Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Edition 7ISBN: 978-0077837280

Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Edition 7ISBN: 978-0077837280 Exercise 5

Field experiments have played a key role in the assessment of the importance of competitive interactions in nature. Joseph Connell (1974) and Nelson Hairston, Sr. (1989), two of the pioneers in the use of field experiments in ecology, outlined their proper design and execution. Connell points out that one of the most substantial differences between laboratory and field experiments is that in the laboratory setting, the investigator controls all important factors but one, the factor of interest. In contrast, in field experiments, all factors are allowed to vary naturally (the investigator generally has no choice) while the factor of interest is controlled, or manipulated, by the investigator.

Both laboratory and field experiments have played an important role in ecology, but it is the field experiment that provides the key to unlock the secrets of complex interactions in nature. Why is it that field experiments are more useful in this regard Connell pointed out that compared to laboratory experiments, the results of field experiments can be more directly applied to understanding relationships in nature because "interactions with other organisms, and the natural variation in the abiotic environment, are included in the experiment." The best field experiments are those that are executed with the least disturbance to the natural community. The utility of field experiments, however, depends upon several design features.

Knowledge of Initial Conditions

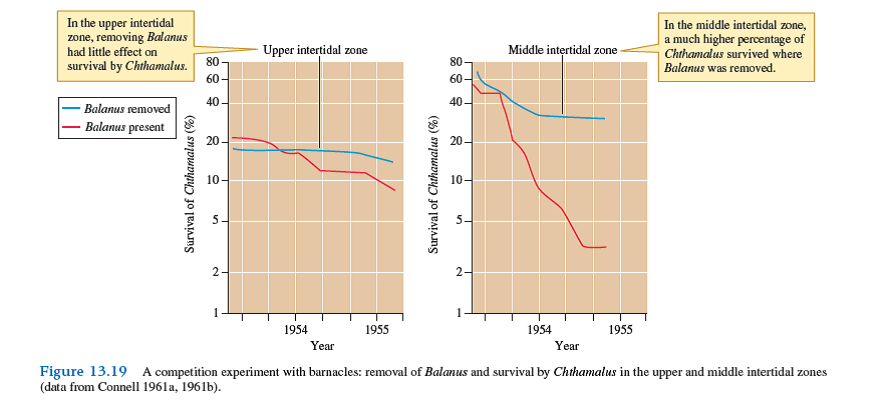

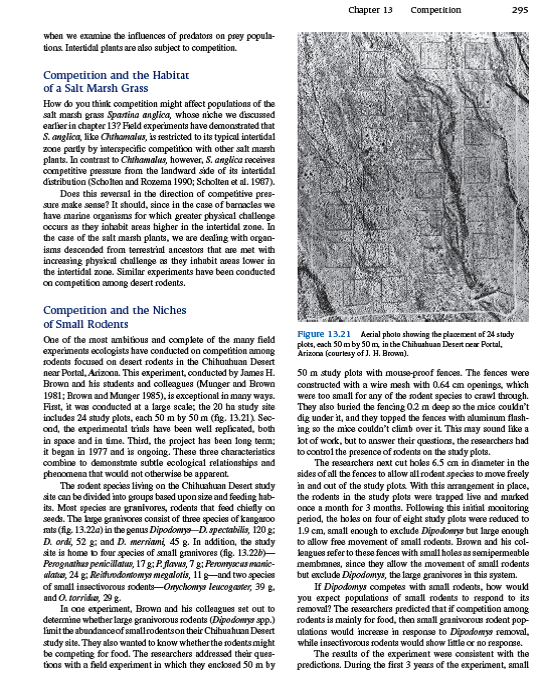

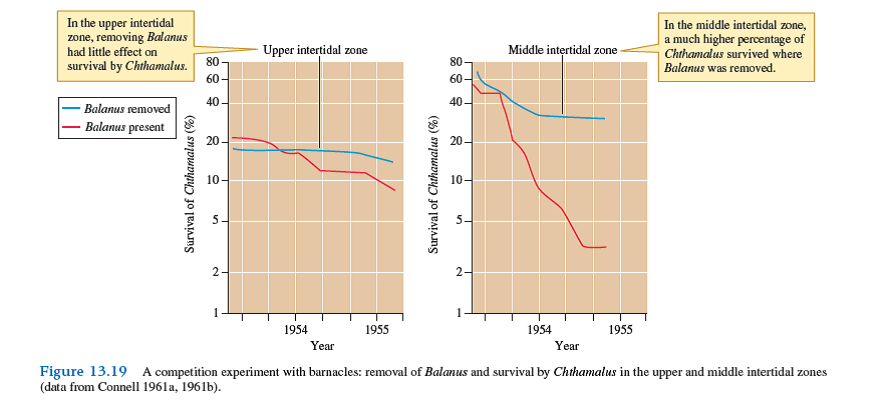

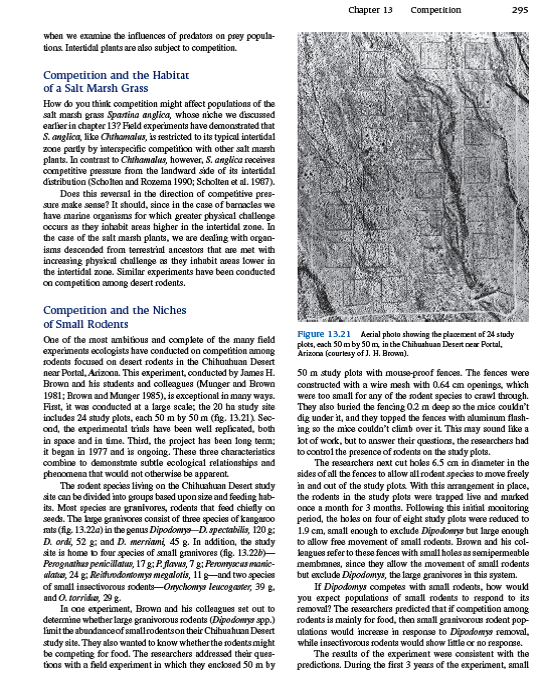

To test for change in response to experimental manipulation, you have to know what conditions were like before the manipulation. Departures from initial conditions indicate a response to the experimental treatments. For instance, in his experiments on competition between barnacles, Connell first estimated the initial population density of one of the species in all his study plots (see fig. 13.19 ). Brown and his colleagues (Brown and Munger 1985; Heske, Brown, and Mistry 1994) were also careful to measure the population densities of all rodent species in their study plots several times before excluding large granivorous rodents from their experimental plots.

Controls

As in laboratory experiments, field experiments must include controls. Without controls it would be impossible to determine whether or not an experimental treatment has had an effect. Tansley (1917) created controls for his experiments on competition by growing each of his potential competitors by themselves in acidic and basic soils. What was the control for the experiment on competition among desert rodents Brown's research team created controls by surrounding study plots with their mouse-proof fence but then cutting holes 6.5 cm in diameter in the fences to allow large granivorous rodents to move freely into and out of the plots.

Replication

Field experiments, where possible, should include replication. Why Ecological systems and environmental conditions are variable, both in time and space. Replication is intended to capture this variation. The question posed by the experimenter is whether an experimental effect is apparent despite variation. Ecologists use statistics to make such a judgment. Without replication, you would never know if the results could be repeated either in time or space.

What is considered acceptable study design has changed over the decades, reflecting increasing familiarity and concern for statistical analysis. In Tansley's experiments on how competition may restrict the distribution of Galium species to particular soils, replication was totally lacking. In Tansley's experiment, each condition (soil type) was represented just one time. Connell's later experiments with barnacles included some replication, but it was still limited at each tidal level. However, since there was a great deal of consistency in response across tidal levels, we can accept that competition acts as a significant force limiting barnacle distributions within the intertidal zone. In contrast to these earlier experiments, the more recent experiments by Brown on competition among desert rodents were replicated sufficiently for statistical analysis and repeated a second time.

The reviews by Connell and Hairston provide a guide to field experimentation as it has been conducted in the past few decades. However, as we shall see in section VI, the need for experimentation at large scales is forcing ecologists to further expand their concept of experimental design.

Why did Brown's research team (see p. 295) create controls by completely fencing study plots and then cutting holes in their sides to allow free passage of rodents into and out of the plot Why not just compare the density of small rodents in the large granivore removal plots with their densities in the surrounding desert

Both laboratory and field experiments have played an important role in ecology, but it is the field experiment that provides the key to unlock the secrets of complex interactions in nature. Why is it that field experiments are more useful in this regard Connell pointed out that compared to laboratory experiments, the results of field experiments can be more directly applied to understanding relationships in nature because "interactions with other organisms, and the natural variation in the abiotic environment, are included in the experiment." The best field experiments are those that are executed with the least disturbance to the natural community. The utility of field experiments, however, depends upon several design features.

Knowledge of Initial Conditions

To test for change in response to experimental manipulation, you have to know what conditions were like before the manipulation. Departures from initial conditions indicate a response to the experimental treatments. For instance, in his experiments on competition between barnacles, Connell first estimated the initial population density of one of the species in all his study plots (see fig. 13.19 ). Brown and his colleagues (Brown and Munger 1985; Heske, Brown, and Mistry 1994) were also careful to measure the population densities of all rodent species in their study plots several times before excluding large granivorous rodents from their experimental plots.

Controls

As in laboratory experiments, field experiments must include controls. Without controls it would be impossible to determine whether or not an experimental treatment has had an effect. Tansley (1917) created controls for his experiments on competition by growing each of his potential competitors by themselves in acidic and basic soils. What was the control for the experiment on competition among desert rodents Brown's research team created controls by surrounding study plots with their mouse-proof fence but then cutting holes 6.5 cm in diameter in the fences to allow large granivorous rodents to move freely into and out of the plots.

Replication

Field experiments, where possible, should include replication. Why Ecological systems and environmental conditions are variable, both in time and space. Replication is intended to capture this variation. The question posed by the experimenter is whether an experimental effect is apparent despite variation. Ecologists use statistics to make such a judgment. Without replication, you would never know if the results could be repeated either in time or space.

What is considered acceptable study design has changed over the decades, reflecting increasing familiarity and concern for statistical analysis. In Tansley's experiments on how competition may restrict the distribution of Galium species to particular soils, replication was totally lacking. In Tansley's experiment, each condition (soil type) was represented just one time. Connell's later experiments with barnacles included some replication, but it was still limited at each tidal level. However, since there was a great deal of consistency in response across tidal levels, we can accept that competition acts as a significant force limiting barnacle distributions within the intertidal zone. In contrast to these earlier experiments, the more recent experiments by Brown on competition among desert rodents were replicated sufficiently for statistical analysis and repeated a second time.

The reviews by Connell and Hairston provide a guide to field experimentation as it has been conducted in the past few decades. However, as we shall see in section VI, the need for experimentation at large scales is forcing ecologists to further expand their concept of experimental design.

Why did Brown's research team (see p. 295) create controls by completely fencing study plots and then cutting holes in their sides to allow free passage of rodents into and out of the plot Why not just compare the density of small rodents in the large granivore removal plots with their densities in the surrounding desert

Explanation

The mouse proof fences created around th...

Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255