Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Edition 12ISBN: 978-1133189022 Exercise 3

The Inefficiency of In-kind Programs

Most countries operate a wide variety of programs to help lowincome people. Some of these programs provide simple cash payments, but the most of these are "in-kind" programs that subsidize the prices of food, housing, or medical care. These types of programs have expanded greatly in recent years, while cash assistance has tended to lag. This sort of expansion, while perhaps made with noble intentions, has created two major problems in actually increasing the welfare of the lowincome populations served: (1) The programs do not provide nearly as much utility gain per dollar spent as cash programs; and (2) the cumulative effect of the programs may create a situation where low-income people have very little incentive to work. In this application, we look at both of these issues.

The Lump-Sum Principle, Again

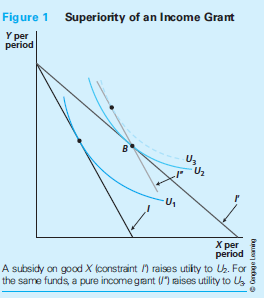

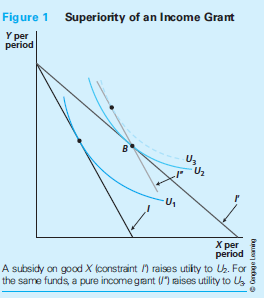

The inefficiency of in-kind programs is just a simple application of the lump-sum principle. In Figure 1, we show the budget constraint of a typical low-income person. A subsidy on good X (say food) would shift the budget constraint from I to I'. This would raise this person's utility from U 1 to U 2. The new

utility-maximizing point would be at B. An income grant that cost the same amount as the in-kind subsidy is shown by budget line I''. With this budget, this person could have achieved a utility level of U3. Because the in-kind program provides less utility than would an equally costly cash grant, the in-kind subsidy might be regarded as an inefficient way to provide assistance.

Studying the inefficiency of in-kind programs when there are many such programs available can be quite complicated. Because each program distorts consumption along one particular dimension (say, encouraging the purchase of more food), the effects on other subsidized items (say, housing) can actually reduce inefficiencies. In a 1994 study, Michael Murray studied such interactions among three major in-kind programs (those for food, housing, and medical care) in the United States.1 He concluded that the inefficiencies from multiple programs were somewhat less than those that would be estimated for each program individually. Still, in combination, all such programs yielded benefits to consumers that were worth (in terms of utility) only about 68 percent of what would have been provided by a simple cash grant costing the same.

The "Welfare Wall"

All welfare-type programs must reduce the benefits they provide as people's incomes rise. This effect creates an "implicit tax" on earning more. When there are multiple programs, each with its own implicit tax, these rates can accumulate to quite high levels. Some economists use the term "welfare wall" to refer to the barrier that such high rates create. For example, C. Eugene Steuerle finds that combined marginal tax rates can approach nearly 100 percent for single individuals in the United States who earn about $25,000 per year. 2 Although the precise effects on choices low-income people make about working are difficult to estimate, it would not be surprising if such effects were large.

Why is it so difficult to structure the formulas for in-kind benefits programs in ways that avoid the welfare wall?

Most countries operate a wide variety of programs to help lowincome people. Some of these programs provide simple cash payments, but the most of these are "in-kind" programs that subsidize the prices of food, housing, or medical care. These types of programs have expanded greatly in recent years, while cash assistance has tended to lag. This sort of expansion, while perhaps made with noble intentions, has created two major problems in actually increasing the welfare of the lowincome populations served: (1) The programs do not provide nearly as much utility gain per dollar spent as cash programs; and (2) the cumulative effect of the programs may create a situation where low-income people have very little incentive to work. In this application, we look at both of these issues.

The Lump-Sum Principle, Again

The inefficiency of in-kind programs is just a simple application of the lump-sum principle. In Figure 1, we show the budget constraint of a typical low-income person. A subsidy on good X (say food) would shift the budget constraint from I to I'. This would raise this person's utility from U 1 to U 2. The new

utility-maximizing point would be at B. An income grant that cost the same amount as the in-kind subsidy is shown by budget line I''. With this budget, this person could have achieved a utility level of U3. Because the in-kind program provides less utility than would an equally costly cash grant, the in-kind subsidy might be regarded as an inefficient way to provide assistance.

Studying the inefficiency of in-kind programs when there are many such programs available can be quite complicated. Because each program distorts consumption along one particular dimension (say, encouraging the purchase of more food), the effects on other subsidized items (say, housing) can actually reduce inefficiencies. In a 1994 study, Michael Murray studied such interactions among three major in-kind programs (those for food, housing, and medical care) in the United States.1 He concluded that the inefficiencies from multiple programs were somewhat less than those that would be estimated for each program individually. Still, in combination, all such programs yielded benefits to consumers that were worth (in terms of utility) only about 68 percent of what would have been provided by a simple cash grant costing the same.

The "Welfare Wall"

All welfare-type programs must reduce the benefits they provide as people's incomes rise. This effect creates an "implicit tax" on earning more. When there are multiple programs, each with its own implicit tax, these rates can accumulate to quite high levels. Some economists use the term "welfare wall" to refer to the barrier that such high rates create. For example, C. Eugene Steuerle finds that combined marginal tax rates can approach nearly 100 percent for single individuals in the United States who earn about $25,000 per year. 2 Although the precise effects on choices low-income people make about working are difficult to estimate, it would not be surprising if such effects were large.

Why is it so difficult to structure the formulas for in-kind benefits programs in ways that avoid the welfare wall?

Explanation

Welfare wall refers to the situation whe...

Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application 12th Edition by Walter Nicholson,Christopher Snyder

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255