Economics for Today 9th Edition by Irvin Tucker

Edition 9ISBN: 978-1305507111

Economics for Today 9th Edition by Irvin Tucker

Edition 9ISBN: 978-1305507111 Exercise 41

WHY IS WATER LESS EXPENSIVE THAN DIAMONDS?

Applicable Concepts: total utility and marginal utility

Adam Smith posed a paradox in The Wealth of Nations. Water is essential to life and therefore should be of great value. On the other hand, diamonds are not essential to life, so people should value them less than water. Yet, even though water provides more utility, it is cheaper than diamonds. Smith's puzzle came to be known as the diamond-water paradox. Now you can use marginal utility analysis to explain something that baffled the father of economics.

Early economists failed to find the key to the diamond-water puzzle because they did not distinguish between marginal and total utility. Marginal utility theory was not developed until the late nineteenth century. Water is life-giving and does indeed yield much higher total utility than diamonds. However, marginal utility, and not total utility, determines the price. Water is plentiful in most of the world, so its marginal utility is low. This follows the law of diminishing marginal utility.

Jewelry-quality diamonds, on the other hand, are scarce. Because we have relatively few diamonds, the quantity of diamonds consumed is not large. As a result, the marginal utility of diamonds and the price buyers are willing to pay for them are quite high. Thus, scarcity raises marginal utility and price regardless of the size of total utility.

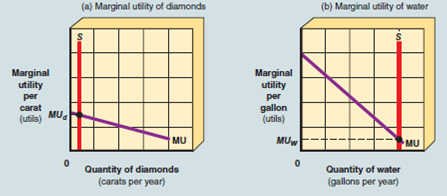

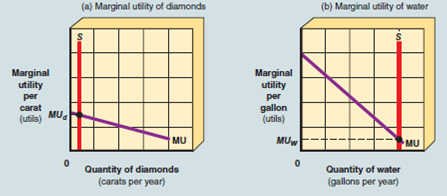

EXHIBIT 2 The Diamond-Water Paradox

Exhibit 2 presents a graphical analysis that you can use to unravel the alleged paradox. Part (a) shows the marginal utility per carat you receive from each diamond consumed, and part (b) represents marginal utility per gallon of water consumed. The vertical line, S , in each graph is the supply of water or diamonds available per year. Since water is much more plentiful than diamonds, the supply curve for water intersects the marginal utility curve at MU w , which is close to zero. Conversely, the supply curve for diamonds intersects the marginal utility curve at a much higher marginal utility, MU d. Because of the relative marginal utilities of water and diamonds, you are willing to pay much more for one more carat of a diamond than for one more gallon of water.

Suppose the price per gallon of water is 1 cent and the price per carat of a diamond is $10,000. Is the total utility of diamonds 10,000 times as great as the total utility received from water?

Applicable Concepts: total utility and marginal utility

Adam Smith posed a paradox in The Wealth of Nations. Water is essential to life and therefore should be of great value. On the other hand, diamonds are not essential to life, so people should value them less than water. Yet, even though water provides more utility, it is cheaper than diamonds. Smith's puzzle came to be known as the diamond-water paradox. Now you can use marginal utility analysis to explain something that baffled the father of economics.

Early economists failed to find the key to the diamond-water puzzle because they did not distinguish between marginal and total utility. Marginal utility theory was not developed until the late nineteenth century. Water is life-giving and does indeed yield much higher total utility than diamonds. However, marginal utility, and not total utility, determines the price. Water is plentiful in most of the world, so its marginal utility is low. This follows the law of diminishing marginal utility.

Jewelry-quality diamonds, on the other hand, are scarce. Because we have relatively few diamonds, the quantity of diamonds consumed is not large. As a result, the marginal utility of diamonds and the price buyers are willing to pay for them are quite high. Thus, scarcity raises marginal utility and price regardless of the size of total utility.

EXHIBIT 2 The Diamond-Water Paradox

Exhibit 2 presents a graphical analysis that you can use to unravel the alleged paradox. Part (a) shows the marginal utility per carat you receive from each diamond consumed, and part (b) represents marginal utility per gallon of water consumed. The vertical line, S , in each graph is the supply of water or diamonds available per year. Since water is much more plentiful than diamonds, the supply curve for water intersects the marginal utility curve at MU w , which is close to zero. Conversely, the supply curve for diamonds intersects the marginal utility curve at a much higher marginal utility, MU d. Because of the relative marginal utilities of water and diamonds, you are willing to pay much more for one more carat of a diamond than for one more gallon of water.

Suppose the price per gallon of water is 1 cent and the price per carat of a diamond is $10,000. Is the total utility of diamonds 10,000 times as great as the total utility received from water?

Explanation

Diamonds are scarce and water ...

Economics for Today 9th Edition by Irvin Tucker

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255