Environmental Science 15th Edition by Scott Spoolman,Tyler Miller

Edition 15ISBN: 978-1305090446

Environmental Science 15th Edition by Scott Spoolman,Tyler Miller

Edition 15ISBN: 978-1305090446 Exercise 17

THE GULF OF MEXICO'S ANNUAL DEAD ZONE

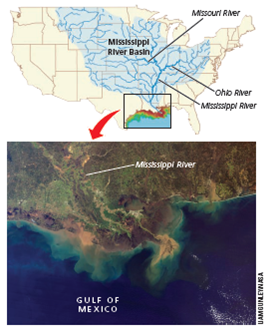

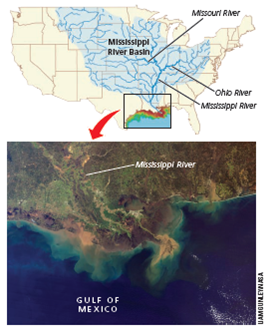

The Mississippi River basin (Figure 11.A, map) lies within 31 states and contains almost two-thirds of the continental U.S. land area. With more than half of all U.S. croplands, it is one of the world's most productive agricultural regions. However, water draining into the Mississippi River and its tributaries from farms, cities, factories, and sewage treatment plants in this huge basin contains sediments and other pollutants that end up in the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 11.A, photo)-a major supplier of the country's fish and shellfish.

Each spring and summer, this huge input of plant nutrients, mostly nitrates from crop fertilizers, enters the northern Gulf of Mexico and overfertilizes the coastal waters of the U.S. states of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. One result is an explosion of populations of phytoplankton (mostly algae) that eventually die and fall to the sea floor. Hordes of oxygen-consuming bacteria that decompose the phytoplankton remains deplete the dissolved oxygen in the Gulf's bottom layer of water.

The huge volume of water affected by this seasonal event is called a dead zone because it contains little animal marine life. Its low oxygen levels (Figure 11.B) drive away faster-swimming marine organisms and suffocate bottom-dwelling fish, crabs, oysters, and shrimp that cannot move to less polluted areas. Large amounts of sediment, mostly from soil eroded from the Mississippi River basin, can also kill bottom-dwelling forms of animal aquatic life. The dead zone appears each spring and grows until fall when storms churn the water and redistribute dissolved oxygen to the Gulf bottom.

The size of the Gulf of Mexico's annual dead zone depends primarily on the amount of water flowing into the Mississippi River each year. In years with ample rainfall and snowmelt, such as 2003, it has covered an area as large as the state of Massachusetts-27,300 square kilometers (10,600 square miles). In 2013, a severe drought year in parts of the country, it covered a smaller area of about 15,125 square kilometers (5,840 square miles)-about the size of the state of Connecticut.

The annual Gulf of Mexico dead zone (one of about 400 dead zones found throughout the world) represents a disruption of the nitrogen cycle (see Figure 3.15, p. 54) caused primarily by human activities. It happens because huge quantities of nitrogen from nitrate fertilizers are added to ecosystems such as the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico much faster than the nitrogen cycle can remove them. As a result, by producing crops for food and ethanol to fuel cars in the vast Mississippi basin, we end up disrupting coastal aquatic life and seafood production in the Gulf of Mexico.

Because of the size and agricultural importance of the Mississippi River basin, there is no easy solution to the problem of severe cultural eutrophication of this coastal zone. The best hope lies in preventive measures, including applying less fertilizer on farms upstream, injecting fertilizer below the soil surface, and using controlledrelease fertilizers that have waterinsoluble coatings. Other such measures include planting strips of forests and grasslands along waterways to soak up excess nitrogen, restoring Gulf Coast wetlands that once filtered some of the plant nutrients, and creating wetlands between crop fields and streams emptying into the Mississippi River. Another measure would be to reduce or eliminate government subsidies for growing corn to make ethanol.

Critical Thinking

Which three of the preventive measures described above do you believe would be the most effective? Explain.

FIGURE 11.B The colorized area in this satellite image of the northern Gulf of Mexico represents the seasonal dead zone of 2012 with the red area having the lowest oxygen level.

The Mississippi River basin (Figure 11.A, map) lies within 31 states and contains almost two-thirds of the continental U.S. land area. With more than half of all U.S. croplands, it is one of the world's most productive agricultural regions. However, water draining into the Mississippi River and its tributaries from farms, cities, factories, and sewage treatment plants in this huge basin contains sediments and other pollutants that end up in the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 11.A, photo)-a major supplier of the country's fish and shellfish.

Each spring and summer, this huge input of plant nutrients, mostly nitrates from crop fertilizers, enters the northern Gulf of Mexico and overfertilizes the coastal waters of the U.S. states of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. One result is an explosion of populations of phytoplankton (mostly algae) that eventually die and fall to the sea floor. Hordes of oxygen-consuming bacteria that decompose the phytoplankton remains deplete the dissolved oxygen in the Gulf's bottom layer of water.

The huge volume of water affected by this seasonal event is called a dead zone because it contains little animal marine life. Its low oxygen levels (Figure 11.B) drive away faster-swimming marine organisms and suffocate bottom-dwelling fish, crabs, oysters, and shrimp that cannot move to less polluted areas. Large amounts of sediment, mostly from soil eroded from the Mississippi River basin, can also kill bottom-dwelling forms of animal aquatic life. The dead zone appears each spring and grows until fall when storms churn the water and redistribute dissolved oxygen to the Gulf bottom.

The size of the Gulf of Mexico's annual dead zone depends primarily on the amount of water flowing into the Mississippi River each year. In years with ample rainfall and snowmelt, such as 2003, it has covered an area as large as the state of Massachusetts-27,300 square kilometers (10,600 square miles). In 2013, a severe drought year in parts of the country, it covered a smaller area of about 15,125 square kilometers (5,840 square miles)-about the size of the state of Connecticut.

The annual Gulf of Mexico dead zone (one of about 400 dead zones found throughout the world) represents a disruption of the nitrogen cycle (see Figure 3.15, p. 54) caused primarily by human activities. It happens because huge quantities of nitrogen from nitrate fertilizers are added to ecosystems such as the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico much faster than the nitrogen cycle can remove them. As a result, by producing crops for food and ethanol to fuel cars in the vast Mississippi basin, we end up disrupting coastal aquatic life and seafood production in the Gulf of Mexico.

Because of the size and agricultural importance of the Mississippi River basin, there is no easy solution to the problem of severe cultural eutrophication of this coastal zone. The best hope lies in preventive measures, including applying less fertilizer on farms upstream, injecting fertilizer below the soil surface, and using controlledrelease fertilizers that have waterinsoluble coatings. Other such measures include planting strips of forests and grasslands along waterways to soak up excess nitrogen, restoring Gulf Coast wetlands that once filtered some of the plant nutrients, and creating wetlands between crop fields and streams emptying into the Mississippi River. Another measure would be to reduce or eliminate government subsidies for growing corn to make ethanol.

Critical Thinking

Which three of the preventive measures described above do you believe would be the most effective? Explain.

FIGURE 11.B The colorized area in this satellite image of the northern Gulf of Mexico represents the seasonal dead zone of 2012 with the red area having the lowest oxygen level.

Explanation

Cultural eutrophication refers to the ph...

Environmental Science 15th Edition by Scott Spoolman,Tyler Miller

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255