Corporate Communication 6th Edition by Paul Argenti

Edition 6ISBN: 978-0073403175

Corporate Communication 6th Edition by Paul Argenti

Edition 6ISBN: 978-0073403175 Exercise 1

Westwood Publishing

Dan Cassidy, a 2008 graduate of the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College, was driving home from work listening to more depressing news on the radio about layoffs at another large media company. He had just left a meeting with his boss, Catherine Callahan (See Exhibit 7.1), the Vice President of Human Resources at Westwood Publishing. "Dan, we are going to have to let some of the old-timers go," she said. "I'm hoping that the CEO will buy my plan for a voluntary severance and early retirement package. We should be able to move out some of the deadwood in this company as well."

Westwood Publishing had never laid off anyone in the 16 years of its existence. As the Director of Employee Relations, Dan would be responsible for telling employees about the new policy within the next couple of days.

As he looked at the beautiful southern California hills surrounding the freeway, many thoughts were going through his head. How should he identify the issues involved for all employees? Should he get the people in corporate communication involved? Who would be the best person to release the information? What about communication with other Westwood constituencies? And what would be the long-term effects of what would be reported in the media as a "major downsizing"?

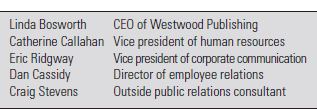

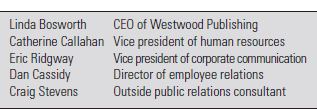

EXHIBIT 7.1 THE PEOPLE IN THE CASE

WESTWOOD PUBLISHING BACKGROUND

Westwood was started by Linda Bosworth, a brilliant UCLA graduate, following her graduation from college in 1995. With only $10,000 in capital borrowed from her father, Bosworth had built the firm up to a multimillion-dollar trade magazine publisher with hundreds of titles and a broad subscriber base. Beginning in the mid-1990s, Westwood began to focus strategically on high-tech trade publications.

As the business grew, Bosworth gradually turned the day-to-day operation of Westwood over to professional managers, preferring young MBAs from top business schools. But the original group of employees, mostly men in their mid-50s, still represented the bulk of senior management at Westwood.

By the turn of the century, analysts had predicted that the publishing industry in general, and Westwood in particular, was ready for consolidation. Many of Westwood's competitors had trimmed their workforces repeatedly after the dot-com bubble burst in early 2000. By this point, half of Westwood's titles were for high-tech and Internet companies. But Bosworth felt that keeping all of her employees happy through good times and bad was more important than anything else.

As other business-to-business publishing companies underwent merger and acquisition (M A) deals-and trade magazine publishers with solid online media divisions continued to sell themselves to media conglomerates at a tidy profit-Westwood resisted making any deals, instead standing its ground, avoiding the messy consolidation of print titles, and having to deal with potential redundancies in departments such as circulation and office support personnel.

Even though one-third of the American newspaper jobs that existed when Bosworth launched her company in 1995 had already disappeared by 2011, in a speech that Bosworth delivered to all of Westwood's employees that same year, she outlined the company's philosophy toward employee turnover: "You, the employees of Westwood, are the most important asset that we have. Despite the difficult times this company now faces, you have my assurance that I will never ask any of you to leave for economic reasons. This is not General Motors!"

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION AT WESTWOOD

The company relied on a small staff of communication professionals to handle its communication efforts. All of the various activities that could be decentralized (e.g., internal communications, investor relations) were housed in the appropriate functional areas. This organization developed naturally as the company grew to become one of the largest independent trade magazine publishers in the United States.

The main outreaches to employees were annual town hall meetings in the major cities where Westwood had offices, where slide-heavy presentations from Bosworth and other top company executives would draw upwards of 300 employees. Ironically, for a publishing company, Westwood's Intranet was updated infrequently, and the company's communications team relied mostly on desk drops of formal memos and newsletters to get messages out to its workers.

Bosworth, as a young owner and CEO, enjoyed much attention from the press as a result of her meteoric rise in the business world. She relied on an outside consultant, Craig Stevens, to handle her own public relations. Stevens also had a tremendous amount of influence over the communications department at the company itself.

The VP of Corporate Communication, Eric Ridgway, was actually one of the several employees who would be affected by the current plan to trim the workforce. He had been hired early on as a favor to Bosworth's father. Ridgway had spent 25 years at the Los Angeles Times before signing on at Westwood, and although he had a media background, he did not know much about the trade magazine business or the industries that made up Westwood's primary subscriber base. The problems associated with Ridgway made the communications effort more difficult for both Dan Cassidy and the outside counsel advising him through the process.

THE VOLUNTARY SEVERANCE AND EARLY RETIREMENT PROGRAM

Although the CEO was very much against the two programs that were about to be implemented, she had been convinced by both Callahan, the Head of Human Resources, and her Board of Directors that something had to be done immediately, or the company itself would be at risk.

The way the programs would work, several senior managers would be told about the generous voluntary severance or early retirement packages and asked to avail themselves of the appropriate plan. Thus, a Director who had received less than excellent performance appraisals for two consecutive years would be a prime candidate for voluntary severance, whereas a Vice President approaching 60 would be offered the retirement package. Although both of these programs were "voluntary," the supervisors responsible for identifying candidates were urged to get the weaker people to agree as soon as possible.

COMMUNICATING ABOUT THE PLANS

Cassidy reported to work the following day and was asked to attend a meeting with his supervisor, Catherine Callahan, Bosworth, and Craig Stevens. "Well, Dan, how are you going to pull this one off?" joked Bosworth. Cassidy responded, "Quite honestly, Linda, given your position on this issue, my feeling is that you need to get involved with the announcement tomorrow."

As the discussion progressed, however, it was obvious to Dan Cassidy that he was the one that his boss and the head of the company wanted to take the heat. After two hours, Bosworth looked Dan squarely in the eye and said: "This was not my idea in the first place, but I know we have no choice but to adopt the voluntary severance packages and early retirement plans for Westwood Publishing. Unfortunately, I need to leave for a conference in New York the day after tomorrow. You and Catherine are going to have to take responsibility this time."

Dan looked over at Catherine. She was gazing at a drawing on Bosworth's wall. It was a picture of someone about to lose his head by guillotine during the French revolution. Somehow the picture seemed very appropriate to their situation.

What advice would you give Cassidy about how communications to employees are structured at Westwood?

Dan Cassidy, a 2008 graduate of the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College, was driving home from work listening to more depressing news on the radio about layoffs at another large media company. He had just left a meeting with his boss, Catherine Callahan (See Exhibit 7.1), the Vice President of Human Resources at Westwood Publishing. "Dan, we are going to have to let some of the old-timers go," she said. "I'm hoping that the CEO will buy my plan for a voluntary severance and early retirement package. We should be able to move out some of the deadwood in this company as well."

Westwood Publishing had never laid off anyone in the 16 years of its existence. As the Director of Employee Relations, Dan would be responsible for telling employees about the new policy within the next couple of days.

As he looked at the beautiful southern California hills surrounding the freeway, many thoughts were going through his head. How should he identify the issues involved for all employees? Should he get the people in corporate communication involved? Who would be the best person to release the information? What about communication with other Westwood constituencies? And what would be the long-term effects of what would be reported in the media as a "major downsizing"?

EXHIBIT 7.1 THE PEOPLE IN THE CASE

WESTWOOD PUBLISHING BACKGROUND

Westwood was started by Linda Bosworth, a brilliant UCLA graduate, following her graduation from college in 1995. With only $10,000 in capital borrowed from her father, Bosworth had built the firm up to a multimillion-dollar trade magazine publisher with hundreds of titles and a broad subscriber base. Beginning in the mid-1990s, Westwood began to focus strategically on high-tech trade publications.

As the business grew, Bosworth gradually turned the day-to-day operation of Westwood over to professional managers, preferring young MBAs from top business schools. But the original group of employees, mostly men in their mid-50s, still represented the bulk of senior management at Westwood.

By the turn of the century, analysts had predicted that the publishing industry in general, and Westwood in particular, was ready for consolidation. Many of Westwood's competitors had trimmed their workforces repeatedly after the dot-com bubble burst in early 2000. By this point, half of Westwood's titles were for high-tech and Internet companies. But Bosworth felt that keeping all of her employees happy through good times and bad was more important than anything else.

As other business-to-business publishing companies underwent merger and acquisition (M A) deals-and trade magazine publishers with solid online media divisions continued to sell themselves to media conglomerates at a tidy profit-Westwood resisted making any deals, instead standing its ground, avoiding the messy consolidation of print titles, and having to deal with potential redundancies in departments such as circulation and office support personnel.

Even though one-third of the American newspaper jobs that existed when Bosworth launched her company in 1995 had already disappeared by 2011, in a speech that Bosworth delivered to all of Westwood's employees that same year, she outlined the company's philosophy toward employee turnover: "You, the employees of Westwood, are the most important asset that we have. Despite the difficult times this company now faces, you have my assurance that I will never ask any of you to leave for economic reasons. This is not General Motors!"

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION AT WESTWOOD

The company relied on a small staff of communication professionals to handle its communication efforts. All of the various activities that could be decentralized (e.g., internal communications, investor relations) were housed in the appropriate functional areas. This organization developed naturally as the company grew to become one of the largest independent trade magazine publishers in the United States.

The main outreaches to employees were annual town hall meetings in the major cities where Westwood had offices, where slide-heavy presentations from Bosworth and other top company executives would draw upwards of 300 employees. Ironically, for a publishing company, Westwood's Intranet was updated infrequently, and the company's communications team relied mostly on desk drops of formal memos and newsletters to get messages out to its workers.

Bosworth, as a young owner and CEO, enjoyed much attention from the press as a result of her meteoric rise in the business world. She relied on an outside consultant, Craig Stevens, to handle her own public relations. Stevens also had a tremendous amount of influence over the communications department at the company itself.

The VP of Corporate Communication, Eric Ridgway, was actually one of the several employees who would be affected by the current plan to trim the workforce. He had been hired early on as a favor to Bosworth's father. Ridgway had spent 25 years at the Los Angeles Times before signing on at Westwood, and although he had a media background, he did not know much about the trade magazine business or the industries that made up Westwood's primary subscriber base. The problems associated with Ridgway made the communications effort more difficult for both Dan Cassidy and the outside counsel advising him through the process.

THE VOLUNTARY SEVERANCE AND EARLY RETIREMENT PROGRAM

Although the CEO was very much against the two programs that were about to be implemented, she had been convinced by both Callahan, the Head of Human Resources, and her Board of Directors that something had to be done immediately, or the company itself would be at risk.

The way the programs would work, several senior managers would be told about the generous voluntary severance or early retirement packages and asked to avail themselves of the appropriate plan. Thus, a Director who had received less than excellent performance appraisals for two consecutive years would be a prime candidate for voluntary severance, whereas a Vice President approaching 60 would be offered the retirement package. Although both of these programs were "voluntary," the supervisors responsible for identifying candidates were urged to get the weaker people to agree as soon as possible.

COMMUNICATING ABOUT THE PLANS

Cassidy reported to work the following day and was asked to attend a meeting with his supervisor, Catherine Callahan, Bosworth, and Craig Stevens. "Well, Dan, how are you going to pull this one off?" joked Bosworth. Cassidy responded, "Quite honestly, Linda, given your position on this issue, my feeling is that you need to get involved with the announcement tomorrow."

As the discussion progressed, however, it was obvious to Dan Cassidy that he was the one that his boss and the head of the company wanted to take the heat. After two hours, Bosworth looked Dan squarely in the eye and said: "This was not my idea in the first place, but I know we have no choice but to adopt the voluntary severance packages and early retirement plans for Westwood Publishing. Unfortunately, I need to leave for a conference in New York the day after tomorrow. You and Catherine are going to have to take responsibility this time."

Dan looked over at Catherine. She was gazing at a drawing on Bosworth's wall. It was a picture of someone about to lose his head by guillotine during the French revolution. Somehow the picture seemed very appropriate to their situation.

What advice would you give Cassidy about how communications to employees are structured at Westwood?

Explanation

WW publishing which is owned by Ms. LB h...

Corporate Communication 6th Edition by Paul Argenti

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255