extinct would be expected to be virtually constant, when viewed over long periods of time.

Van Valen's hypothesis has been tested by evolutionary biologists for a variety of animal groups. One of the most complete fossil records available for such a test is that of marine echinoids (sea urchins and sand dollars). The fossil echinoid you see in the photo, genus Cidaris , is from the Cretaceous some 75 million years ago. In the graph above it, you see an examination of the 200 million year fossil record of echinoids. Data are presented as the number of echinoid families that have survived for over a period of 200 million years (the blue dots on the graph), estimated from the fossil record. The red dashed line shows a theoretical constant extinction rate, as postulated by Van Valen. The blue line is a "best-fit" curve determined by statistical regression analysis of the family number estimates.

Making Inferences Over the 200 million year fossil record of echinoids, which of the two lines best represents the data?

Explanation

The Lee Van Valen is an evolutionist, wh...

Essentials of the Living World 5th Edition by George Johnson

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255