Global Business 4th Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 4ISBN: 978-1305500891

Global Business 4th Edition by Mike Peng

Edition 4ISBN: 978-1305500891 Exercise 5

EMERGING MARKETS: Monetizing the Maasai Tribal Name

Living in Kenya and Tanzania, the Maasai with their recognizable red attire represent one of the most iconic tribes in Africa. As (semi-)nomadic pastoralists, the Maasai have been raising cattle and hunting with some small-scale agriculture near Africa's finest game parks, such as Serengeti, for ages. Known as fierce warriors, the Maasai have won the respect of rival tribes, colonial authorities, and modern governments of Kenya and Tanzania. Together with lions, giraffes, and zebras, a Maasai village is among the "must-see" places for a typical African safari trip.

For those of you who cannot travel so far to visit Africa, you can still get a piece of the colorful Maasai culture. Jaguar Land Rover marketed a limited-edition version of its Freelander 4 x 4 named Maasai. Louis Vuitton developed a line of menswear and womenswear fashion inspired by the Maasai dress. Diane von Furstenberg hawked a red pillow and cushion line simply called Maasai. The Switzerland-based Maasai Barefoot Technology (MBT) developed a line of roundbottom shoes to simulate the challenge of Maasai walking barefoot on soft earth. An Italian penmaker, Delta, named its high-end red-capped fountain pen Maasai. A single pen retails at US$600, "which is like three or four good cows," according to a Maasai tribesman. These are just high-profile examples. Experts estimate that perhaps 10,000 firms around the world use the Maasai name, selling everything from hats to legal services.

All this sounds fascinating, except one catch. While these firms made millions, neither a single Maasai individual nor the tribe has ever received a penny. This is where a huge ethical and legal debate has erupted. Legally, the Maasai case is weak. The tribe has never made any formal effort to enforce any intellectual property rights (IPR) of its culture and identity. With approximately two million tribe members spread between Kenya and Tanzania, just who can officially represent the Maasai is up in the air. An expert laughed at this idea, by saying, "Look, if it could work, the French budget deficit would be gone by demanding royalties on French fries."

However, from an ethical standpoint, all the firms named above claim to be interested in corporate social responsibility (CSR). If they indeed are interested in the high road to business ethics, expropriating-or, if you may, "ripping off" or "stealing"-the Maasai name without compensation has obviously become a huge embarrassment.

Although steeped in tradition, the Maasai are also constantly in touch with the modern world. Their frequent interactions with tourists have made them aware how much value there is in the Maasai name. But they are frustrated by their lack of knowledge about the rules of the game concerning IPR. Fortunately, they have been helped by Ron Layton, a New Zealander who is a former diplomat and now runs a nonprofit Light Years IP advising groups in the developing world such as the Maasai. Layton previously helped the Ethiopian government wage a legal battle with Starbucks, which marketed Harrar, Sidamo, and Yirgacheffe coffee lines from different regions of Ethiopia without compensation. Although Starbucks projects an image of being very serious about CSR, it initially fought these efforts but eventually agreed to recognize Ethiopia's claims.

Emboldened by the success in fighting Starbucks, Layton worked with Maasai elders such as Issac oleTialolo to establish a nonprofit registered in Tanzania called Maasai Intellectual Property Initiative (MIPI). They crafted MIPI bylaws that would reflect traditional Maasai cultural values and that would satisfy the requirements of Western courts-in preparation for an eventual legal showdown. Layton himself made no money from MIPI, and his only income was the salary from his own nonprofit Light Years IP A US$1.25 million grant from the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) helped to defray some of the expenses. The challenge now is to have more tribal leaders and elders to sign up with MIPI so that MIPI would be viewed both externally and internally as the legitimate representative of the Maasai tribe. How the tribe can monetize its name remains to be seen in the future.

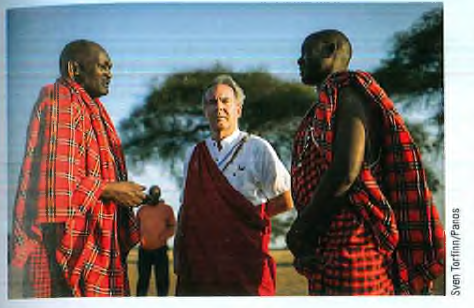

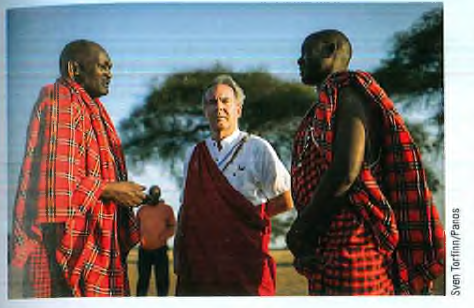

(left to right) Isaac ole Tiabolo, Ron Layton, and a staff member with MIPI

Source: Bloomberg Businessweek, 2013, M3asai'M, October 24: 88.

ON ETHICS: Assuming you can afford (and are interested in) some of the "Maasai" products, would you like to pay more for these products if royalties are paid to the Maasai

Living in Kenya and Tanzania, the Maasai with their recognizable red attire represent one of the most iconic tribes in Africa. As (semi-)nomadic pastoralists, the Maasai have been raising cattle and hunting with some small-scale agriculture near Africa's finest game parks, such as Serengeti, for ages. Known as fierce warriors, the Maasai have won the respect of rival tribes, colonial authorities, and modern governments of Kenya and Tanzania. Together with lions, giraffes, and zebras, a Maasai village is among the "must-see" places for a typical African safari trip.

For those of you who cannot travel so far to visit Africa, you can still get a piece of the colorful Maasai culture. Jaguar Land Rover marketed a limited-edition version of its Freelander 4 x 4 named Maasai. Louis Vuitton developed a line of menswear and womenswear fashion inspired by the Maasai dress. Diane von Furstenberg hawked a red pillow and cushion line simply called Maasai. The Switzerland-based Maasai Barefoot Technology (MBT) developed a line of roundbottom shoes to simulate the challenge of Maasai walking barefoot on soft earth. An Italian penmaker, Delta, named its high-end red-capped fountain pen Maasai. A single pen retails at US$600, "which is like three or four good cows," according to a Maasai tribesman. These are just high-profile examples. Experts estimate that perhaps 10,000 firms around the world use the Maasai name, selling everything from hats to legal services.

All this sounds fascinating, except one catch. While these firms made millions, neither a single Maasai individual nor the tribe has ever received a penny. This is where a huge ethical and legal debate has erupted. Legally, the Maasai case is weak. The tribe has never made any formal effort to enforce any intellectual property rights (IPR) of its culture and identity. With approximately two million tribe members spread between Kenya and Tanzania, just who can officially represent the Maasai is up in the air. An expert laughed at this idea, by saying, "Look, if it could work, the French budget deficit would be gone by demanding royalties on French fries."

However, from an ethical standpoint, all the firms named above claim to be interested in corporate social responsibility (CSR). If they indeed are interested in the high road to business ethics, expropriating-or, if you may, "ripping off" or "stealing"-the Maasai name without compensation has obviously become a huge embarrassment.

Although steeped in tradition, the Maasai are also constantly in touch with the modern world. Their frequent interactions with tourists have made them aware how much value there is in the Maasai name. But they are frustrated by their lack of knowledge about the rules of the game concerning IPR. Fortunately, they have been helped by Ron Layton, a New Zealander who is a former diplomat and now runs a nonprofit Light Years IP advising groups in the developing world such as the Maasai. Layton previously helped the Ethiopian government wage a legal battle with Starbucks, which marketed Harrar, Sidamo, and Yirgacheffe coffee lines from different regions of Ethiopia without compensation. Although Starbucks projects an image of being very serious about CSR, it initially fought these efforts but eventually agreed to recognize Ethiopia's claims.

Emboldened by the success in fighting Starbucks, Layton worked with Maasai elders such as Issac oleTialolo to establish a nonprofit registered in Tanzania called Maasai Intellectual Property Initiative (MIPI). They crafted MIPI bylaws that would reflect traditional Maasai cultural values and that would satisfy the requirements of Western courts-in preparation for an eventual legal showdown. Layton himself made no money from MIPI, and his only income was the salary from his own nonprofit Light Years IP A US$1.25 million grant from the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) helped to defray some of the expenses. The challenge now is to have more tribal leaders and elders to sign up with MIPI so that MIPI would be viewed both externally and internally as the legitimate representative of the Maasai tribe. How the tribe can monetize its name remains to be seen in the future.

(left to right) Isaac ole Tiabolo, Ron Layton, and a staff member with MIPI

Source: Bloomberg Businessweek, 2013, M3asai'M, October 24: 88.

ON ETHICS: Assuming you can afford (and are interested in) some of the "Maasai" products, would you like to pay more for these products if royalties are paid to the Maasai

Explanation

It is ethical practice to provide the ro...

Global Business 4th Edition by Mike Peng

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255