Cengage Advantage Books: Foundations of the Legal Environment of Business 3rd Edition by Marianne Jennings

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1305117457

Cengage Advantage Books: Foundations of the Legal Environment of Business 3rd Edition by Marianne Jennings

Edition 3ISBN: 978-1305117457 Exercise 10

Escott v. BarChris Constr. Corp. 283 F. Supp. 643 (S.D.N.Y. 1968)

Bowling for Fraud: Right Up Our Alley

Facts

BarChris was a bowling alley company established in 1946. The bowling industry grew rapidly when automatic pin resetters went on the market in the mid-1950s. BarChris began a program of rapid expansion. BarChris used two methods of financing the construction of these alleys, both of which substantially drained the company's cash flow.

In 1960, BarChris's cash flow picture was troublesome, and it sold debentures. The debenture issue was registered with the SEC, approved, and sold. In spite of the cash boost from the sale, BarChris was still experiencing financial difficulties and declared bankruptcy in October 1962. The debenture holders were not paid their interest; BarChris defaulted.

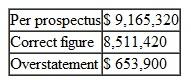

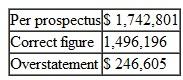

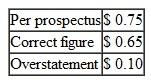

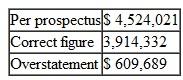

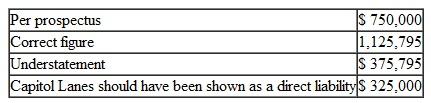

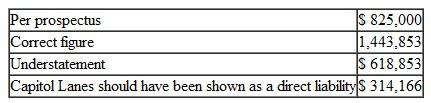

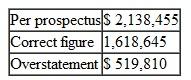

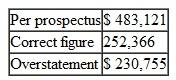

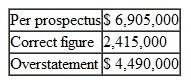

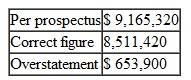

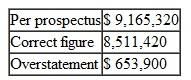

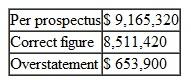

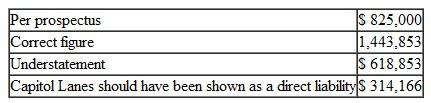

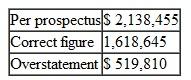

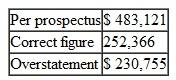

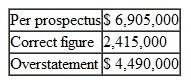

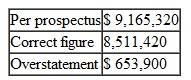

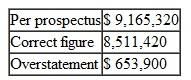

The purchasers of the BarChris debentures brought suit under Section 11 of the 1933 act. They claimed that the registration statement filed by BarChris contained false information and failed to disclose certain material information. The suit claimed that the audited financial statements prepared by a CPA firm were inaccurate and full of omissions. The following chart summarizes the problems with the financial statements submitted with the registration statements.

1. 1960 Earnings

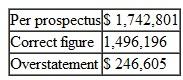

(a) Sales

(b) Net Operating Income

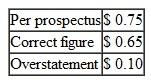

(c) Earnings per Share

2. 1960 Balance Sheet

Current Assets

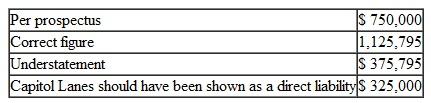

3. Contingent Liabilities as of December 31, 1960, on Alternative Method of Financing

4. Contingent Liabilities as of April 30, 1961

5. Earnings Figures for Quarter Ending March 31, 1961

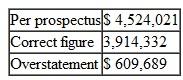

(a) Sales

(b) Gross Profit

6. Backlog as of March 31, 1961

7. Failure to Disclose Officers' Loans Outstanding and

0

0

8. Failure to Disclose Use of Proceeds in Manner Not

1

1

9. Failure to Disclose Customers' Delinquencies in May 1961 and BarChris's Potential Liability with Respect

2

2

The federal district court reviewed each of the defendants' conduct, including officers, directors, attorneys, and the auditors (Peat, Marwick, Mitchell Co.3).

Judicial Opinion

McLEAN, District Judge

Vitolo and Pugliese. They were the founders of the business who stuck with it to the end. Vitolo and Pugliese are each men of limited education. It is not hard to believe that for them the prospectus was difficult reading, if indeed they read it at all.

But whether it was or not is irrelevant. The liability of a director who signs a registration statement does not depend upon whether or not he read it or, if he did, whether or not he understood what he was reading. All in all, the position of Vitolo and Pugliese is not significantly different, for present purposes, from Russo's. They could not have believed that the registration statement was wholly true and that no material facts had been omitted. And in any case, there is nothing to show that they made any investigation of anything which they may not have known about or understood. They have not proved their due diligence defenses.

Kircher. Kircher was treasurer of BarChris and its chief financial officer. He is a certified public accountant and an intelligent man. He was thoroughly familiar with BarChris's financial affairs. He knew of the customers' delinquency problems. He knew how the financing proceeds were to be applied and he saw to it that they were so applied. He arranged the officers' loans and he knew all the facts concerning them.

Kircher has not proved his due diligence defenses.

Birnbaum. Birnbaum was a young lawyer, admitted to the bar in 1957, who, after brief periods of employment by two different law firms and an equally brief period of practicing in his own firm, was employed by BarChris as house counsel and assistant secretary in October 1960. Unfortunately for him, he became secretary and director of BarChris on April 17, 1961, after the first version of the registration statement had been filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. He signed the later amendments, thereby becoming responsible for the accuracy of the prospectus in its final form.

It seems probable that Birnbaum did not know of many of the inaccuracies in the prospectus. He must, however, have appreciated some of them. In any case, he made no investigation and relied on the others to get it right. Having failed to make such an investigation, he did not have reasonable ground to believe that all these statements were true. Birnbaum has not established his due diligence defenses except as to the audited 1960 exhibits.

Auslander. Auslander was an "outside" director, i.e., one who was not an officer of BarChris. Auslander was elected a director on April 17, 1961. The registration statement in its original form had already been filed, of course without his signature. On May 10, 1961, he signed a signature page for the first amendment to the registration statement which was filed on May 11, 1961. This was a separate sheet without any document attached. Auslander did not know that it was a signature page for a registration statement. He vaguely understood that it was something "for the SEC."

Auslander never saw a copy of the registration statement in its final form. It is true that Auslander became a director on the eve of the financing. He had little opportunity to familiarize himself with the company's affairs.

Section 11 imposes liability in the first instance upon a director, no matter how new he is.

Peat, Marwick. Peat, Marwick's work was in general charge of a member of the firm, Cummings, and more immediately in charge of Peat, Marwick's manager, Logan. Most of the actual work was performed by a senior accountant, Berardi, who had junior assistants, one of whom was Kennedy.

Berardi was then about thirty years old. He was not yet a CPA. He had had no previous experience with the bowling industry. This was his first job as a senior accountant. He could hardly have been given a more difficult assignment.

After obtaining a little background information on BarChris by talking to Logan and reviewing Peat, Marwick's work papers on its 1959 audit, Berardi examined the results of test checks of BarChris's accounting procedures which one of the junior accountants had made, and he prepared an "internal control questionnaire" and an "audit program." Thereafter, for a few days subsequent to December 30, 1960, he inspected BarChris's inventories and examined certain alley construction. Finally, on January 13, 1961, he began his auditing work which he carried on substantially continuously until it was completed on February 24, 1961. Toward the close of the work, Logan reviewed it and made various comments and suggestions to Berardi.

Accountants should not be held to a standard higher than that recognized in their profession. I do not do so here. Berardi's review did not come up to that standard. He did not take some of the steps which Peat, Marwick's written program prescribed. He did not spend an adequate amount of time on a task of this magnitude. Most important of all, he was too easily satisfied with glib answers to his inquiries.

This is not to say that he should have made a complete audit. But there were enough danger signals in the materials which he did examine to require some further investigation on his part. Generally accepted accounting standards required such further investigation under these circumstances. It is not always sufficient merely to ask questions.

Case Questions

1. How much time transpired between the sale of the debentures and BarChris's bankruptcy?

2. Were all of the errors and omissions material?

3. Make a list of the shortcomings of the defendants in their due diligence.

Bowling for Fraud: Right Up Our Alley

Facts

BarChris was a bowling alley company established in 1946. The bowling industry grew rapidly when automatic pin resetters went on the market in the mid-1950s. BarChris began a program of rapid expansion. BarChris used two methods of financing the construction of these alleys, both of which substantially drained the company's cash flow.

In 1960, BarChris's cash flow picture was troublesome, and it sold debentures. The debenture issue was registered with the SEC, approved, and sold. In spite of the cash boost from the sale, BarChris was still experiencing financial difficulties and declared bankruptcy in October 1962. The debenture holders were not paid their interest; BarChris defaulted.

The purchasers of the BarChris debentures brought suit under Section 11 of the 1933 act. They claimed that the registration statement filed by BarChris contained false information and failed to disclose certain material information. The suit claimed that the audited financial statements prepared by a CPA firm were inaccurate and full of omissions. The following chart summarizes the problems with the financial statements submitted with the registration statements.

1. 1960 Earnings

(a) Sales

(b) Net Operating Income

(c) Earnings per Share

2. 1960 Balance Sheet

Current Assets

3. Contingent Liabilities as of December 31, 1960, on Alternative Method of Financing

4. Contingent Liabilities as of April 30, 1961

5. Earnings Figures for Quarter Ending March 31, 1961

(a) Sales

(b) Gross Profit

6. Backlog as of March 31, 1961

7. Failure to Disclose Officers' Loans Outstanding and

0

08. Failure to Disclose Use of Proceeds in Manner Not

1

19. Failure to Disclose Customers' Delinquencies in May 1961 and BarChris's Potential Liability with Respect

2

2The federal district court reviewed each of the defendants' conduct, including officers, directors, attorneys, and the auditors (Peat, Marwick, Mitchell Co.3).

Judicial Opinion

McLEAN, District Judge

Vitolo and Pugliese. They were the founders of the business who stuck with it to the end. Vitolo and Pugliese are each men of limited education. It is not hard to believe that for them the prospectus was difficult reading, if indeed they read it at all.

But whether it was or not is irrelevant. The liability of a director who signs a registration statement does not depend upon whether or not he read it or, if he did, whether or not he understood what he was reading. All in all, the position of Vitolo and Pugliese is not significantly different, for present purposes, from Russo's. They could not have believed that the registration statement was wholly true and that no material facts had been omitted. And in any case, there is nothing to show that they made any investigation of anything which they may not have known about or understood. They have not proved their due diligence defenses.

Kircher. Kircher was treasurer of BarChris and its chief financial officer. He is a certified public accountant and an intelligent man. He was thoroughly familiar with BarChris's financial affairs. He knew of the customers' delinquency problems. He knew how the financing proceeds were to be applied and he saw to it that they were so applied. He arranged the officers' loans and he knew all the facts concerning them.

Kircher has not proved his due diligence defenses.

Birnbaum. Birnbaum was a young lawyer, admitted to the bar in 1957, who, after brief periods of employment by two different law firms and an equally brief period of practicing in his own firm, was employed by BarChris as house counsel and assistant secretary in October 1960. Unfortunately for him, he became secretary and director of BarChris on April 17, 1961, after the first version of the registration statement had been filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. He signed the later amendments, thereby becoming responsible for the accuracy of the prospectus in its final form.

It seems probable that Birnbaum did not know of many of the inaccuracies in the prospectus. He must, however, have appreciated some of them. In any case, he made no investigation and relied on the others to get it right. Having failed to make such an investigation, he did not have reasonable ground to believe that all these statements were true. Birnbaum has not established his due diligence defenses except as to the audited 1960 exhibits.

Auslander. Auslander was an "outside" director, i.e., one who was not an officer of BarChris. Auslander was elected a director on April 17, 1961. The registration statement in its original form had already been filed, of course without his signature. On May 10, 1961, he signed a signature page for the first amendment to the registration statement which was filed on May 11, 1961. This was a separate sheet without any document attached. Auslander did not know that it was a signature page for a registration statement. He vaguely understood that it was something "for the SEC."

Auslander never saw a copy of the registration statement in its final form. It is true that Auslander became a director on the eve of the financing. He had little opportunity to familiarize himself with the company's affairs.

Section 11 imposes liability in the first instance upon a director, no matter how new he is.

Peat, Marwick. Peat, Marwick's work was in general charge of a member of the firm, Cummings, and more immediately in charge of Peat, Marwick's manager, Logan. Most of the actual work was performed by a senior accountant, Berardi, who had junior assistants, one of whom was Kennedy.

Berardi was then about thirty years old. He was not yet a CPA. He had had no previous experience with the bowling industry. This was his first job as a senior accountant. He could hardly have been given a more difficult assignment.

After obtaining a little background information on BarChris by talking to Logan and reviewing Peat, Marwick's work papers on its 1959 audit, Berardi examined the results of test checks of BarChris's accounting procedures which one of the junior accountants had made, and he prepared an "internal control questionnaire" and an "audit program." Thereafter, for a few days subsequent to December 30, 1960, he inspected BarChris's inventories and examined certain alley construction. Finally, on January 13, 1961, he began his auditing work which he carried on substantially continuously until it was completed on February 24, 1961. Toward the close of the work, Logan reviewed it and made various comments and suggestions to Berardi.

Accountants should not be held to a standard higher than that recognized in their profession. I do not do so here. Berardi's review did not come up to that standard. He did not take some of the steps which Peat, Marwick's written program prescribed. He did not spend an adequate amount of time on a task of this magnitude. Most important of all, he was too easily satisfied with glib answers to his inquiries.

This is not to say that he should have made a complete audit. But there were enough danger signals in the materials which he did examine to require some further investigation on his part. Generally accepted accounting standards required such further investigation under these circumstances. It is not always sufficient merely to ask questions.

Case Questions

1. How much time transpired between the sale of the debentures and BarChris's bankruptcy?

2. Were all of the errors and omissions material?

3. Make a list of the shortcomings of the defendants in their due diligence.

Explanation

Brief History of the case:

The case is ...

Cengage Advantage Books: Foundations of the Legal Environment of Business 3rd Edition by Marianne Jennings

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255