Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022 Exercise 39

The Consumer Price Index and Its Biases

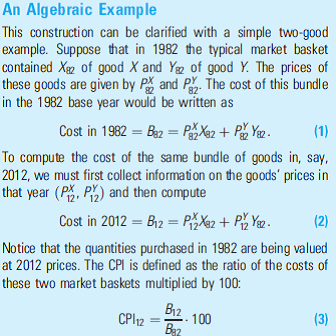

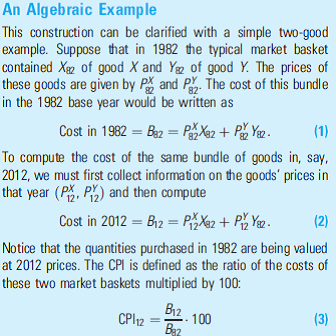

One of the principal measures of inflation in the United States is provided by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is published monthly by the U.S. Department of Labor. To construct the CPI, the Bureau of Labor Statistics first defines a typical market basket of commodities purchased by consumers in a base year (1982 is the year currently used). Then data are collected every month about how much this market basket of commodities currently costs the consumer. The ratio of the current cost to the bundle's original cost (in 1982) is then published as the current value of the CPI. The rate of change in this index between two periods is reported to be the rate of inflation.

The rate of inflation can be computed from this index. For example, if the same market basket of items that cost $100 in 1982 costs $230 in 2012, the value of the CPI would be 230 and we would say there had been a 130 percent increase in prices over this 30-year period. It might (probably incorrectly) be said that people would need a 130 percent increase in nominal 1982 income to enjoy the same standard of living in 2012 that they had in 1982. Cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) in Social Security benefits and in many job agreements are calculated in precisely this way. Unfortunately, this approach poses a number of problems.

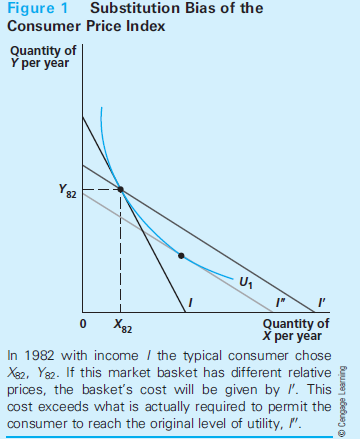

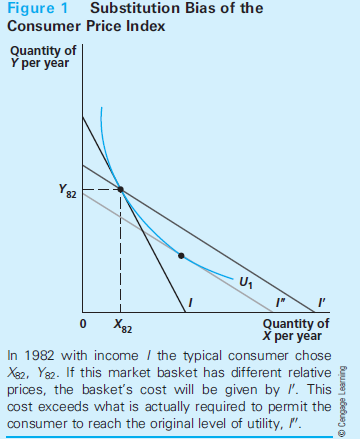

Substitution Bias in the CPI One conceptual problem with the preceding calculation is that it assumes that people who are faced with year 2012 prices will continue to demand the same basket of commodities that they consumed in 1982. This treatment makes no allowance for substitutions among commodities in response to changing prices. The calculation may overstate the decline in purchasing power that inflation has caused because it takes no account of how people will seek to get the most utility for their incomes when prices change.

In Figure 1, for example, a typical individual initially is consuming X 82 , Y 82. Presumably, this choice provides maximum utility (U1), given his or her budget constraint in 1982 (which we call I). Suppose that by 2012 relative prices have changed in such a way that good Y becomes relatively more expensive. This would make the budget constraint flatter than it was in 1982. Using these new prices, the CPI calculates what X 82 , Y 82 would cost. This cost would be reflected by the budget constraint I', which is flatter than I (to reflect the changed prices) and passes through the 1982 consumption point. As the figure makes clear, the erosion in purchasing power that has occurred is overstated. With I', this typical

person could now reach a higher utility level than could have been attained in 1982. The CPI overstates the decline in purchasing power that has occurred.

A true measure of inflation would be provided by evaluating an income level, say, I", which reflects the new prices but just permits the individual to remain on U 1. This would take account of the substitution in consumption that people might make in response to changing relative prices (they consume more X and less Y in moving along U 1 ). Unfortunately, adjusting the CPI to take such substitutions into account is a difficult task-primarily because the typical consumer's utility function cannot be measured accurately.

New Product and Quality Bias

The introduction of new or improved products introduces a similar bias in the CPI. New products usually experience sharp declines in prices and rapidly growing rates of acceptance by consumers (consider cell phones or DVDs, for example). If these goods are not included in the CPI market basket, a major source of welfare gain for consumers will have been omitted. Of course, the CPI market basket is updated every few years to permit new goods to be included. But that rate of revision is often insufficient for rapidly changing consumer markets. See Application 3.4: Valuing New Goods for one approach to how new goods might be valued.

Adjusting the CPI for the improving quality poses similar difficulties. In many cases, the price of a specific consumer good will stay relatively constant from year to year, but more recent models of the good will be much better. For example, a good-quality laptop computer has had a price in the $500?$1,500 price range for many years. But this year's version is much more powerful than the models available, say, five or ten years ago. In effect, the price of a fixed-quality laptop has fallen dramatically, but this will not be apparent when the CPI shoppers are told to purchase a "new laptop." Statisticians who compute the CPI have grappled with this problem for many years and have come up with a variety of ingenious solutions (including the use of "hedonic price" models-see Application 1A.1: How Does Zillow.com Do It?). Still, many economists believe that the CPI continues to miss many improvements in goods' quality.

Outlet Bias

Finally, the fact that the Bureau of Labor Statistics sends buyers to the same retail outlets each month may overstate inflation. Actual consumers tend to seek out temporary sales or other bargains. They shop where they can make their money go the farthest. In recent years, this has meant shopping at giant discount stores such as Sam's Club or Costco rather than at traditional outlets. The CPI as currently constructed does not take such price-reducing strategies into account.

Consequences of the Biases

Measuring all these biases and devising a better CPI to take them into account is no easy task. Indeed, because the CPI is so widely used as "the" measure of inflation, any change can become a very hot political controversy. Still, there is general agreement that the current CPI may overstate actual increases in the cost of living by as much as 0:75 percent to 1:0 percent per year.1 By some estimates, correction of the index could reduce projected federal spending by as much as a half trillion dollars over a 10-year period. Hence, some politicians have proposed caps on COLAs in government programs. These suggestions have been very controversial, and none has so far been enacted. In private contracts, however, the upward biases in the CPI are frequently recognized. Few private COLAs provide full offsets to inflation as measured by the CPI.

There are many aspects of government policy where it is necessary to adjust for inflation. Some of these include (1) adjusting Social Security benefits, (2) changing cutoff points for income tax brackets, and (3) adjusting the values of "inflation-protected" bonds. How should the government choose a price index to make all of these adjustments? For example, many economists have suggested using a "chained" price index in which commodity bundles are changed every month to address substitution bias. According to some estimates this would reduce adjustments for inflation by about 0:25 percent per year. Would this be fair to elderly Social Security recipients who typically spend much more on (highly inflationary) medical care than do younger consumers?

One of the principal measures of inflation in the United States is provided by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is published monthly by the U.S. Department of Labor. To construct the CPI, the Bureau of Labor Statistics first defines a typical market basket of commodities purchased by consumers in a base year (1982 is the year currently used). Then data are collected every month about how much this market basket of commodities currently costs the consumer. The ratio of the current cost to the bundle's original cost (in 1982) is then published as the current value of the CPI. The rate of change in this index between two periods is reported to be the rate of inflation.

The rate of inflation can be computed from this index. For example, if the same market basket of items that cost $100 in 1982 costs $230 in 2012, the value of the CPI would be 230 and we would say there had been a 130 percent increase in prices over this 30-year period. It might (probably incorrectly) be said that people would need a 130 percent increase in nominal 1982 income to enjoy the same standard of living in 2012 that they had in 1982. Cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) in Social Security benefits and in many job agreements are calculated in precisely this way. Unfortunately, this approach poses a number of problems.

Substitution Bias in the CPI One conceptual problem with the preceding calculation is that it assumes that people who are faced with year 2012 prices will continue to demand the same basket of commodities that they consumed in 1982. This treatment makes no allowance for substitutions among commodities in response to changing prices. The calculation may overstate the decline in purchasing power that inflation has caused because it takes no account of how people will seek to get the most utility for their incomes when prices change.

In Figure 1, for example, a typical individual initially is consuming X 82 , Y 82. Presumably, this choice provides maximum utility (U1), given his or her budget constraint in 1982 (which we call I). Suppose that by 2012 relative prices have changed in such a way that good Y becomes relatively more expensive. This would make the budget constraint flatter than it was in 1982. Using these new prices, the CPI calculates what X 82 , Y 82 would cost. This cost would be reflected by the budget constraint I', which is flatter than I (to reflect the changed prices) and passes through the 1982 consumption point. As the figure makes clear, the erosion in purchasing power that has occurred is overstated. With I', this typical

person could now reach a higher utility level than could have been attained in 1982. The CPI overstates the decline in purchasing power that has occurred.

A true measure of inflation would be provided by evaluating an income level, say, I", which reflects the new prices but just permits the individual to remain on U 1. This would take account of the substitution in consumption that people might make in response to changing relative prices (they consume more X and less Y in moving along U 1 ). Unfortunately, adjusting the CPI to take such substitutions into account is a difficult task-primarily because the typical consumer's utility function cannot be measured accurately.

New Product and Quality Bias

The introduction of new or improved products introduces a similar bias in the CPI. New products usually experience sharp declines in prices and rapidly growing rates of acceptance by consumers (consider cell phones or DVDs, for example). If these goods are not included in the CPI market basket, a major source of welfare gain for consumers will have been omitted. Of course, the CPI market basket is updated every few years to permit new goods to be included. But that rate of revision is often insufficient for rapidly changing consumer markets. See Application 3.4: Valuing New Goods for one approach to how new goods might be valued.

Adjusting the CPI for the improving quality poses similar difficulties. In many cases, the price of a specific consumer good will stay relatively constant from year to year, but more recent models of the good will be much better. For example, a good-quality laptop computer has had a price in the $500?$1,500 price range for many years. But this year's version is much more powerful than the models available, say, five or ten years ago. In effect, the price of a fixed-quality laptop has fallen dramatically, but this will not be apparent when the CPI shoppers are told to purchase a "new laptop." Statisticians who compute the CPI have grappled with this problem for many years and have come up with a variety of ingenious solutions (including the use of "hedonic price" models-see Application 1A.1: How Does Zillow.com Do It?). Still, many economists believe that the CPI continues to miss many improvements in goods' quality.

Outlet Bias

Finally, the fact that the Bureau of Labor Statistics sends buyers to the same retail outlets each month may overstate inflation. Actual consumers tend to seek out temporary sales or other bargains. They shop where they can make their money go the farthest. In recent years, this has meant shopping at giant discount stores such as Sam's Club or Costco rather than at traditional outlets. The CPI as currently constructed does not take such price-reducing strategies into account.

Consequences of the Biases

Measuring all these biases and devising a better CPI to take them into account is no easy task. Indeed, because the CPI is so widely used as "the" measure of inflation, any change can become a very hot political controversy. Still, there is general agreement that the current CPI may overstate actual increases in the cost of living by as much as 0:75 percent to 1:0 percent per year.1 By some estimates, correction of the index could reduce projected federal spending by as much as a half trillion dollars over a 10-year period. Hence, some politicians have proposed caps on COLAs in government programs. These suggestions have been very controversial, and none has so far been enacted. In private contracts, however, the upward biases in the CPI are frequently recognized. Few private COLAs provide full offsets to inflation as measured by the CPI.

There are many aspects of government policy where it is necessary to adjust for inflation. Some of these include (1) adjusting Social Security benefits, (2) changing cutoff points for income tax brackets, and (3) adjusting the values of "inflation-protected" bonds. How should the government choose a price index to make all of these adjustments? For example, many economists have suggested using a "chained" price index in which commodity bundles are changed every month to address substitution bias. According to some estimates this would reduce adjustments for inflation by about 0:25 percent per year. Would this be fair to elderly Social Security recipients who typically spend much more on (highly inflationary) medical care than do younger consumers?

Explanation

Although government should not use the s...

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255