Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Edition 7ISBN: 978-0077837280

Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Edition 7ISBN: 978-0077837280 Exercise 8

How many species are there This is one of the most fundamental questions that an ecologist can ask about a community. With increasing threats to biological diversity, species richness is also one of the most important community attributes we might measure. For instance, estimates of species richness are critical for determining areas suitable for conservation, for diagnosing the impact of environmental change on a community, or for identifying critical habitat for rare or threatened species. However, determining the number of species in a community is not a simple undertaking. Sound estimates of species richness for most taxa require a carefully designed, standardized sampling program. Here we will review some of the basic factors that an ecologist needs to consider when designing such a sampling program to gather information about species richness within and among communities.

Sampling Effort

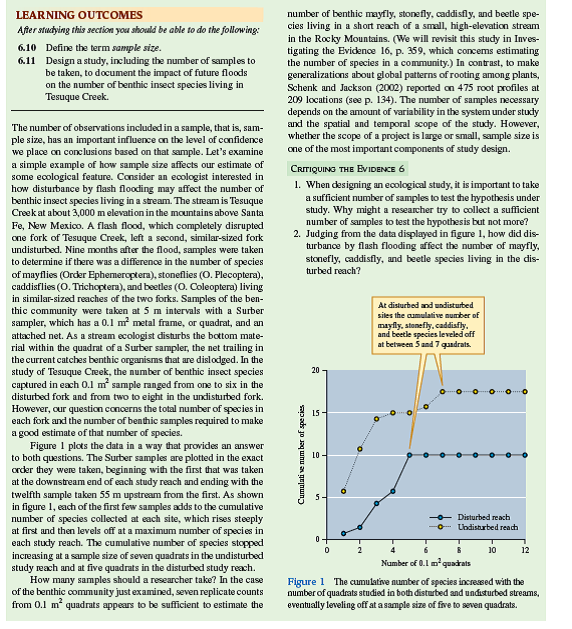

The number of species recorded in a sample of a community increases with higher sampling effort. We reviewed a highly simplified example of this in chapter 6 (see p. 136), where we considered how numbers of quadrats influenced estimates of species richness in the benthic community of a small Rocky Mountain stream. In that example, a relatively small sample size was required. However, often far more effort is required. For example, Petri Martikainen and Jari Kouki (2003) estimated that to verify the presence or absence of threatened beetle species in the boreal forests of Finland required a sample of over 400 beetle species. They also suggested that a sample of over 100,000 individual beetles may be required to assess just 10 forest areas in Finland for their suitability to serve as conservation areas for threatened beetle species. To reduce the sampling effort required to estimate species richness, community ecologists and conservationists often focus on groups of organisms that are reliable indicators of species richness.

Indicator Taxa

Because of the great cost and time of making thorough inventories of species diversity, ecologists have proposed a wide variety of taxa as indicators of overall biological diversity. Indicator taxa have generally been well-known and conspicuous groups of organisms such as birds and butterflies. However, it appears that indicator taxa need to be chosen with caution. For example, John Lawton of Imperial College in the United Kingdom and 12 colleagues (Lawton et al. 1998) attempted to characterize biological diversity along a disturbance gradient in the tropical forest of Cameroon, Africa, using indicator taxa. In addition to birds and butterflies, Lawton and his colleagues sampled flying beetles, beetles living in the forest canopy, canopy ants, leaf-litter ants, termites, and soil nematodes. They sampled these taxa from 1992 to 1994 and spent several more years sorting and cataloging the approximately 2,000 species collected. This work required approximately 10,000 s cientist hours. Unfortunately, the conclusion at the end of this massive study was that no one group serves as a reliable indicator of species richness for other taxonomic groups. Lawton and his colleagues estimated that their survey included from one-tenth to one-hundredth the total number of species in their study site. Citing their own experience, they concluded that characterizing the full biological diversity of just 1 hectare of tropical forest would require from 100,000 to 1 million scientist hours. As a consequence of these time constraints, ecologists will likely continue to focus their studies of diversity on smaller groups of taxa. However, even with a restricted taxonomic focus, it is important to standardize sampling across study communities.

Standardized Sampling

Standardizing sampling effort and technique is generally necessary to provide a valid basis for comparing species richness across communities. For example, Frode Ødegaard of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research took great care to standardize sampling as he compared species richness among plant-feeding beetles living in a tropical dry forest and in a tropical rain forest in Panama Standardized Sampling Standardizing sampling effort and technique is generally necessary to provide a valid basis for comparing species richness across communities. For example, Frode Ødegaard of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research took great care to standardize sampling as he compared species richness among plant-feeding beetles living in a tropical dry forest and in a tropical rain forest in Panama (Ødegaard 2006). Ødegaard sampled both forests from a canopy crane of the sort discussed in chapter 1 (see p. 7) that provided access to similar areas of forest (~0.8 ha). He standardized the amount of time he spent sampling each tree or vine and he used the same sampling techniques in both forests. Ødegaard also sampled the beetles on approximately the same number of plant species-50 species in the dry forest and 52 in the rain forest. His efforts resulted in the capture of very similar numbers of individual beetles in the two forests: 35,479 in dry forest versus 30,352 in rain forest. However, his collections in rain forest included 37% more beetle species than in dry forest: 1,603 species in rain forest versus 1,165 in dry forest. Because Ødegaard took care to standardize sampling, we can conclude that the species richness of plant-feeding beetles was probably higher at his rain forest study site. If his sampling efforts were uneven, we could not reach such a conclusion.

Why do most surveys of species diversity focus on restricted groups of relatively well-known organisms such as plants, mammals, and butterflies

Sampling Effort

The number of species recorded in a sample of a community increases with higher sampling effort. We reviewed a highly simplified example of this in chapter 6 (see p. 136), where we considered how numbers of quadrats influenced estimates of species richness in the benthic community of a small Rocky Mountain stream. In that example, a relatively small sample size was required. However, often far more effort is required. For example, Petri Martikainen and Jari Kouki (2003) estimated that to verify the presence or absence of threatened beetle species in the boreal forests of Finland required a sample of over 400 beetle species. They also suggested that a sample of over 100,000 individual beetles may be required to assess just 10 forest areas in Finland for their suitability to serve as conservation areas for threatened beetle species. To reduce the sampling effort required to estimate species richness, community ecologists and conservationists often focus on groups of organisms that are reliable indicators of species richness.

Indicator Taxa

Because of the great cost and time of making thorough inventories of species diversity, ecologists have proposed a wide variety of taxa as indicators of overall biological diversity. Indicator taxa have generally been well-known and conspicuous groups of organisms such as birds and butterflies. However, it appears that indicator taxa need to be chosen with caution. For example, John Lawton of Imperial College in the United Kingdom and 12 colleagues (Lawton et al. 1998) attempted to characterize biological diversity along a disturbance gradient in the tropical forest of Cameroon, Africa, using indicator taxa. In addition to birds and butterflies, Lawton and his colleagues sampled flying beetles, beetles living in the forest canopy, canopy ants, leaf-litter ants, termites, and soil nematodes. They sampled these taxa from 1992 to 1994 and spent several more years sorting and cataloging the approximately 2,000 species collected. This work required approximately 10,000 s cientist hours. Unfortunately, the conclusion at the end of this massive study was that no one group serves as a reliable indicator of species richness for other taxonomic groups. Lawton and his colleagues estimated that their survey included from one-tenth to one-hundredth the total number of species in their study site. Citing their own experience, they concluded that characterizing the full biological diversity of just 1 hectare of tropical forest would require from 100,000 to 1 million scientist hours. As a consequence of these time constraints, ecologists will likely continue to focus their studies of diversity on smaller groups of taxa. However, even with a restricted taxonomic focus, it is important to standardize sampling across study communities.

Standardized Sampling

Standardizing sampling effort and technique is generally necessary to provide a valid basis for comparing species richness across communities. For example, Frode Ødegaard of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research took great care to standardize sampling as he compared species richness among plant-feeding beetles living in a tropical dry forest and in a tropical rain forest in Panama Standardized Sampling Standardizing sampling effort and technique is generally necessary to provide a valid basis for comparing species richness across communities. For example, Frode Ødegaard of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research took great care to standardize sampling as he compared species richness among plant-feeding beetles living in a tropical dry forest and in a tropical rain forest in Panama (Ødegaard 2006). Ødegaard sampled both forests from a canopy crane of the sort discussed in chapter 1 (see p. 7) that provided access to similar areas of forest (~0.8 ha). He standardized the amount of time he spent sampling each tree or vine and he used the same sampling techniques in both forests. Ødegaard also sampled the beetles on approximately the same number of plant species-50 species in the dry forest and 52 in the rain forest. His efforts resulted in the capture of very similar numbers of individual beetles in the two forests: 35,479 in dry forest versus 30,352 in rain forest. However, his collections in rain forest included 37% more beetle species than in dry forest: 1,603 species in rain forest versus 1,165 in dry forest. Because Ødegaard took care to standardize sampling, we can conclude that the species richness of plant-feeding beetles was probably higher at his rain forest study site. If his sampling efforts were uneven, we could not reach such a conclusion.

Why do most surveys of species diversity focus on restricted groups of relatively well-known organisms such as plants, mammals, and butterflies

Explanation

The sampling of any respective area requ...

Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255