Corporate Communication 6th Edition by Paul Argenti

Edition 6ISBN: 978-0073403175

Corporate Communication 6th Edition by Paul Argenti

Edition 6ISBN: 978-0073403175 Exercise 4

Disney's America Theme Park: The Third Battle of Bull Run

When you wish upon a star, makes no difference who you are. Anything your heart desires will come to you. If your heart is in your dreams, no request is too extreme...

-Jiminy Cricket

On September 22, 1994, Michael Eisner, CEO of the Walt Disney Company, one of the most powerful and well-known media conglomerates in the world, stared out the window of his Burbank office, contemplating the current situation surrounding the Disney's America theme park. Ever since November 8, 1993, when The Wall Street Journal first broke the news that Disney was planning to build a theme park near Washington, D.C., ongoing national debate over the location and concept of the $650 million park had caused tremendous frustration. Eisner thought back over the events of the past year. How could his great idea have run into such formidable resistance?

THE CONTROVERSY COMES TO A HEAD

Eisner's secretary had clipped several newspaper articles covering two parades that took place on September 17. In Washington, D.C., several hundred Disney opponents from over 50 anti-Disney organizations had marched past the White House and rallied on the National Mall in protest of the park. On the same day in the streets of Haymarket, Virginia, near the proposed park site, Mickey Mouse and 101 localchildren dressed as Dalmatians had appeared in a parade that was filled with pro-Disney sentiment. Eisner was particularly struck by the contrast between the two pictures: one showing an anti-Disney display from the National Mall protest and another of Mickey and Minnie Mouse being driven through the streets of Haymarket during the exuberant community parade.

Despite the controversy depicted in the press, on September 21, Prince William County, Virginia, planning commissioners had recommended local zoning approval for Disney's America, and regional transportation officials had authorized $130 million in local roads to serve it. It appeared very likely that the project would win final zoning approval in October. At the state level, Virginia's Governor George Allen continued his strong support of the park's development.

Over the past three weeks, however, Eisner had been ruminating over a phone call he received in late August from John Cooke, President of the Disney Channel since 1985. Although Cooke had no responsibility for Disney's America, he had more experience in the Washington, D.C. political scene than any of Disney's other highest-ranking managers and was one of Eisner's most trusted executives. Cooke was not encouraging about the park's prospects. Quite familiar with many of the park's opponents, he believed they would not give up the fight under any circumstances. Given the anti-Disney coalition's considerable financial resources, the nationally publicized anti-Disney campaign could go on indefinitely, inflicting immeasurable damage on Disney's fun, family image. Cooke advised Eisner to think very seriously about ending the project.

Since the mid-1980s, Eisner's business strategy was to revitalize Disney by broadening its brand into new ventures. Although promising at first, now the wisdom of some of the ventures seemed less certain. The worst example, EuroDisney, the new Disney park located outside Paris, continued to flounder. The numbers for fiscal year 1994, due in just a couple of days on September 30, didn't look promising. Estimates said net income would be down to $300 million from $800 million the year before, mostly because EuroDisney lost $515 million from operations and $372 million from a related accounting charge.

The good news was that due to cost cutting, EuroDisney's losses were actually less than in the previous year, while the bad news was that attendance was also down. Prince al-Waleed bin Talal bin Adulaziz of Saudi Arabia had agreed to buy 24 percent of the park and build a convention center there, thus relieving some of the financial pressure, but it seemed that the negative press coverage of that park's troubles would never end.

The Disney's America problem was particularly bothersome, however. Eisner realized that the controversy surrounding the park, coupled with the many other highly publicized problems of 1994, was damaging Disney's image. Due to publicity about its highly visible corporate problems, Disney's image as a business threatened to tarnish its reputation for family-friendly fun and fantasy.

Personally, Eisner was particularly fond of the Disney's America concept. He had helped develop the original idea and had personally championed it within the Disney organization. He recalled the early meetings during which several Disney executives, including himself, had brainstormed an American history concept. He and the other executives had strongly believed that Disney had the unique capability of designing an American history theme park that would draw on the company's technical expertise and offer guests an entertaining, educational, and emotional journey through time. They envisioned guests, adults and children alike, embracing a park dedicated to telling the story of U.S. history. Eisner had hoped the park would be part of the personal legacy he would leave behind at Disney. As he told a Washington Post reporter, "This is the one idea I've heard that is, in corporate locker room talk, what's known as a no-brainer."

THE DISNEY'S AMERICA CONCEPT AND LOCATION

The idea of building an American history theme park originated in 1991 when Eisner and other Disney executives attended a meeting at Colonial Williamsburg in south eastern Virginia. The executives were impressed by the restored pre-Revolutionary capital. Disney had already been thinking about locations for theme parks that were on a somewhat smaller scale than the company's massive ones. Visiting Williamsburg helped Disney make the connection to a new park based on historical themes.

Disney's attention soon shifted focus to Washington, D.C. As the third-largest tourist market in the United States and the center of American government, the nation's capital seemed a natural location for an American history park. The abundance of historical sites in the area broadened its appeal as a center of American history. Disney's other parks were located on the fringes of developed urban centers (Anaheim, Orlando, Tokyo, and Paris). The parks gained advantages from their proximity to urban centers, but due to their peripheral locations, Disney was able to acquire lower-priced land and ensure a safe environment for visitors, far from inner-city congestion and crime.

Disney needed a location with easy access to an airport and an exit off an interstate highway. Executives hoped to find land that had already been zoned for development as well as local and state politicians who would be open to economic growth. In Prince William County, located in the heart of Virginia's Piedmont region, Disney found all these things. Dulles International Airport was located just east of Prince William County. U.S. Interstate 66 (I-66), the main traffic artery connecting Washington, D.C., with its western suburbs, could transport tourists straight from Washington's monuments and museums into Prince William County, a distance of about 35 miles.

The political and economic context also made Prince William County attractive to Disney. Virginia had long been a pro-growth state, and its governors were constantly under pressure to bring in new business. Democratic Governor Doug Wilder would leave office in November 1993, having lost some notable campaigns to bring growth to Virginia's economy. Polls showed that he would likely be replaced by Republican George Allen, the son of a former Washington Redskins American football coach and a graduate of the University of Virginia. If elected, Allen would be under instant pressure to create state economic growth. Most Prince William County officials were also "pro-growth," though not well prepared for it. The county's growing population of middle-class residents (up 62 percent since 1980) paid the highest taxes in the state of Virginia due to a dearth of economic development within the county. The Virginia legislature set an ambitious goal in 1990 to attract 14,000 jobs and $1 billion in nonresidential growth to the county to fund more and better schools and county administrative services, in addition to reducing residential taxes paid by each family.

In the spring of 1993, Peter Rummell, President of Disney Design and Development, which included the famous Imagineering group, as well as the real estate division, identified 3,000 acres in Prince William County near the small town of Haymarket (population 483). The largest property was a 2,300-acre plot of land, the Waverly Tract, owned by a real estate subsidiary of the Exxon Corporation. Waverly was already zoned for mixed-use development of homes and office buildings, yet due to a weak real estate market, Exxon had never broken ground on the undeveloped farmland. For a modest holding price, Exxon was willing to option the property. Using a scheme that had worked years before in Orlando, the Disney real estate group bought or put options on Waverly and the remaining 3,000 acres without revealing the company's corporate identity in any of the transactions.

THE VIRGINIA PIEDMONT

The northeast corner of Virginia comprises the Piedmont region. The region contains countless significant sites related to U.S. history, including, for example, the preserved homes of four of the first five U.S. presidents: Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. According to Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough, "This is the ground of our Founding Fathers. These are the landscapes-small towns, churches, fields, mountains, creeks, and rivers-that speak volumes."3 Thomas Jefferson loved the agrarian life he found on the farms east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. In his letters, he exulted over the region's "delicious spring," "soft genial temperatures," and good soil.

The region is also home to more than two-dozen Civil War battlefields. The U.S. Civil War was fought largely over the issue of slavery, pitting northern states against the southern states that had seceded from the union. Just a National Battlefield Park, land that is protected and preserved by the U.S. National Park Service, commemorating two major Civil War battles. The first battle in 1861 was the Civil War's first major land engagement. The second, in 1862, marked the beginning of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the North. On what would become some of the bloodiest soil in U.S. history, Lee reflected at Bull Run in 1861, "The views are so magnificent, the valleys so beautiful, the scenery so peaceful. What a glorious world the Almighty has given us. How thankless and ungrateful we are, and how we labor to mar His gifts."

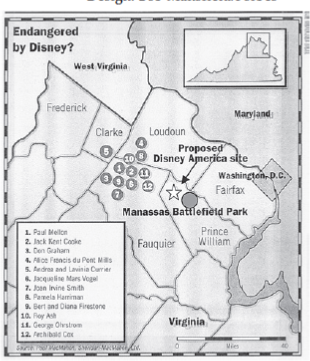

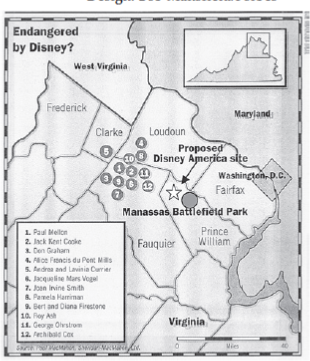

Although largely rural and predominantly middle class, the region was also notable as home to some of America's most wealthy and influential citizens. The largest estates suggested the presence of privilege at every turn: perfect fences built from stone or wood, carefully manicured pastures, large barns requiring lots of hired help, a few private landing strips, and long private lanes lined with boxwood or dogwood that led to magnificent private homes. Exhibit 9.1 provides a map showing the locations of some of the area's most wealthy homeowners.

The Piedmont also had a history of successfully fighting local development projects. In the late 1970s, the Marriott Corporation had proposed building a large amusement park, and, in the late 1980s, a development group had planned to develop a major shopping mall in the area. Both projects were defeated by local opposition.

DISNEY'S PLANS REVEALED

To keep its land acquisition secret, Disney had done little to work with local government and communities, but by late October of 1993, Eisner learned that Disney's plans had begun to leak. It would only be a matter of days before the news would hit the media, so in the meantime Disney had to act quickly. Behind the scenes, Eisner contacted outgoing Governor Wilder and Governor-elect Allen. Both gave their immediate support and agreed to attend a public announcement scheduled for November 11. The company hired a local real estate law firm, and also retained the services of Jody Powell, former Press Secretary to President Jimmy Carter, who ran the Powell Tate public relations firm.

EXHIBIT 9.1 The Third Battle of Bull Run: The Disney's America Theme Park. Proximity of Disney's America Site to Several Wealthy Residents. Design: Bob Mansfield/Forbes

On November 8, 1993, a brief item appeared in The Wall Street Journal stating that Disney was planning to build a theme park somewhere in Virginia. That same day, Disney officials confirmed the story but provided no additional details. The next day, a Washington Post reporter identified Prince William County as the targeted area. Disney spokespeople confirmed the location and added some details. Disney officials briefed reporters and legislators, stating that they had investigated possible obstacles to the project, including environmental and historic preservation concerns, and believed there would be no serious problems. They also stated that they had studied traffic patterns on I-66 and believed additional theme park traffic would not exacerbate rush-hour congestion. Because 65 percent of Prince William County residents commuted to jobs in other northern Virginia counties, traffic congestion was a primary concern. On November 10, the Post ran the first full news story, headlined "Disney Plans Theme Park Here; Haymarket, VA: Project to Include Mall, Feature American History."

As local discussion increased, Disney held an upbeat news conference on November 11 and also issued a press release. Rummell, flanked by the governors and local officials, revealed an architectural model of the theme park and the surrounding development plans. The park logo featured a bold close-up of a stylized bald eagle rendered in navy blue, draped in red and white striped bunting, and with the words, "Disney Is America" emblazoned in gold across the eagle's chest.

Disney's America was presented as a "totally new concept... to celebrate those unique

American qualities that have been our country's strengths and that have made this nation the beacon of hope to people everywhere." Disney would draw upon its entertainment experience in multimedia and theme park attractions. Disney officials emphasized the park's focus on the Civil War. Guests would enter the park through a detailed Civil War-era village and then ride a steam train to explore nine areas, each devoted to an episode from American history. One of these included a Civil War fort, complete with battle reenactments. Other exhibits included "We the People," depicting the immigrant experience at Ellis Island, and "Enterprise," a factory town featuring a high-speed thrill attraction called "The Industrial Revolution."

Disney officials predominantly sold the park on its economic benefits to the local area, stating that the park would directly generate about 3,000 permanent jobs along with 16,000 jobs indirectly. Around the park, the company would develop resort hotels, an RV park, a 27-hole public golf course, a commercial complex with retail and office space, and 2,300 homes.11 Disney projected $169 million in tax revenues for the first 10 years after the park opened in 1998 and nearly $2 billion over its first 30 years. In addition, Disney would donate land for schools and a library and reserve up to 40 percent green space as a buffer around the core recreational area.

In part, the announcement came off better in print than at the conference. In the press release, Bob Weis, Senior Vice President of Walt Disney Imagineering, was quoted as saying, "Beyond the rides and attractions for which Disney is famous, the park will be a venue for people of all ages, especially the young, to debate and discuss the future of our nation and to learn more about its past by living it." In the conference, however, Weis said of the attractions, "We want to make you a Civil War soldier. We want to make you feel what it was like to be a slave, or what it was like to escape through the Underground Railroad." Weis's intended meaning was to refer to the new technology of virtual reality that would be used, but critics quickly jumped on the statement. Washington Post columnist Courtland Milloy contrasted the description to "authentic history" that would have to portray atrocities like slave whippings and rape.14 Author William Styron wrote that he believed the comment suggested that slavery was somehow a subject for fun or that the escape route used for slaves was similar to a subway system.

PIEDMONT OPPOSITION

Almost immediately after Disney confirmed its plans to build a park in Prince William County, anti-Disney forces began organizing their opposition. To many who were alarmed, the plans seemed already so well-developed that they gave the impression of a fait accompli. Just days after Disney's formal announcement, a meeting was held at the home of Charles S. Whitehouse, a retired foreign service officer who had owned property in the Virginia hunt country since the early 1960s. The dozen guests included William D. Rogers, former Undersecretary of State under Henry Kissinger and now a senior partner in a powerful Washington law firm; Joel McCleary, a former aide in the Carter White House and former Treasurer of the Democratic National Committee; and Lavinia Currier, great-granddaughter of Pittsburgh financier Andrew Mellon. William Backer, a former New York advertising executive who had created slogans for Coca Cola ("Coke- It's the Real Thing") and Miller Beer ("If you've got the time, we've got the beer"), also attended. The group worried that the proposed development would undermine the upper Piedmont's "traditional character and visual order."

The phrase came from the charter of the Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC), a rural-preservation group co-chaired by Whitehouse. Many of Whitehouse's guests had donated considerable amounts of time and money to the organization, which fought development and bought land and easements to preserve the area. The PEC was originally founded in 1927 by a group of prominent landowners. Over the years, it fought successfully against uranium mining and plans for a "western bypass" highway.

The group discussed the options for stopping Disney's encroachment upon the hunt country. There was the possibility of derailing the project during the Virginia legislature's next session. Rogers discussed some of the legal options. Backer suggested a negative publicity campaign, possibly at a national level, to force an image-conscious company like Disney to retreat. He argued for a subtle approach rather than a straight-on NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) campaign. He didn't want the opposition campaign to be viewed simply as a group of wealthy landowners who wanted to prevent a theme park from disturbing their fox hunting. As the meeting ended, Backer agreed to come up with a slogan.

A few days later, Backer presented his "Disney, Take a Second Look" slogan to the group. Backer's angle was to convince Disney that it should reassess the idea of building a theme park amid the beauty of the Piedmont. Although the campaign addressed Disney directly, it would remind anyone who saw it of the Piedmont's unspoiled and now-threatened natural beauty. Within a few days, the slogan was running in radio ads and incorporated on a letterhead. The logo accompanying the slogan showed a balloon, with a barn and farmhouse inside, drifting away in the breeze.

This initial meeting was followed by dozens of others in the coming weeks and months. One week after the gathering at the Whitehouse home, over 500 people attended a meeting at the Grace Episcopal Church in The Plains, Virginia, about seven miles west of the Disney site. The meeting's attendants represented a wide range of economic backgrounds, but they were united in their preference for the rural life they enjoyed.

Megan Gallagher, Whitehouse's Co- Chairman of the Piedmont Environmental ?Council, led the meeting, reminding the group of other local protest movements that had stopped big projects. Other speeches rounded out the audience's concerns: the park's estimated 9 million annual visitors would spark low-density ancillary development like that around Anaheim and Orlando. The pristine countryside would be overcome by cheap hotels, restaurants, and strip malls. Already problematic traffic congestion would be exacerbated. The park would create low-wage jobs and not provide the tax base that the Disney plan promised. During the meeting, the Piedmont Environmental Council, which had already committed $100,000 of its $700,000 annual budget to the project, emerged as the leading opposition group.

A few days after the meeting at Grace Episcopal Church, another meeting organized by the Prince Charitable Trusts of Chicago, another land preservation group, was held at a local restaurant. This meeting brought together several regional and national environmental groups concerned about the Disney's America project. Eventually, the Prince Charitable Trusts would give over $400,000 to 14 different anti-Disney groups that conducted studies, gave press conferences, and attacked Disney from every possible environmental angle. The largest grant went to the National Growth Management League, which mounted a local advertising campaign under the name "Citizens Against Gridlock." The campaign depicted I-66, already one of northern Virginia's busiest and congested highways, as "Disney's parking lot."

In early December, the PEC held a news conference in a Washington hotel to increase the reach of its "Second Look" campaign. It retained a prominent Washington law firm as well as a public relations firm. The group began recruiting and organizing dozens of volunteers. It sent out a fundraising letter seeking $500,000 in contributions. It also commissioned experts to assess the park's impact on the environment, urban sprawl, traffic, employment, and property taxes.

DISNEY'S CAMPAIGN

Soon after the public announcement, Disney undertook concerted efforts to win over state and local government, as well as constituencies within proximity of the proposed site. Virginia's new Governor, George Allen, immediately promoted the Disney project. He believed Disney's worldwide reputation would make Virginia an international tourist destination, bringing millions of travelers to the state. In numerous press releases, Allen endorsed Disney's belief that the project would create 19,000 jobs and bring millions of new tax dollars to state and municipal coffers.

By early January, Disney asked the state to bear some of the costs of the new park. Disney requested $137 million in state highway improvements and $21 million to train workers, move equipment from Orlando, pay for advertising, and put up highway signs directing tourists to the park. These funds would have to be guaranteed by the end of the current state legislative session to allow Disney to move ahead with development in early 1995. Now focusing on Virginia's state capital, Disney retained a well-connected Richmond law firm to handle its lobbying efforts. It also hired a Richmond event-planning firm to organize two large receptions. Lobbying expenses alone reached almost $450,000, including $32,000 for receptions and $230 for the Mickey Mouse ties given to state legislators.

Allen supported Disney's request and argued the highway improvements Disney planned would ease traffic problems that already existed in northern Virginia, in addition to accommodating the extra traffic generated by the park. The state's support of the project, he said, would send a message that Virginia was "open for business."

Disney officials met with African-American legislators and promised to ensure that minorities got a good shot at contracts and jobs. They invited a dozen officials from area museums and historic sites, including Monticello and Colonial Williamsburg, to a meeting in Orlando to discuss their plans for portraying history in the northern Virginia park. In Richmond, Disney lobbyists portrayed opponents as wealthy landowners who simply did not want Disney in their backyards.

Disney sought and received strong support from the Prince William business community, especially realtors, contractors, hotels, restaurants, and utility companies. The Disney staff also poured tremendous effort into harnessing the support of local citizens, spending hours preaching the message of neighborliness to local groups. Groups formed to support the park, including the Welcome Disney Committee, Friends of the Mouse, Youth for Disney, and Patriots for Disney. Members of these groups attended state legislative hearings, gave testimony, and handed out bumper stickers and buttons. Disney sent newsletters to 100,000 local households and retained a second Washington public relations firm to handle grassroots support.

Disney also entered negotiations with the National Park Service at the Manassas park, which was three miles away. The company agreed to limit the height of its structures to 140 feet so they would not be visible from the park and to develop a special transit bus system that would transport 20 percent of Disney guests and 10 percent of employees. The company promised to promote historic preservation and the Manassas National Battlefield Park within Disney's America and immediately donated money to an allied nonprofit group.

THE PEC'S CAMPAIGN

The PEC mounted a strong effort in Richmond as well, including hiring two full-time lobbyists. Its campaign was based on the premise that the park was a bad business deal for Virginia. The PEC claimed that the park would generate fewer jobs than Disney and Governor Allen had promised-6,300 rather than 19,000- and that the jobs would not pay well. They accused Allen of exaggerating the tax benefits. They emphasized the traffic and air pollution that would be caused by the park. They also suggested 32 other sites in the Washington area that would be more suited to the project than the current site. Finally, they suggested that the state should not have to fund any of the park's development. The PEC spent over $2 million in its campaign against Disney, including lobbying and public relations.

THE VOTE

On March 12, 1994, when the Virginia state legislature voted on a $163 million tax package for Disney, the results clearly favored Disney. This wasn't even a close call for the state government officials. Disney won 35 to 5 in the Virginia Senate and 73 to 25 in the House of Delegates. Things were looking up for the Disney's America project, although a new bumper sticker appeared in the Piedmont that said, "Gov. Allen Slipped Virginia a Mickey."

THE HISTORIANS AND JOURNALISTS TAKE OVER

Disney officials were elated after their victory in Richmond. It seemed likely that construction could begin in early 1995 after all. Meanwhile, Disney's opponents were not ready to give up the fight. Public debate on local issues such as traffic congestion and pollution had failed to keep Disney out of the Piedmont, and the anti-Disney crowd realized they needed to change the theme of their campaign. They needed a grander, more significant argument- something that would gain national attention.

The kernel of that argument had appeared in December 1993, in an editorial written to the Washington Post by Richard Moe, President of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and former Chief of Staff for Vice President Walter Mondale. In his article, Moe suggested that Disney's development would engulf "some of the most beautiful and historic countryside in America." He predicted that the park would reduce attendance at authentic northern Virginia historic landmarks, including the Manassas battlefield. Moe also questioned Disney's ability to seriously portray American history when the success of its other theme parks was based on simply showing visitors a good time.

Moe's article was followed by a similar piece published in mid-February 1994 by the Los Angeles Times , the newspaper serving Disney's southern California headquarters. This editorial was written by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nick Kotz, whose Virginia farm happened to be located three miles from the Disney site. Like Moe, Kotz based his article on the premise that Disney's park would desecrate land that should be considered a national treasure. He suggested that Disney would cheapen and trivialize its historic value. After the article was published, Kotz met with Moe over breakfast at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington to discuss anti-Disney strategy. This meeting was one of many that would follow among a growing network of the nation's most elite journalists and historians who were becoming increasingly concerned over Disney's plans.

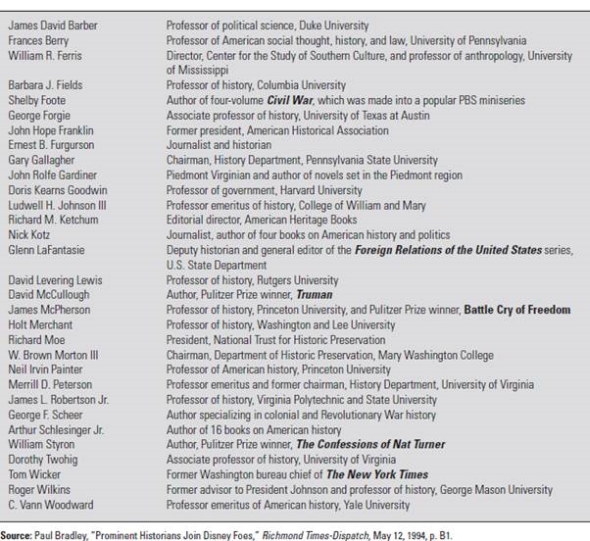

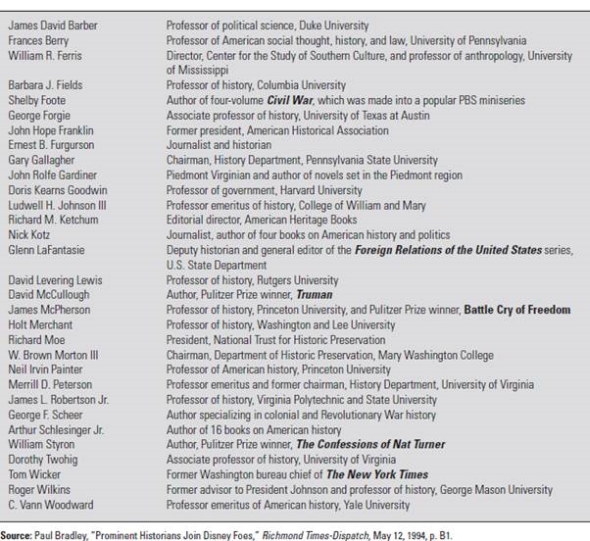

As the network grew, several prominent historians joined the fight against Disney and formed a group that became known as Protect Historic America. An early recruit was David McCullough, the author of several best-selling books, including a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Harry Truman. McCullough was very well known, particularly of late for his narration of the highly acclaimed Ken Burns "Civil War" series on PBS. Another prominent member was James McPherson, a Princeton University professor and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Battle Cry of Freedom. Exhibit 9.2 provides a list of many prominent authors and historians who joined Protect Historic America in its early stages.

By May, Protect Historic America was prepared to launch a national campaign in partnership with Moe's National Trust for Historic Preservation. Using funds donated by Piedmont residents, the group placed a fullpage ad in the May 2 edition of the Washington Post , asking Eisner to reconsider the Haymarket site. The ad included a tear-away response form at the bottom and generated over 5,000 responses. Nine days later, on May 11, the group held a news conference at the National Press Club that featured McCullough and Moe, among others. The prominent journalists in the group virtually assured that the conference would receive national news coverage.

During the well-publicized news conference, the speakers argued that Disney threat ened the Piedmont countryside, including historic towns and battlefields. The region's rich heritage made it valuable to all Americans. David McCullough stated, "We have so little left that's authentic and real. To replace what we have with plastic, contrived history is almost sacrilege."20 James McPherson, in a written statement presented to reporters, said, "A historical theme park in Northern Virginia, three miles from the Manassas National Battlefield, threatens to destroy the very historical landscape it purports to interpret."

The press conference, along with personal correspondence from McCullough and McPherson, convinced over 200 historians and writers to endorse the fight against Disney.

EXHIBIT 9.2 The Third Battle of Bull Run: The Disney's America Theme Park. Partial List of Historians and Authors in the Anti-Disney Campaign

Several historians wrote articles in national publications, attacking the Disney project. C. Vann Woodward, the noted Southern historian, wrote an article for the New Republic in which he stated:

What troubles us most is the desecration of a particular region... historians don't own history, but it isn't Disney's America either. Nor is it Virginia's. Every state... in the country sent sons to fight here for what they believed, right or wrong. They helped make it a national heritage, not a theme park.

The historians and journalists attempted to limit their arguments to the importance of preserving the Piedmont land and its historic heritage. Concerned that they would be regarded as cultural elitists, they tried to avoid the argument that Disney should not attempt to portray history in a theme park. There were several notable deviations from this strategy, however. McCullough once referred to Disney's plans as "McHistory." Shelby Foote, a Civil War historian, made it clear that he believed Disney would sentimentalize history as it had done to the animal kingdom.

Commentator George Will asked facetiously, "Is the idea to see your sister sold down the river, then get cotton candy?" Around this same time period, a lively online discussion took place on the H-Civwar listserve, whose members included academics and historians who were Civil War buffs.

DISNEY'S RESPONSE

Following the May 11 pres

When you wish upon a star, makes no difference who you are. Anything your heart desires will come to you. If your heart is in your dreams, no request is too extreme...

-Jiminy Cricket

On September 22, 1994, Michael Eisner, CEO of the Walt Disney Company, one of the most powerful and well-known media conglomerates in the world, stared out the window of his Burbank office, contemplating the current situation surrounding the Disney's America theme park. Ever since November 8, 1993, when The Wall Street Journal first broke the news that Disney was planning to build a theme park near Washington, D.C., ongoing national debate over the location and concept of the $650 million park had caused tremendous frustration. Eisner thought back over the events of the past year. How could his great idea have run into such formidable resistance?

THE CONTROVERSY COMES TO A HEAD

Eisner's secretary had clipped several newspaper articles covering two parades that took place on September 17. In Washington, D.C., several hundred Disney opponents from over 50 anti-Disney organizations had marched past the White House and rallied on the National Mall in protest of the park. On the same day in the streets of Haymarket, Virginia, near the proposed park site, Mickey Mouse and 101 localchildren dressed as Dalmatians had appeared in a parade that was filled with pro-Disney sentiment. Eisner was particularly struck by the contrast between the two pictures: one showing an anti-Disney display from the National Mall protest and another of Mickey and Minnie Mouse being driven through the streets of Haymarket during the exuberant community parade.

Despite the controversy depicted in the press, on September 21, Prince William County, Virginia, planning commissioners had recommended local zoning approval for Disney's America, and regional transportation officials had authorized $130 million in local roads to serve it. It appeared very likely that the project would win final zoning approval in October. At the state level, Virginia's Governor George Allen continued his strong support of the park's development.

Over the past three weeks, however, Eisner had been ruminating over a phone call he received in late August from John Cooke, President of the Disney Channel since 1985. Although Cooke had no responsibility for Disney's America, he had more experience in the Washington, D.C. political scene than any of Disney's other highest-ranking managers and was one of Eisner's most trusted executives. Cooke was not encouraging about the park's prospects. Quite familiar with many of the park's opponents, he believed they would not give up the fight under any circumstances. Given the anti-Disney coalition's considerable financial resources, the nationally publicized anti-Disney campaign could go on indefinitely, inflicting immeasurable damage on Disney's fun, family image. Cooke advised Eisner to think very seriously about ending the project.

Since the mid-1980s, Eisner's business strategy was to revitalize Disney by broadening its brand into new ventures. Although promising at first, now the wisdom of some of the ventures seemed less certain. The worst example, EuroDisney, the new Disney park located outside Paris, continued to flounder. The numbers for fiscal year 1994, due in just a couple of days on September 30, didn't look promising. Estimates said net income would be down to $300 million from $800 million the year before, mostly because EuroDisney lost $515 million from operations and $372 million from a related accounting charge.

The good news was that due to cost cutting, EuroDisney's losses were actually less than in the previous year, while the bad news was that attendance was also down. Prince al-Waleed bin Talal bin Adulaziz of Saudi Arabia had agreed to buy 24 percent of the park and build a convention center there, thus relieving some of the financial pressure, but it seemed that the negative press coverage of that park's troubles would never end.

The Disney's America problem was particularly bothersome, however. Eisner realized that the controversy surrounding the park, coupled with the many other highly publicized problems of 1994, was damaging Disney's image. Due to publicity about its highly visible corporate problems, Disney's image as a business threatened to tarnish its reputation for family-friendly fun and fantasy.

Personally, Eisner was particularly fond of the Disney's America concept. He had helped develop the original idea and had personally championed it within the Disney organization. He recalled the early meetings during which several Disney executives, including himself, had brainstormed an American history concept. He and the other executives had strongly believed that Disney had the unique capability of designing an American history theme park that would draw on the company's technical expertise and offer guests an entertaining, educational, and emotional journey through time. They envisioned guests, adults and children alike, embracing a park dedicated to telling the story of U.S. history. Eisner had hoped the park would be part of the personal legacy he would leave behind at Disney. As he told a Washington Post reporter, "This is the one idea I've heard that is, in corporate locker room talk, what's known as a no-brainer."

THE DISNEY'S AMERICA CONCEPT AND LOCATION

The idea of building an American history theme park originated in 1991 when Eisner and other Disney executives attended a meeting at Colonial Williamsburg in south eastern Virginia. The executives were impressed by the restored pre-Revolutionary capital. Disney had already been thinking about locations for theme parks that were on a somewhat smaller scale than the company's massive ones. Visiting Williamsburg helped Disney make the connection to a new park based on historical themes.

Disney's attention soon shifted focus to Washington, D.C. As the third-largest tourist market in the United States and the center of American government, the nation's capital seemed a natural location for an American history park. The abundance of historical sites in the area broadened its appeal as a center of American history. Disney's other parks were located on the fringes of developed urban centers (Anaheim, Orlando, Tokyo, and Paris). The parks gained advantages from their proximity to urban centers, but due to their peripheral locations, Disney was able to acquire lower-priced land and ensure a safe environment for visitors, far from inner-city congestion and crime.

Disney needed a location with easy access to an airport and an exit off an interstate highway. Executives hoped to find land that had already been zoned for development as well as local and state politicians who would be open to economic growth. In Prince William County, located in the heart of Virginia's Piedmont region, Disney found all these things. Dulles International Airport was located just east of Prince William County. U.S. Interstate 66 (I-66), the main traffic artery connecting Washington, D.C., with its western suburbs, could transport tourists straight from Washington's monuments and museums into Prince William County, a distance of about 35 miles.

The political and economic context also made Prince William County attractive to Disney. Virginia had long been a pro-growth state, and its governors were constantly under pressure to bring in new business. Democratic Governor Doug Wilder would leave office in November 1993, having lost some notable campaigns to bring growth to Virginia's economy. Polls showed that he would likely be replaced by Republican George Allen, the son of a former Washington Redskins American football coach and a graduate of the University of Virginia. If elected, Allen would be under instant pressure to create state economic growth. Most Prince William County officials were also "pro-growth," though not well prepared for it. The county's growing population of middle-class residents (up 62 percent since 1980) paid the highest taxes in the state of Virginia due to a dearth of economic development within the county. The Virginia legislature set an ambitious goal in 1990 to attract 14,000 jobs and $1 billion in nonresidential growth to the county to fund more and better schools and county administrative services, in addition to reducing residential taxes paid by each family.

In the spring of 1993, Peter Rummell, President of Disney Design and Development, which included the famous Imagineering group, as well as the real estate division, identified 3,000 acres in Prince William County near the small town of Haymarket (population 483). The largest property was a 2,300-acre plot of land, the Waverly Tract, owned by a real estate subsidiary of the Exxon Corporation. Waverly was already zoned for mixed-use development of homes and office buildings, yet due to a weak real estate market, Exxon had never broken ground on the undeveloped farmland. For a modest holding price, Exxon was willing to option the property. Using a scheme that had worked years before in Orlando, the Disney real estate group bought or put options on Waverly and the remaining 3,000 acres without revealing the company's corporate identity in any of the transactions.

THE VIRGINIA PIEDMONT

The northeast corner of Virginia comprises the Piedmont region. The region contains countless significant sites related to U.S. history, including, for example, the preserved homes of four of the first five U.S. presidents: Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. According to Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough, "This is the ground of our Founding Fathers. These are the landscapes-small towns, churches, fields, mountains, creeks, and rivers-that speak volumes."3 Thomas Jefferson loved the agrarian life he found on the farms east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. In his letters, he exulted over the region's "delicious spring," "soft genial temperatures," and good soil.

The region is also home to more than two-dozen Civil War battlefields. The U.S. Civil War was fought largely over the issue of slavery, pitting northern states against the southern states that had seceded from the union. Just a National Battlefield Park, land that is protected and preserved by the U.S. National Park Service, commemorating two major Civil War battles. The first battle in 1861 was the Civil War's first major land engagement. The second, in 1862, marked the beginning of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the North. On what would become some of the bloodiest soil in U.S. history, Lee reflected at Bull Run in 1861, "The views are so magnificent, the valleys so beautiful, the scenery so peaceful. What a glorious world the Almighty has given us. How thankless and ungrateful we are, and how we labor to mar His gifts."

Although largely rural and predominantly middle class, the region was also notable as home to some of America's most wealthy and influential citizens. The largest estates suggested the presence of privilege at every turn: perfect fences built from stone or wood, carefully manicured pastures, large barns requiring lots of hired help, a few private landing strips, and long private lanes lined with boxwood or dogwood that led to magnificent private homes. Exhibit 9.1 provides a map showing the locations of some of the area's most wealthy homeowners.

The Piedmont also had a history of successfully fighting local development projects. In the late 1970s, the Marriott Corporation had proposed building a large amusement park, and, in the late 1980s, a development group had planned to develop a major shopping mall in the area. Both projects were defeated by local opposition.

DISNEY'S PLANS REVEALED

To keep its land acquisition secret, Disney had done little to work with local government and communities, but by late October of 1993, Eisner learned that Disney's plans had begun to leak. It would only be a matter of days before the news would hit the media, so in the meantime Disney had to act quickly. Behind the scenes, Eisner contacted outgoing Governor Wilder and Governor-elect Allen. Both gave their immediate support and agreed to attend a public announcement scheduled for November 11. The company hired a local real estate law firm, and also retained the services of Jody Powell, former Press Secretary to President Jimmy Carter, who ran the Powell Tate public relations firm.

EXHIBIT 9.1 The Third Battle of Bull Run: The Disney's America Theme Park. Proximity of Disney's America Site to Several Wealthy Residents. Design: Bob Mansfield/Forbes

On November 8, 1993, a brief item appeared in The Wall Street Journal stating that Disney was planning to build a theme park somewhere in Virginia. That same day, Disney officials confirmed the story but provided no additional details. The next day, a Washington Post reporter identified Prince William County as the targeted area. Disney spokespeople confirmed the location and added some details. Disney officials briefed reporters and legislators, stating that they had investigated possible obstacles to the project, including environmental and historic preservation concerns, and believed there would be no serious problems. They also stated that they had studied traffic patterns on I-66 and believed additional theme park traffic would not exacerbate rush-hour congestion. Because 65 percent of Prince William County residents commuted to jobs in other northern Virginia counties, traffic congestion was a primary concern. On November 10, the Post ran the first full news story, headlined "Disney Plans Theme Park Here; Haymarket, VA: Project to Include Mall, Feature American History."

As local discussion increased, Disney held an upbeat news conference on November 11 and also issued a press release. Rummell, flanked by the governors and local officials, revealed an architectural model of the theme park and the surrounding development plans. The park logo featured a bold close-up of a stylized bald eagle rendered in navy blue, draped in red and white striped bunting, and with the words, "Disney Is America" emblazoned in gold across the eagle's chest.

Disney's America was presented as a "totally new concept... to celebrate those unique

American qualities that have been our country's strengths and that have made this nation the beacon of hope to people everywhere." Disney would draw upon its entertainment experience in multimedia and theme park attractions. Disney officials emphasized the park's focus on the Civil War. Guests would enter the park through a detailed Civil War-era village and then ride a steam train to explore nine areas, each devoted to an episode from American history. One of these included a Civil War fort, complete with battle reenactments. Other exhibits included "We the People," depicting the immigrant experience at Ellis Island, and "Enterprise," a factory town featuring a high-speed thrill attraction called "The Industrial Revolution."

Disney officials predominantly sold the park on its economic benefits to the local area, stating that the park would directly generate about 3,000 permanent jobs along with 16,000 jobs indirectly. Around the park, the company would develop resort hotels, an RV park, a 27-hole public golf course, a commercial complex with retail and office space, and 2,300 homes.11 Disney projected $169 million in tax revenues for the first 10 years after the park opened in 1998 and nearly $2 billion over its first 30 years. In addition, Disney would donate land for schools and a library and reserve up to 40 percent green space as a buffer around the core recreational area.

In part, the announcement came off better in print than at the conference. In the press release, Bob Weis, Senior Vice President of Walt Disney Imagineering, was quoted as saying, "Beyond the rides and attractions for which Disney is famous, the park will be a venue for people of all ages, especially the young, to debate and discuss the future of our nation and to learn more about its past by living it." In the conference, however, Weis said of the attractions, "We want to make you a Civil War soldier. We want to make you feel what it was like to be a slave, or what it was like to escape through the Underground Railroad." Weis's intended meaning was to refer to the new technology of virtual reality that would be used, but critics quickly jumped on the statement. Washington Post columnist Courtland Milloy contrasted the description to "authentic history" that would have to portray atrocities like slave whippings and rape.14 Author William Styron wrote that he believed the comment suggested that slavery was somehow a subject for fun or that the escape route used for slaves was similar to a subway system.

PIEDMONT OPPOSITION

Almost immediately after Disney confirmed its plans to build a park in Prince William County, anti-Disney forces began organizing their opposition. To many who were alarmed, the plans seemed already so well-developed that they gave the impression of a fait accompli. Just days after Disney's formal announcement, a meeting was held at the home of Charles S. Whitehouse, a retired foreign service officer who had owned property in the Virginia hunt country since the early 1960s. The dozen guests included William D. Rogers, former Undersecretary of State under Henry Kissinger and now a senior partner in a powerful Washington law firm; Joel McCleary, a former aide in the Carter White House and former Treasurer of the Democratic National Committee; and Lavinia Currier, great-granddaughter of Pittsburgh financier Andrew Mellon. William Backer, a former New York advertising executive who had created slogans for Coca Cola ("Coke- It's the Real Thing") and Miller Beer ("If you've got the time, we've got the beer"), also attended. The group worried that the proposed development would undermine the upper Piedmont's "traditional character and visual order."

The phrase came from the charter of the Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC), a rural-preservation group co-chaired by Whitehouse. Many of Whitehouse's guests had donated considerable amounts of time and money to the organization, which fought development and bought land and easements to preserve the area. The PEC was originally founded in 1927 by a group of prominent landowners. Over the years, it fought successfully against uranium mining and plans for a "western bypass" highway.

The group discussed the options for stopping Disney's encroachment upon the hunt country. There was the possibility of derailing the project during the Virginia legislature's next session. Rogers discussed some of the legal options. Backer suggested a negative publicity campaign, possibly at a national level, to force an image-conscious company like Disney to retreat. He argued for a subtle approach rather than a straight-on NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) campaign. He didn't want the opposition campaign to be viewed simply as a group of wealthy landowners who wanted to prevent a theme park from disturbing their fox hunting. As the meeting ended, Backer agreed to come up with a slogan.

A few days later, Backer presented his "Disney, Take a Second Look" slogan to the group. Backer's angle was to convince Disney that it should reassess the idea of building a theme park amid the beauty of the Piedmont. Although the campaign addressed Disney directly, it would remind anyone who saw it of the Piedmont's unspoiled and now-threatened natural beauty. Within a few days, the slogan was running in radio ads and incorporated on a letterhead. The logo accompanying the slogan showed a balloon, with a barn and farmhouse inside, drifting away in the breeze.

This initial meeting was followed by dozens of others in the coming weeks and months. One week after the gathering at the Whitehouse home, over 500 people attended a meeting at the Grace Episcopal Church in The Plains, Virginia, about seven miles west of the Disney site. The meeting's attendants represented a wide range of economic backgrounds, but they were united in their preference for the rural life they enjoyed.

Megan Gallagher, Whitehouse's Co- Chairman of the Piedmont Environmental ?Council, led the meeting, reminding the group of other local protest movements that had stopped big projects. Other speeches rounded out the audience's concerns: the park's estimated 9 million annual visitors would spark low-density ancillary development like that around Anaheim and Orlando. The pristine countryside would be overcome by cheap hotels, restaurants, and strip malls. Already problematic traffic congestion would be exacerbated. The park would create low-wage jobs and not provide the tax base that the Disney plan promised. During the meeting, the Piedmont Environmental Council, which had already committed $100,000 of its $700,000 annual budget to the project, emerged as the leading opposition group.

A few days after the meeting at Grace Episcopal Church, another meeting organized by the Prince Charitable Trusts of Chicago, another land preservation group, was held at a local restaurant. This meeting brought together several regional and national environmental groups concerned about the Disney's America project. Eventually, the Prince Charitable Trusts would give over $400,000 to 14 different anti-Disney groups that conducted studies, gave press conferences, and attacked Disney from every possible environmental angle. The largest grant went to the National Growth Management League, which mounted a local advertising campaign under the name "Citizens Against Gridlock." The campaign depicted I-66, already one of northern Virginia's busiest and congested highways, as "Disney's parking lot."

In early December, the PEC held a news conference in a Washington hotel to increase the reach of its "Second Look" campaign. It retained a prominent Washington law firm as well as a public relations firm. The group began recruiting and organizing dozens of volunteers. It sent out a fundraising letter seeking $500,000 in contributions. It also commissioned experts to assess the park's impact on the environment, urban sprawl, traffic, employment, and property taxes.

DISNEY'S CAMPAIGN

Soon after the public announcement, Disney undertook concerted efforts to win over state and local government, as well as constituencies within proximity of the proposed site. Virginia's new Governor, George Allen, immediately promoted the Disney project. He believed Disney's worldwide reputation would make Virginia an international tourist destination, bringing millions of travelers to the state. In numerous press releases, Allen endorsed Disney's belief that the project would create 19,000 jobs and bring millions of new tax dollars to state and municipal coffers.

By early January, Disney asked the state to bear some of the costs of the new park. Disney requested $137 million in state highway improvements and $21 million to train workers, move equipment from Orlando, pay for advertising, and put up highway signs directing tourists to the park. These funds would have to be guaranteed by the end of the current state legislative session to allow Disney to move ahead with development in early 1995. Now focusing on Virginia's state capital, Disney retained a well-connected Richmond law firm to handle its lobbying efforts. It also hired a Richmond event-planning firm to organize two large receptions. Lobbying expenses alone reached almost $450,000, including $32,000 for receptions and $230 for the Mickey Mouse ties given to state legislators.

Allen supported Disney's request and argued the highway improvements Disney planned would ease traffic problems that already existed in northern Virginia, in addition to accommodating the extra traffic generated by the park. The state's support of the project, he said, would send a message that Virginia was "open for business."

Disney officials met with African-American legislators and promised to ensure that minorities got a good shot at contracts and jobs. They invited a dozen officials from area museums and historic sites, including Monticello and Colonial Williamsburg, to a meeting in Orlando to discuss their plans for portraying history in the northern Virginia park. In Richmond, Disney lobbyists portrayed opponents as wealthy landowners who simply did not want Disney in their backyards.

Disney sought and received strong support from the Prince William business community, especially realtors, contractors, hotels, restaurants, and utility companies. The Disney staff also poured tremendous effort into harnessing the support of local citizens, spending hours preaching the message of neighborliness to local groups. Groups formed to support the park, including the Welcome Disney Committee, Friends of the Mouse, Youth for Disney, and Patriots for Disney. Members of these groups attended state legislative hearings, gave testimony, and handed out bumper stickers and buttons. Disney sent newsletters to 100,000 local households and retained a second Washington public relations firm to handle grassroots support.

Disney also entered negotiations with the National Park Service at the Manassas park, which was three miles away. The company agreed to limit the height of its structures to 140 feet so they would not be visible from the park and to develop a special transit bus system that would transport 20 percent of Disney guests and 10 percent of employees. The company promised to promote historic preservation and the Manassas National Battlefield Park within Disney's America and immediately donated money to an allied nonprofit group.

THE PEC'S CAMPAIGN

The PEC mounted a strong effort in Richmond as well, including hiring two full-time lobbyists. Its campaign was based on the premise that the park was a bad business deal for Virginia. The PEC claimed that the park would generate fewer jobs than Disney and Governor Allen had promised-6,300 rather than 19,000- and that the jobs would not pay well. They accused Allen of exaggerating the tax benefits. They emphasized the traffic and air pollution that would be caused by the park. They also suggested 32 other sites in the Washington area that would be more suited to the project than the current site. Finally, they suggested that the state should not have to fund any of the park's development. The PEC spent over $2 million in its campaign against Disney, including lobbying and public relations.

THE VOTE

On March 12, 1994, when the Virginia state legislature voted on a $163 million tax package for Disney, the results clearly favored Disney. This wasn't even a close call for the state government officials. Disney won 35 to 5 in the Virginia Senate and 73 to 25 in the House of Delegates. Things were looking up for the Disney's America project, although a new bumper sticker appeared in the Piedmont that said, "Gov. Allen Slipped Virginia a Mickey."

THE HISTORIANS AND JOURNALISTS TAKE OVER

Disney officials were elated after their victory in Richmond. It seemed likely that construction could begin in early 1995 after all. Meanwhile, Disney's opponents were not ready to give up the fight. Public debate on local issues such as traffic congestion and pollution had failed to keep Disney out of the Piedmont, and the anti-Disney crowd realized they needed to change the theme of their campaign. They needed a grander, more significant argument- something that would gain national attention.

The kernel of that argument had appeared in December 1993, in an editorial written to the Washington Post by Richard Moe, President of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and former Chief of Staff for Vice President Walter Mondale. In his article, Moe suggested that Disney's development would engulf "some of the most beautiful and historic countryside in America." He predicted that the park would reduce attendance at authentic northern Virginia historic landmarks, including the Manassas battlefield. Moe also questioned Disney's ability to seriously portray American history when the success of its other theme parks was based on simply showing visitors a good time.

Moe's article was followed by a similar piece published in mid-February 1994 by the Los Angeles Times , the newspaper serving Disney's southern California headquarters. This editorial was written by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nick Kotz, whose Virginia farm happened to be located three miles from the Disney site. Like Moe, Kotz based his article on the premise that Disney's park would desecrate land that should be considered a national treasure. He suggested that Disney would cheapen and trivialize its historic value. After the article was published, Kotz met with Moe over breakfast at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington to discuss anti-Disney strategy. This meeting was one of many that would follow among a growing network of the nation's most elite journalists and historians who were becoming increasingly concerned over Disney's plans.

As the network grew, several prominent historians joined the fight against Disney and formed a group that became known as Protect Historic America. An early recruit was David McCullough, the author of several best-selling books, including a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Harry Truman. McCullough was very well known, particularly of late for his narration of the highly acclaimed Ken Burns "Civil War" series on PBS. Another prominent member was James McPherson, a Princeton University professor and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Battle Cry of Freedom. Exhibit 9.2 provides a list of many prominent authors and historians who joined Protect Historic America in its early stages.

By May, Protect Historic America was prepared to launch a national campaign in partnership with Moe's National Trust for Historic Preservation. Using funds donated by Piedmont residents, the group placed a fullpage ad in the May 2 edition of the Washington Post , asking Eisner to reconsider the Haymarket site. The ad included a tear-away response form at the bottom and generated over 5,000 responses. Nine days later, on May 11, the group held a news conference at the National Press Club that featured McCullough and Moe, among others. The prominent journalists in the group virtually assured that the conference would receive national news coverage.

During the well-publicized news conference, the speakers argued that Disney threat ened the Piedmont countryside, including historic towns and battlefields. The region's rich heritage made it valuable to all Americans. David McCullough stated, "We have so little left that's authentic and real. To replace what we have with plastic, contrived history is almost sacrilege."20 James McPherson, in a written statement presented to reporters, said, "A historical theme park in Northern Virginia, three miles from the Manassas National Battlefield, threatens to destroy the very historical landscape it purports to interpret."

The press conference, along with personal correspondence from McCullough and McPherson, convinced over 200 historians and writers to endorse the fight against Disney.

EXHIBIT 9.2 The Third Battle of Bull Run: The Disney's America Theme Park. Partial List of Historians and Authors in the Anti-Disney Campaign

Several historians wrote articles in national publications, attacking the Disney project. C. Vann Woodward, the noted Southern historian, wrote an article for the New Republic in which he stated:

What troubles us most is the desecration of a particular region... historians don't own history, but it isn't Disney's America either. Nor is it Virginia's. Every state... in the country sent sons to fight here for what they believed, right or wrong. They helped make it a national heritage, not a theme park.

The historians and journalists attempted to limit their arguments to the importance of preserving the Piedmont land and its historic heritage. Concerned that they would be regarded as cultural elitists, they tried to avoid the argument that Disney should not attempt to portray history in a theme park. There were several notable deviations from this strategy, however. McCullough once referred to Disney's plans as "McHistory." Shelby Foote, a Civil War historian, made it clear that he believed Disney would sentimentalize history as it had done to the animal kingdom.

Commentator George Will asked facetiously, "Is the idea to see your sister sold down the river, then get cotton candy?" Around this same time period, a lively online discussion took place on the H-Civwar listserve, whose members included academics and historians who were Civil War buffs.

DISNEY'S RESPONSE

Following the May 11 pres

Explanation

DN is a national theme and amusement par...

Corporate Communication 6th Edition by Paul Argenti

Why don’t you like this exercise?

Other Minimum 8 character and maximum 255 character

Character 255