Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Edition 7ISBN: 978-0077837280

Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Edition 7ISBN: 978-0077837280 Exercise 19

Throughout this series of discussions of investigating the evidence, we have emphasized one main source of evidence- original research. While original research is the foundation on which science rests, our emphasis has neglected one of the most valuable sources of information, the published literature. A researcher in any discipline needs to keep up with developments in his or her areas of interest and in related areas. In addition, some researchers may use published literature to weigh the evidence for or against some hypothesis or theory. In the section in chapter 13 titled "Evidence for Competition in Nature" (see p. 000), we reviewed three studies that took such an approach. Students of ecology may use published literature to learn more about a particular subject, to read additional papers by researchers whose work interests them, or to do literature surveys in support of their own independent research. As pointed out in the preface of this book, however, the explosive pace of scientific discovery makes staying current very difficult. Fortunately, there are now many databases and searching tools that can help.

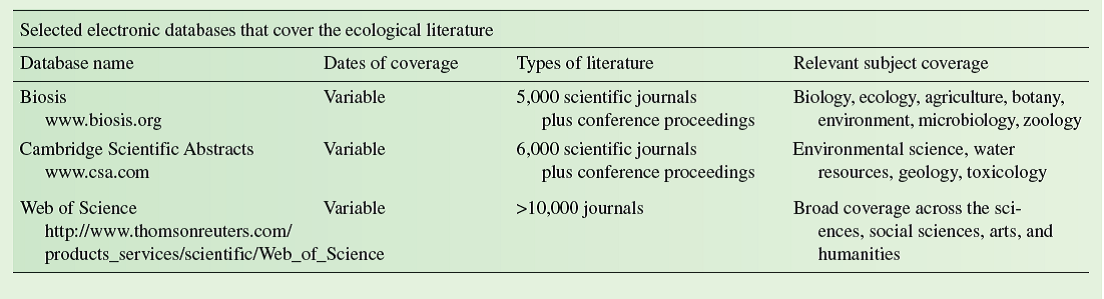

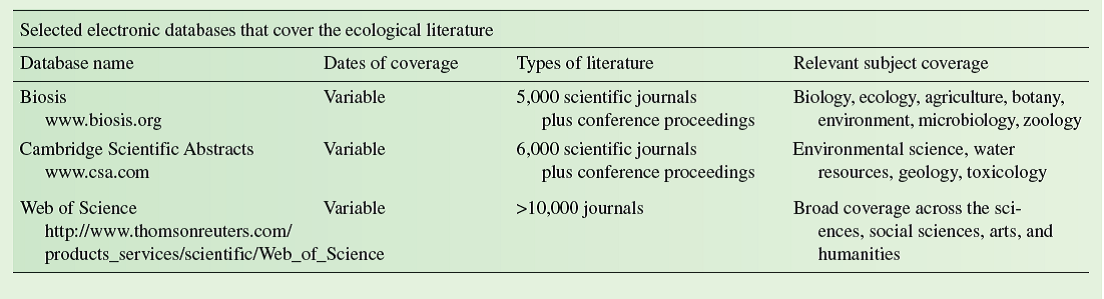

The databases available for searching ecological literature are far too many to review here. So, we'll focus on three contemporary ones: Biosis, Cambridge Scientific Abstracts, and SciSearch, which are widely available in university libraries and include many journals of significance to ecology. Some of their characteristics are listed in the accompanying table.

The important point here is that these databases provide access to millions of published papers often covering several decades of research. Of course, few people would want to spend the time laboriously sorting through all those articles. Fortunately, each of these databases includes a powerful search tool that will help you locate articles of interest. Let's consider some basic tips on how to use these tools to conduct an effective search.

You should generally begin your search by summarizing your subject or research interest. Next, divide your subject into major concepts or key terms. Be sure to think of alternative terms for the same subject-for example, beetles or Coleoptera, daisy or Asteraceae, competition or interference. Next determine the time period in which you are interested. For instance, do you want only the most current literature on your subject or do you want all literature available in the database

Once you have your terms listed and have selected a time period, try a search using one or more terms. If you get too many references, too few references, or unwanted references, you can use Boolean Logical Operators to adjust your search. The main Boolean Logical Operators are and, or, and not. The operator or will broaden your search and will generally yield more references. For instance, the search specified by "daisy or Asteraceae" will retrieve references containing either daisy or Asteraceae. In contrast the operator and will narrow your search. The search specified by "daisy or Asteraceae and desert" will retrieve references containing either daisy or Asteraceae, but restrict the list of references to those concerned with these flowers in desert areas. The search specified by "daisy or Asteraceae and alpine" would yield literature on these flowers in alpine zones. If you want to exclude certain types of references from your search, you may choose to use the operator not. For example the search "daisy or Asteraceae not sunflower" will exclude references that include the term sunflower.

Another useful tool for refining searches is the wild card. A wild card is used to locate references including a particular word or term with alternative endings. For example, you may encounter references to the insect order to which beetles belong as Coleoptera, coleopteran, or coleopterans. In the three databases listed below, an asterisk, * , is generally used as a wild card. In all of these databases, the search term coleoptera * would locate references that included the terms Coleoptera, coleopteran, or coleopterans. Similarly, the search term dais * would retrieve references to both daisy and daisies.

This review is intended to suggest only general guidelines to searching literature. There are many other databases besides the ones listed here, and the creators of all of them work very hard to improve the functioning of their products. As a consequence, the operating details of the various databases are highly dynamic. Therefore, you should periodically review the tips and instructions provided with any database that you might use. The main point of this discussion is to open a door to the rich world of ecological literature, to the world of discovery. Exploring that world can quickly extend your knowledge of the discipline of ecology far beyond the introduction provided by this textbook.

When and why may it be important to broaden a literature search

The databases available for searching ecological literature are far too many to review here. So, we'll focus on three contemporary ones: Biosis, Cambridge Scientific Abstracts, and SciSearch, which are widely available in university libraries and include many journals of significance to ecology. Some of their characteristics are listed in the accompanying table.

The important point here is that these databases provide access to millions of published papers often covering several decades of research. Of course, few people would want to spend the time laboriously sorting through all those articles. Fortunately, each of these databases includes a powerful search tool that will help you locate articles of interest. Let's consider some basic tips on how to use these tools to conduct an effective search.

You should generally begin your search by summarizing your subject or research interest. Next, divide your subject into major concepts or key terms. Be sure to think of alternative terms for the same subject-for example, beetles or Coleoptera, daisy or Asteraceae, competition or interference. Next determine the time period in which you are interested. For instance, do you want only the most current literature on your subject or do you want all literature available in the database

Once you have your terms listed and have selected a time period, try a search using one or more terms. If you get too many references, too few references, or unwanted references, you can use Boolean Logical Operators to adjust your search. The main Boolean Logical Operators are and, or, and not. The operator or will broaden your search and will generally yield more references. For instance, the search specified by "daisy or Asteraceae" will retrieve references containing either daisy or Asteraceae. In contrast the operator and will narrow your search. The search specified by "daisy or Asteraceae and desert" will retrieve references containing either daisy or Asteraceae, but restrict the list of references to those concerned with these flowers in desert areas. The search specified by "daisy or Asteraceae and alpine" would yield literature on these flowers in alpine zones. If you want to exclude certain types of references from your search, you may choose to use the operator not. For example the search "daisy or Asteraceae not sunflower" will exclude references that include the term sunflower.

Another useful tool for refining searches is the wild card. A wild card is used to locate references including a particular word or term with alternative endings. For example, you may encounter references to the insect order to which beetles belong as Coleoptera, coleopteran, or coleopterans. In the three databases listed below, an asterisk, * , is generally used as a wild card. In all of these databases, the search term coleoptera * would locate references that included the terms Coleoptera, coleopteran, or coleopterans. Similarly, the search term dais * would retrieve references to both daisy and daisies.

This review is intended to suggest only general guidelines to searching literature. There are many other databases besides the ones listed here, and the creators of all of them work very hard to improve the functioning of their products. As a consequence, the operating details of the various databases are highly dynamic. Therefore, you should periodically review the tips and instructions provided with any database that you might use. The main point of this discussion is to open a door to the rich world of ecological literature, to the world of discovery. Exploring that world can quickly extend your knowledge of the discipline of ecology far beyond the introduction provided by this textbook.

When and why may it be important to broaden a literature search

Explanation

Literature survey is an important part o...

Ecology 7th Edition by Manuel Molles

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255